Bacterial Peritonitis among Chronic Liver Disease Patients - A Cross-sectional Study from Northeast India

JASPI March 2024/ Volume 2/Issue 1

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Tiewsoh I, Mitra A, Lynrah KG, et al.Bacterial Peritonitis among Chronic Liver Disease Patients – A Cross-sectional Study from Northeast India. JASPI. 2024;2(1):5-10 DOI: 10.62541/jaspi006

ABSTRACT

Background: In the present era of increasing antimicrobial resistance in multiple infections, many studies have shown that even with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), the bacteriological and resistance patterns have changed over the years with regional variations. This study was conducted to determine the bacteriological profile of peritonitis patients among the group of cirrhotic patients and their outcomes.

Methodology: This was a one-year cross-sectional observational study in which cirrhotic patients with ascites were evaluated for SBP. Cytological analysis, biochemical tests (albumin, protein, glucose, lactate dehydrogenase), and culture and sensitivity on the ascitic fluid were carried out.

Results: 120 cirrhotic patients with ascites were included in the study. Thirty-eight (31.99%) patients had SBP. Classical SBP was present in 13 patients (34.21%), bacterascites in 7 patients (18.42%) and culture-negative neutrocytic ascites (CNNA) in 18 patients (47.36%). Escherichia coli was the most common organism (50%, n=10), followed by Acinetobacter spp. (15%, n=3), Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp. and Enterococcus spp. (10%, n=2 each), and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) (5%, n=1). The mortality among the SBP patients was higher than that among the non-SBP patients (42.10% vs. 15.85%, p=0.0013). Sepsis (with or without septic shock) and renal failure were the most common causes of mortality in these SBP patients.

Conclusion: The present study showed that culture-positive SBP in cirrhotic patients was mainly attributed to gram-negative bacterial infections. The resistance among common bacterial isolates was high against third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones. Patients with multidrug-resistant infections had poor outcomes.

KEYWORDS: Antimicrobial resistance; culture-negative neutrocytic ascites; liver cirrhosis; multidrug-resistant infections; Peritonitis

INTRODUCTION

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is a life-threatening infection with a significant impact on short-term mortality in patients with chronic liver disease (CLD). Therefore, it requires prompt recognition and treatment.1 The development of SBP in advanced cirrhosis is an indication for liver transplantation.2 Third-generation cephalosporins, mainly cefotaxime, are recommended as the first-line antibiotic for treating SBP.3 However, due to the irrational use of antibiotics, which is evident in the human medical field and poultry, there has been an increased incidence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) infections in humans that were not apparent in the previous century. There is an increase in extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing gram-negative bacteria and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), which pose a new challenge in treating SBP.1,4

As MDR is directly related to the mortality of patients, the only factors modifiable in the present condition are a timely diagnosis and effective first-line treatment. With many antibiotic-resistant strains in the current era, the local antibiogram is a must, as it will guide choosing the best empirical antibiotic therapy at the right time to prevent higher mortality.

Considering all these factors and with the limited data in Northeast India, the investigators carried out this study to determine the burden of peritonitis patients with decompensated CLD and the bacteriological profile, clinical spectrum, associated diseases, and complications among both SBP and non-SBP patients.

METHODOLOGY

Study design and center

It was a cross-sectional observational study of one-year duration conducted in North Eastern Indira Gandhi Regional Institute of Health and Medical Sciences, a tertiary care referral hospital in Shillong, Meghalaya, India.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Patients with CLD and ascites were included and evaluated for SBP. Patients who had antibiotic therapy before admission and those with ascites due to other causes were excluded.

Laboratory investigations

Ascitic fluid samples were aseptically collected from patients by ascitic tap (diagnostic paracentesis) from the patient’s abdomen. Cytological analysis, biochemical tests (albumin, protein, glucose, lactate dehydrogenase), and culture and sensitivity on the ascitic fluid were carried out per standard guidelines. The bacteriological profile of the ascitic fluid culture and the respective antibiotic sensitivity of the bacterial isolates were analyzed.

Definitions and outcome variables

SBP was defined if the ascitic fluid sent for analysis had ≥250 polymorphonuclear (PMN) cells/mm3 or if the ascitic fluid bacterial culture was positive without an intra-abdominal source of infection or a malignancy.3 The outcome of the patients and response to antibiotic therapy were assessed in terms of resolution, defined as the disappearance of clinical signs of infection and >25% decrease in the ascitic fluid neutrophil count of the initial value when repeated after 48 hrs.

Statistical analysis

The data were entered in Microsoft Excel 2016. SPSS version 26 was used to perform the statistical analysis. Categorical variables are displayed as percentages, and continuous variables are expressed as the mean and median. A comparative study using the Chi-square test was performed for categorical variables, and the Student’s t-test was used to compare continuous variables between the patients with SBP and those without SBP. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Ethical statement

The study was approved by the Institute Ethical Committee of North Eastern Indira Gandhi Regional Institute of Health and Medical Sciences, Shillong, Meghalaya (Ref: T11/17/11 IEC NEIGRIHMS). Written informed consent was collected from all patients before their inclusion in the study.

RESULTS

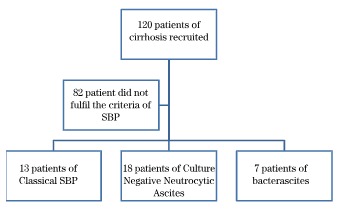

A total of 120 cirrhotic patients with ascites were included in the study. SBP was detected in 38 patients (31.99%) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: STROBE flow chart

Classical SBP was present in 13 patients, bacterascites SBP in 7 patients and culture-negative neutrocytic ascites (CNNA) in 18 patients.

Table 1. Demographic profile and laboratory parameters of the SBP and non-SBP patients | ||||

Total (N= 120) | Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (n=38) | Non-spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (n=82) | p-value | |

Age (mean) | 45.59 ± 10.98 | 45.81±13.19 | 45.48±9.87 | |

Sex | ||||

Male | 96 (80%) | 28(78%) | 68(82%) | |

Female | 24 (20%) | 10(26%) | 14(36%) | |

Causes of liver cirrhosis | ||||

Alcohol consumption | 91(75.80%) | 28(78%) | 63(76%) | 0.715 |

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | 5(4.16%) | 1(2%) | 4(4%) | 0.557 |

Hepatitis B | 2(1.66%) | 1(2%) | 1(1%) | 0.534 |

Hepatitis C | 3(2.50%) | 0 | 3(3%) | 0.233 |

Drug-induced | 2(1.66%) | 2(5%) | 0 | 0.029 |

Hepatitis B and alcohol | 3(2.50%) | 1(2%) | 2(2%) | 0.002 |

Hepatitis C and alcohol | 1(0.83%) | 0 | 1(1%) | 0.511 |

Idiopathic | 13(10.83%) | 5(13%) | 8(9%) | 0.569 |

Child-Pugh Score | ||||

A | 0 | 0 | ||

B | 36 (30%) | 10 (26%) | 26(31%) | |

C | 84 (70%) | 28 (73%) | 56(68%) | |

Clinical presentation | ||||

Abdominal tenderness | 31 | 26(68.42%) | 5(6.09%) | <0.001 |

Jaundice | 76 | 25(65.78%) | 51(62.19%) | 0.7 |

Pain abdomen | 37 | 17(44.73%) | 20(24.39%) | 0.024 |

Fever | 23 | 16(42.10%) | 17(20.73%) | 0.014 |

Hepatic Encephalopathy | 37 | 13(34.21%) | 24(29.26%) | 0.581 |

Shortness of breath | 66 | 11(28.94%) | 51(62.19%) | 0.001 |

UGI Bleeding | 22 | 11(28.94%) | 11(13.41%) | 0.041 |

Vomiting | 16 | 5(13.15%) | 11(13.41%) | 0.954 |

Constipation | 19 | 4(10.52%) | 15(18.29%) | 0.282 |

Diarrhoea | 4 | 1(2.63%) | 3(3.65%) | 0.746 |

Laboratory parameters | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | p-value | |

Haemoglobin(gm/dl) | 9.46 (2.76) | 8.79(2.17) | 0.1525 | |

Total leucocyte counts | 17572.63 (25757.35) | 10914.63 (7948.17) | 0.0344 | |

Platelets | 168815.8 (67529.32) | 199573.2 (196367.4) | 0.35 | |

INR | 1.99 (0.91) | 1.86 (0.63) | 0.3657 | |

Total Bilirubin (mg/dl) | 8.24 (9.4) | 6.49 (7.29) | 0.2679 | |

Aspartate aminotransferase(U/l) | 78.94 (54.7) | 84.95 (59.26) | 0.5976 | |

Alanine transaminase(U/l) | 52.8 (36.59) | 62.26 (79.31) | 0.4879 | |

Serum albumin (mg/dl) | 2.39 (0.62) | 2.38 (0.55) | 0.9293 | |

Urea (mg/dl) | 77.08 (66.9) | 48.81 (47.8) | 0.0093 | |

Creatinine (mg/dl) | 2.05 (1.53) | 1.67 (1.66) | 0.2345 | |

Sodium (mmol/dl) | 137.96 (4.74) | 136.49 (16.38) | 0.5890 | |

Potassium (mmol/dl) | 4.26 (0.82) | 4.08 (0.78) | 0.2496 | |

Ascitic fluid analysis | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

Total count | 1701.31(1651.37) | 192.13(255.37) | <0.0001 | |

Glucose | 112.76(39.16) | 130.72(37.28) | 0.0172 | |

Total Protein | 1.31(0.9) | 1.23(0.9) | 0.6514 | |

Albumin | 0.47(0.44) | 0.42(0.45) | 0.5697 | |

SAAG | 1.93(0.55) | 1.97(0.44) | 0.6701 | |

Descriptive characteristics

The demographic profile and laboratory parameters of all patients are depicted in Table 1.

80% of all participants were males. Consumption of alcohol was the predisposing factor of cirrhosis in the majority (75.80%) of cases. Most patients in the present

study group fell under CHILD-PUGH class C (70%), followed by class B (30%). Abdominal tenderness (68.42%), jaundice (65.78%), and abdominal pain (44.73%) were the common presentations of patients with SBP, whereas non-SBP patients presented mostly with jaundice (62.19%), and shortness of breath (62.19%).

Comparative analysis between SBP and non-SBP groups of patients

There were no statistically significant differences with respect to gender, causes of liver cirrhosis (except for drug-induced and combined hepatitis B and alcohol consumption), Child-Pugh Score, jaundice, hepatic encephalopathy, vomiting, abdominal pain, fever, constipation, and diarrhea between the SBP and non –SBP groups except for the presence of abdominal tenderness and shortness of breath in the SBP group.

The mean values of the total leucocyte count and urea were significantly higher in the SBP group than in the non-SBP group. Although not significant, serum creatinine was also higher among the SBP group than the non-SBP group.

Bacteriological and susceptibility profile

Out of the 20 culture-positive cases of SBP (13 classical SBP and seven bacterascites), the majority could be attributed to Gram-negative bacterial infections (n=17; 85%), whereas Gram-positive bacterial infections contributed only 15% (n=3) of the culture-positive SBP cases. E. coli was the most common organism (n=10, 50%), followed by Acinetobacter spp. (n=3, 15%), K. pneumoniae, Enterobacter spp., Enterococcus spp. (n=2, 10% each) and methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) (n=1, 5%), respectively.

The susceptibility profile of the Gram-negative isolates varied across species. E. coli isolates (n=10) were mostly resistant to cefotaxime (80%) and ciprofloxacin (60%), followed by piperacillin-tazobactam (40%) and meropenem (40%), respectively. The second most common isolate, Acinetobacter spp (n=3), was totally resistant to third-generation cephalosporin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and meropenem.

On the other hand, all Gram-positive isolates (Enterococcus spp.=2 and MSSA=1) were susceptible to linezolid (100%), vancomycin (100%), and gentamicin (100%). Both isolates of enterococci were resistant to ciprofloxacin.

Overall, 60% of all bacterial isolates were resistant to at least one antibiotic in three or more antibiotic classes and were classified as multidrug-resistant (MDR).

The outcome of patients

Out of 38 SBP patients, 16 (43.10%) expired. The mortality among the SBP patients (42.10%) was significantly higher than that among the non-SBP patients (15.85%). Among the 16 SBP patients who expired, sepsis and renal failure were the most common causes of mortality (6; 37.50% each), whereas two patients (12.50%) died due to upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Aspiration pneumonia and hepatic encephalopathy were responsible for the death of one patient (6.25%) each. The culture-negative SBP patients had a poorer prognosis in terms of mortality than the culture-positive patients (44.44% vs. 40%), but the difference was not statistically significant. Moreover, cases with MDR bacterial infections had a higher mortality rate than those with non-MDR bacterial infections (41.66% vs. 37.5%).

DISCUSSION

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP) is a severe complication of cirrhosis, and its treatment involves the use of antibiotics and the prophylactic use of fluoroquinolones. Antimicrobial resistance has emerged as one of the most critical health issues in the 21st century. A systematic review recently revealed that the global burden of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) was 4.95 million deaths in 2019, and 1.27 million of these deaths were from bacterial AMR.5 A risk of AMR development in cirrhotic patients was previously attributed to antibiotic prophylaxis with fluoroquinolones;6 however, a randomized control trial by Moreau et al. on 291 cirrhotic patients found that prophylactic antibiotic therapy was not associated with an increased incidence of MDR infections.7

In the present study, the ascitic fluid culture was positive in 52.63% of the SBP-diagnosed cases. In a recent study by Ding et al. on 748 patients with SBP, 44.7% had culture-positive SBP.1 Other studies have shown that culture positivity may range from 35% to as high as 65% .8,9

In the current study, gram-negative organisms were isolated in 85% of the culture-positive SBP cases, with E. coli being the most common organism (50%). This finding is similar a retrospective cohort study on 236 patients with SBP by Cheong et al. where 72.9% of SBP cases were due to gram-negative bacteria and 43.2% were due to E. coli.10 This is consistent with a recent review by Wang et al. on gut microbiota and bacterial translocation, showing that gram-negative organisms are predominant.11 Few studies reported gram-positive bacteria as the predominant cause of SBP.12-15 But the present study did not support the latter finding, with Enterococcus spp and MSSA contributing to only 15% of all culture-positive SBP cases.

This study found a high proportion of MDR organisms (60%) in culture-positive SBP cases. A recent retrospective study by Olivera et al. on 113 monobacterial SBP cases found MDR bacteria in 46.9% of cases.16 The present study found that E. coli was the most common among the gram-negative isolates, with 80% isolates resistant to third-generation cephalosporins and 60% isolates resistant to fluoroquinolones. Previous studies have shown that cephalosporin resistance was 16-25%, and quinolone resistance was seen in 25.7%-70% of the isolates.16-19 These findings of this study are worrisome since third-generation cephalosporins are the drug of choice for treating SBP, and fluoroquinolones are used as prophylactic medication.

Cases with MDR bacterial infections had a higher mortality rate compared to cases with non-MDR bacterial infections (41.66% vs. 37.5%). Similar results were also obtained in a Spanish study by Fernandez et al., who showed that developing infections by resistant bacteria is associated with higher mortality rates.20 Merli et al. also mentioned in their research that the hospital mortality rate related to drug-resistant organisms was twice as high as that associated with other organisms.21

There were a few limitations in the present study. The present study had a small sample size, and included only 38 SBP cases. The study was conducted in a single tertiary care hospital. Future multi-centric studies with more participants may be planned based on the findings of the present study.

CONCLUSION

The present study showed that culture-positive SBP in cirrhotic patients was mainly attributed to Gram-negative bacterial infections, particularly E. coli. The resistance among common bacterial isolates was high against third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones. Patients with MDR infections had poor outcomes. Thus, in the present era of AMR, the local antibiogram is critical in dictating empirical therapy for patients with SBP, and there is a need for good antibiotic stewardship in all hospital settings.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

None

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

IT: Gave Concept

AM: Design

KGL: Collected data

PKB: Analysed

CJL: Review & editing; Supervision; Validation

GRBT: Review & editing; Supervision; Validation

ML: Review & editing; Supervision; Validation

GW: Reviewed the draft with final approval of article

REFERENCES

Ding X, Yu Y, Chen M, Wang C, Kang Y, Lou J. Causative agents and outcome of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: community-acquired versus nosocomial infections. BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19(1):463.

Nobre SR, Cabral JE, Gomes JJ, Leitão MC. In-hospital mortality in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a new predictive model. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;20(12):1176-81.

Wiest R, Krag A, Gerbes A. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: recent guidelines and beyond [published correction appears in Gut. 2012 Apr;61(4):636]. Gut. 2012;61(2):297-310.

Alaniz C, Regal RE. Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: a review of treatment options. P T. 2009;34(4):204-10.

Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629-55.

Fernández J, Navasa M, Gómez J, et al. Bacterial infections in cirrhosis: epidemiological changes with invasive procedures and norfloxacin prophylaxis. Hepatology. 2002;35(1):140-8.

Moreau R, Elkrief L, Bureau C, et al. Effects of Long-term Norfloxacin Therapy in Patients With Advanced Cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(6):1816-1827.e9.

Ison MG. Empiric treatment of nosocomial spontaneous bacterial peritonitis: One size does not fit all. Hepatology. 2016;63(4):1083-5.

Pericleous M, Sarnowski A, Moore A, Fijten R, Zaman M. The clinical management of abdominal ascites, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis and hepatorenal syndrome: a review of current guidelines and recommendations. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28(3):e10-e18.

Cheong HS, Kang CI, Lee JA, et al. Clinical significance and outcome of nosocomial acquisition of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in patients with liver cirrhosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(9):1230-6.

Wang C, Li Q, Ren J. Microbiota-Immune Interaction in the Pathogenesis of Gut-Derived Infection. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1873.

Kim JH, Jeon YD, Jung IY, et al. Predictive Factors of Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis Caused by Gram-Positive Bacteria in Patients With Cirrhosis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95(17):e3489.

Cholongitas E, Papatheodoridis GV, Lahanas A, Xanthaki A, Kontou-Kastellanou C, Archimandritis AJ. Increasing frequency of Gram-positive bacteria in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver Int. 2005;25(1):57-61.

Alexopoulou A, Papadopoulos N, Eliopoulos DG, et al. Increasing frequency of gram-positive cocci and gram-negative multidrug-resistant bacteria in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver Int. 2013;33(7):975-81.

Fernández J, Acevedo J, Castro M, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of infections by multiresistant bacteria in cirrhosis: a prospective study. Hepatology. 2012;55(5):1551-61.

Oliveira JC, Carrera E, Petry RC, et al. High Prevalence of Multidrug Resistant Bacteria in Cirrhotic Patients with Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis: Is It Time to Change the Standard Antimicrobial Approach?. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;2019:6963910.

Sarwar S, Tarique S, Waris U, Khan AA. Cephalosporin resistance in community-acquired spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Pak J Med Sci. 2019;35(1):4-9.

Ardolino E, Wang SS, Patwardhan VR. Evidence of Significant Ceftriaxone and Quinolone Resistance in Cirrhotics with Spontaneous Bacterial Peritonitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(8):2359-67.

Shizuma T. Spontaneous bacterial and fungal peritonitis in patients with liver cirrhosis: A literature review. World J Hepatol. 2018;10(2):254-66.

Fernández J, Prado V, Trebicka J, et al. Multidrug-resistant bacterial infections in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and with acute-on-chronic liver failure in Europe. J Hepatol. 2019;70(3):398-411.

Merli M, Lucidi C, Di Gregorio V, et al. An empirical broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy in health-care-associated infections improves survival in patients with cirrhosis: A randomized

Submit a Manuscript:

Copyright © Author(s) 2024. JASPI- Journal of Antimicrobial Stewardship Practices and Infectious Diseases.