Global Preparedness for Clinical Research in Emerging Infections: Lessons from ISARIC's Data-Driven Covid-19 Response

JASPI June 2025 / Volume 3 /Issue 2

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Gallo EG, Edinburgh T, Vallejo SD et al.Global Preparedness for Clinical Research in Emerging Infections: Lessons from Isaric’s Data-Driven Covid-19 Response. JASPI. 2025;3(2): 1-4 DOI: 10.62541/jaspi082

INTRODUCTION

Effective outbreak response relies on timely, high-quality data to guide clinical care and public health action. Such data help detect transmission patterns, prioritise interventions, and allocate resources efficiently. However, collecting structured, interoperable, and actionable data in outbreak settings is challenging, especially under pressure and with limited resources. To be useful, data must be adaptable to local needs and standardised to support rapid decision-making, a balance that poses both technical and logistical challenges.

With this in mind, the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infection Consortium (ISARIC)1 has worked over the last 14 years to provide a global, coordinated, and agile research response to outbreaks. The consortium has expanded into a federation of 70 member networks across 133 countries, with hubs in Manila, Karachi, Accra, Rio de Janeiro, Chía, Dhaka and Banjul. ISARIC’s mission is to generate and disseminate clinical research evidence whenever and wherever infectious disease outbreaks occur.

A defining feature of ISARIC’s work is pandemic preparedness. Since 2012, ISARIC has championed a coordinated global approach to emerging infectious diseases research response2. ISARIC has developed and disseminated standardised protocols and case report forms (CRFs) that can be rapidly activated in response to emerging outbreaks. Databases, study document templates, and study implementation support were provided to enable the rapid implementation of these tools. A cornerstone of these catalysts is the Clinical Characterisation Protocol (CCP)3. CCP is a flexible research protocol designed to capture the key clinical questions about acute illness from emerging pathogens. It is intentionally broad, allowing for rapid customisation and ethics approvals before outbreaks begin.

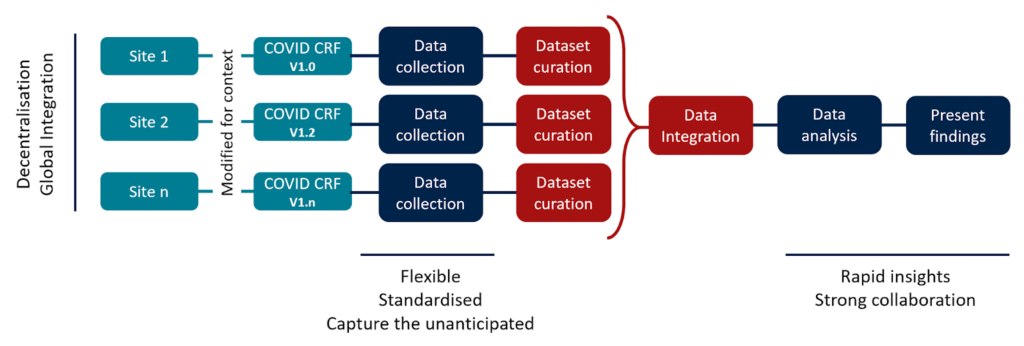

Since 2012, the CCP has been activated for various infectious diseases, including Ebola, MERS-CoV, Zika, Severe Acute Respiratory infections (SARI), plague, COVID-19, Nipah, Mpox, dengue and yellow fever. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it was implemented across 83 countries, often with site-specific modifications. While this flexibility was crucial for local relevance, it later introduced substantial heterogeneity that complicated data integration and analysis.6

The magnitude of the COVID-19 pandemic required a demanding response for many reasons. In the data context, it exposed the hidden labour of dataset curation. Although data collection initially followed a uniform CRF template, sites quickly modified it to suit their specific clinical contexts and research questions, leading to multiple CRF versions and variable structures. Reconciling these into a analysable dataset demanded extensive curation efforts.

Dataset curation tasks included quality checks and cleaning, anonymising sensitive fields, creating variable dictionaries, standardising to a common schema, and mapping free-text responses to controlled vocabularies. Data quality was ensured through validation against expected biological and temporal ranges, internal consistency checks, analysis of missing data and outliers, and follow-up queries with collection sites for clarification. These steps consumed far more time than initially anticipated. Free-text fields proved challenging for two reasons. First, direct identifiers were removed, and additional steps were taken to ensure that all indirect identifiers were either masked or eliminated to protect privacy. Second, the text had to be interpreted and clustered into meaningful categories. For example, some symptom-related terms such as “loss of taste”, “ageusia”, and “impaired taste”, could initially only be entered as free text. Emerging patterns of such symptoms needed to be identified and harmonised under a single concept and then included as new variables in subsequent iterations of the CRF. Another technically demanding aspect of data curation was the integration of multiple datasets across sites with divergent coding systems and options, into a single consistent data schema. However, the result of this effort was highly impactful: the resulting ISARIC COVID-19 dataset4, comprising detailed clinical data from nearly a million hospitalised patients, supported the generation of high-quality clinical research evidence through numerous manuscripts and reports led by clinical researchers around the world.

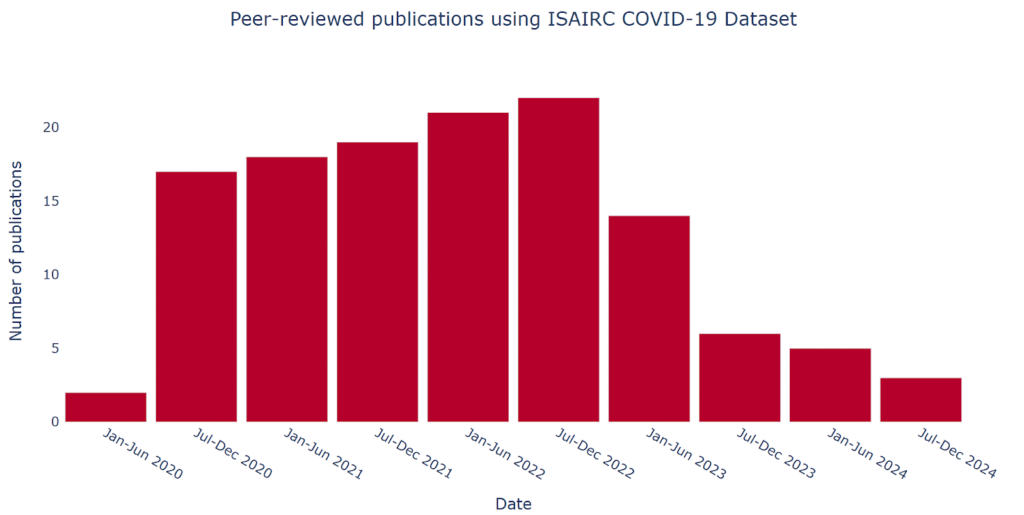

The dataset was built from voluntary contributions by health and research institutions motivated to accelerate the generation of globally comparable, patient-centric evidence and maximise the impact of their data collection efforts. ISARIC shared standard templates for research ethics applications and data sharing agreements to support robust governance processes at each contributing institution. The strong data security and privacy protection framework developed by ISARIC over the preceding decade was key to securing the participation of institutions based in nations with strict data sharing requirements. An additional driver of collaboration was the ability for staff from contributing institutions to access the data of other contributors to lead collaborative analysis through the ISARIC Partner Analysis scheme.5 External researchers were also welcome to submit proposals via the ISARIC Data Access process. These mechanisms support ISARIC’s mission to generate and share clinical research evidence rapidly. An illustrative example of ISARIC’s collaborative output is the number of publications over time, shown in Figure 1, highlighting the network’s sustained productivity and engagement. These publications cover diverse topics, including clinical outcomes, diagnostics, health systems, methods, genomics, immunology, treatments, and among other research areas.5

Figure 1. Peer-reviewed publications using ISAIRC COVID-19 Dataset

The challenges encountered during the COVID-19 response highlighted several critical lessons that have since shaped ISARIC’s approach to outbreak research and response (Figure 2).

Figure 2. COVID-19 ISARIC CCP Implementation and key takeaways.

They reinforced that, while curating a large and complex dataset is technically demanding, applying strategic principles can significantly improve efficiency, quality, and collaboration in future efforts. The key takeaways from this were that tools to facilitate outbreak research response should:

“Be flexible”: Outbreak contexts vary widely, and sites must have the autonomy to customise CRFs to their needs.

“Prioritise standardisation”: Consistent definitions and harmonised variables are critical for cross-site analysis.

“Respect decentralisation”: Local data ownership must be preserved, with centralised support focused on harmonisation rather than rigid control.

“Ensure global integration”: Data systems must be designed to integrate information from diverse sites maintaining coherence and quality.

“Capture the unanticipated”: Limited free-text fields are essential for recording unforeseen information and must be paired with scalable analysis methods.

“Be prepared for rapid insights”: Real-time analysis during outbreaks depends on having protocols, tools, and systems ready in advance.

“Rely on strong collaboration”: Secure, equitable, and inclusive data sharing, with recognition for all contributors, is essential to sustaining global engagement and high-quality evidence.

These lessons from creating the ISARIC COVID-19 dataset continue to inform ISARIC strategies for improving global outbreak preparedness and response.

While flexibility and standardisation may seem contradictory, both are essential to an effective outbreak response. Flexibility allows sites to adapt data collection to their specific contexts, while standardisation ensures that these data remain uniformly defined. Similarly, decentralisation and global integration are not opposing but complementary: preserving local data ownership and autonomy builds trust and engagement, while global integration ensures that diverse datasets can be harmonised to generate robust, collective evidence. Balancing these elements is critical to building a resilient, scalable, and inclusive research response framework.

CONCLUSIONS

Outbreak research requires infrastructure, standardised approaches, careful preparation, and, strong relationships. ISARIC’s experience during the COVID-19 response reinforced the principle that tools, such as collaborative frameworks and technological platforms, must be designed to respect diverse research contexts and empower local contributors to effectively strengthen outbreak preparedness. ISARIC is transforming global outbreak preparedness and clinical research to enable faster, higher-quality studies and promote equitable, data-driven healthcare, aiming to shape future outbreak responses and strengthen global health research systems.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust [303666/Z/23/Z]; UK International Development [301542-403]; and the Gates Foundation [INV-063472].

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTIONS

EGG: Conceptualization; Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Software; Supervision; Validation; Visualisation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing

TE: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Software; Validation; Visualisation; Writing – review & editing

SDV: Data curation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Methodology; Software; Validation; Visualisation; Writing – review & editing

DD: Data curation; Investigation; Validation; Writing – review & editing

BWC: Data curation; Project administration; Validation; Writing – review & editing

LFR: Investigation; Validation; Writing – review & editing

EPl: Investigation; Methodology; Validation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing

LM: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Investigation; Project administration; Resources; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing

REFERENCES

ISARIC. ISARIC Homepage. Published 2023. Accessed May 10, 2025, https://isaric.org/

Dunning JW, Merson L, Rohde GGU, et al. Open source clinical science for emerging infections. Lancet Infect Dis. Jan 2014;14(1):8-9. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(13)70327-x

ISARIC Clinical Characterization Group. The value of open-source clinical science in pandemic response: lessons from ISARIC. Lancet Infect Dis. Dec 2021;21(12):1623-1624. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(21)00565-X

Garcia-Gallo E, Merson L, et al. ISARIC-COVID-19 dataset: A Prospective, Standardized, Global Dataset of Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19. Sci Data. Jul 30 2022;9(1):454. doi:10.1038/s41597-022-01534-9

ISARIC. ISARIC Partner Analysis. Published 2023. Accessed May 10, 2025. https://isaric.org/research/isaric-partner-analysis-frequently-asked-questions/

Merson L, Duque S, Garcia-Gallo E, Yeabah TO, Rylance J, Diaz J, Flahault A, ISARIC Clinical Characterisation Group. Optimising Clinical Epidemiology in Disease Outbreaks: Analysis of ISARIC-WHO COVID-19 Case Report Form Utilisation. Epidemiologia. 2024; 5(3):557-580. https://doi.org/10.3390/epidemiologia5030039

Submit a Manuscript:

Copyright © Author(s) 2025. JASPI- Journal of Antimicrobial Stewardship Practices and Infectious Diseases.