Short-Term Assessment of Knowledge and Practices on Needle-Stick Injury Management among Healthcare Workers: An Educational Intervention Study

JASPI September 2025 / Volume 3 /Issue 3

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Citation: Kharchandy HL, Das A, Garh R,et al.Short-Term Assessment of Knowledge and Practices on Needle-Stick Injury Management among Healthcare Workers: An Educational Intervention Study. JASPI. 2025;3(3):15-21

DOI: 10.62541/jaspi095

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Needle stick injury is a serious occupational hazard to health care workers (HCWs) owing to the high potential of transmitting blood-borne viruses like HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C. The aim of this study is to assess the knowledge and practice among HCWs towards needle stick injuries (NSIs) management and to assess the improvement of the available knowledge and practice after interactive training sessions on the same.

Methods: A questionnaire-based interventional study on HCWs was conducted in the Trauma Centre, Banaras Hindu University. Interactive training sessions on NSI management were provided. Knowledge and practices were assessed before and after the training.

Results: A total of 138 HCWs participated in the study. Upon comparing the knowledge and practice among HCWs towards NSIs management before and after the training session, overall improvement were observed in knowledge regarding the utility of antiseptics (p<0.0001), bio-medical waste category of needles (p=0.043), pressing of the site following injury (p=0.0002), timing to take post-exposure prophylaxis (p=0.0429) and in practice in choosing proper container for needle disposal (p= 0.04).

Conclusion: The present study highlights the importance of assessing knowledge and practice to improve ways of management of NSI and emphasized the need of interactive training which resulted in improvement mostly in knowledge aspects.

KEYWORDS: Post-mortem microbiology; Sepsis; Antimicrobial stewardship

INTRODUCTION

Needle stick injury (NSI) is a serious occupational hazard to health care workers (HCWs) owing to the high potential of transmitting blood-borne infections like HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C1. Overuse of injections, recapping of needles after use, unavailability of disposable safe needle devices and sharps disposal containers, overburdened staff in the wards, emergencies, or operating rooms, performance of injury prone surgical procedures, passing instruments casually by hands in the operating room, lack of awareness about the hazard etc. are the factors which contribute to the increased risk of NSI2. In addition, high prevalence of blood-borne pathogens in communities in developing countries, as well as scarcity of basic protective measures like personal protective equipment (PPE), add to the severity of the problem, leading to serious consequences to the health care workers in these countries2,3.

NSI is a completely preventable hazard, if HCWs have proper knowledge and adopt appropriate preventive measures4. Comprehensive training that addresses institutional, behavioural, and device-related factors that contribute to the occurrence of NSI in HCWs can not only reduce the accident but also reduces the risk of transmitting blood borne viruses with prescribed line of management.

Considering the increasing incidence of NSI in Trauma centre, assessment of knowledge and practice of HCWs regarding NSI was crucial for the prevention and management of such accidents. The present study was conducted:

i) To assess the knowledge and practice among HCW towards NSI prevention and their approach to NSI management and

ii) To assess the improvement of the available knowledge and practice after dedicated training sessions on NSI management.

METHODOLOGY

Study design, participants and setting: A questionnaire-based interventional study was conducted in a 330-bedded level 1 Trauma Centre, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, during November and December 2019. HCW, including doctors, nurses, ward attendants, housekeeping staff, and technicians in the Trauma Centre, were approached for their voluntary participation in the study. Consenting participants were included. HCWs with work experience of less than six months in the healthcare sector were excluded from the study.

Pre-intervention phase: A pretested structured questionnaire (both in Hindi and English) was provided to each participant by the investigators, and they were asked to fill out their questionnaire within 30 minutes without consulting others. The study on HCWs was conducted from 1st to 31st December 2019 in the Trauma Centre, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi.

For assessment of knowledge, questions regarding the need of antiseptic use, PPE, colour coding category of needles as per Biomedical waste (BMW) rules 2016, variability of transmission risk with different types of needles, and timing to take PEP regimen following HIV contaminated NSI along with appropriate answers and distractors were included (Supplementary table 1).

Questions about | Before training n=138 |

Number of participants giving correct response | |

Whether antiseptic should be applied following NSI. Correct response: No | 40 |

Category of needles as per Bio-Medical Waste rules, 2016. Correct response: White | 98 |

Whether injured site should be pressed to express blood or not in case of needle stick injury. Correct response: No | 69 |

Type of needle with maximum chance of transmitting blood borne viruses. Correct response: Hollow bore needle. | 59 |

Timing of post exposure prophylaxis regimen to be taken following HIV contaminated needle stick injury. Correct response: As early as possible preferably <2 hours | 86 |

Specific questions about recapping of needles, passing of needles to others, disposal of needles after use, mutilation of needles before disposal, immediate measures adopted following NSI, and reporting of NSI were also added in the questionnaire to assess the practice among HCW.

The participants were specifically instructed not to mention their names or any identifier in the questionnaire. Multiple visits by the investigators were made to different wards, ICU and other areas of Trauma Centre over a week period in different shifts to collect maximum individual non-repetitive responses from HCWs.

Intervention phase: Interactive training sessions on Understanding NSI, Prevention of NSI, Immediate Management after NSI were arranged on different days (Investigators interacted with the different categories of HCWs differently: E.g. with the unskilled HCWs like housekeeping staff, there was separate training sessions to clarify different queries).

Post-intervention phase: Same set of questionnaire were provided to study participants who attended the training session(s) after two weeks of attending the training to assess the improvement in knowledge and practice towards NSI management.

Data processing: The responses of the study participants were tabulated in the MS excel using a unique letter/ code for a particular response to a specific question. The available knowledge and practice were analysed as proportions of total participants and/or the sub-groups based on the occupations, viz., nursing officers, technicians, housekeeping staff, etc.

Statistical analysis: For comparison, cumulative correct responses for different questions before and after the training session were analysed with Fisher’s exact test using SPSS for Windows Version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Ethical statement: The permission for conducting this study was granted by the Institutional Ethics Committee (vide letter No. DEAN/2019/EC/1674 dated November 18, 2019).

RESULTS

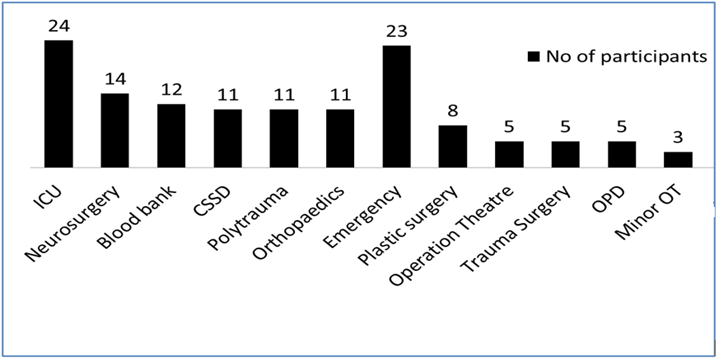

Baseline assessment: A total of 138 HCWs (Doctors= 9, Nurses= 70, Ward attendants= 19, House-keeping staff= 18, Multipurpose HCW= 13, Technicians= 9) voluntarily participated in the study. Figure 1 depicts the distribution of the participants posted in different areas of the hospital. Among all the participants, only 68.8% had prior training on hospital infection control addressing NSI management before the educational intervention conducted during the present study. Of 138 participants, 127 (92%) participants were found to be vaccinated against Hepatitis B, but only 99 (78%) completed the full course whereas only one and two doses were received by 10 (8%) and 18 (14%) participants, respectively.

Figure 1: Distribution of the participant healthcare workers, posted in different areas of the Trauma Centre (N=132).

At baseline, among HCWs, 50 (36.23%) sustained injuries with a needle in the present hospital, mostly with hollow-bore syringe needles (44; 88%). Most of the events of NSI occurred while giving injections to the patients (22; 44%), followed by segregating BMW (12; 24%), drawing a blood sample (8; 16%), respectively. Injuries inflicted by needle sticks mostly involved fingers (44; 88%), followed by palms (5; 10%) and legs (1; 2%). Among the total 50 cases of NSI, the serological status of source patients was known in 27 (54%) cases (HIV antibody reactive =1, HBsAg reactive =5, Anti-HCV antibody reactive =3, sero-negative =18). Further, 33 participants (23.9%) had suffered from sharp injuries (broken ampule=24, surgical blade=6, others=3) other than needle stick injuries.

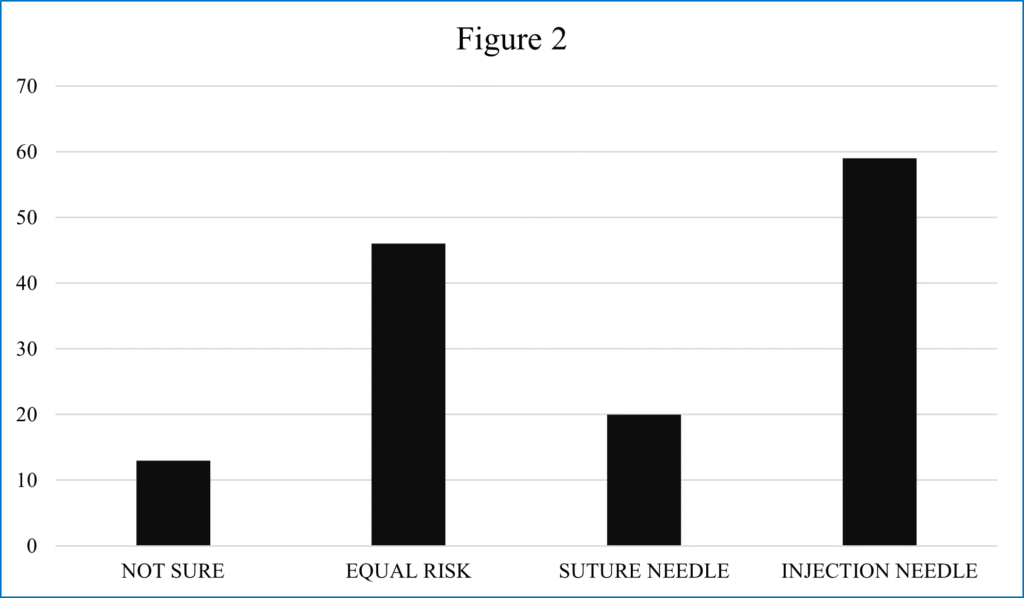

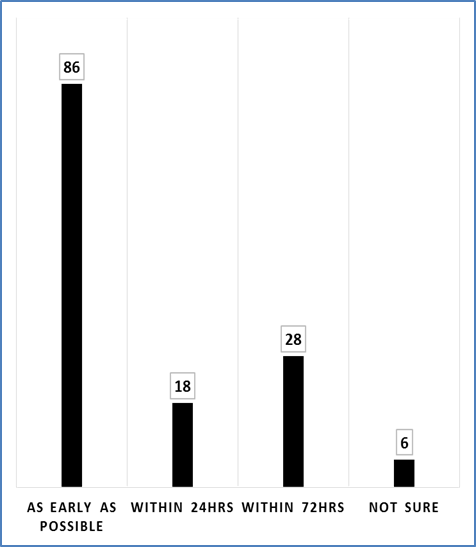

Assessment of knowledge: Among all the participants, 74 (53.6%) answered that antiseptics should be applied following NSI, whereas 40 (28.9%) opposed the view, and 24 (17.5%) were not sure about the answer. Sixty-nine (50%) participants answered that the injured site should not be pressed to express blood following NSI, while the remaining participants were either in favour of expressing blood (49; 35.5%) or not sure about the answer (20; 14.5%). Regarding category of needles as per BMW rules, 20165, 98 (71.01%) mentioned correctly the colour coding of needles (white or transparent). The available knowledge about risk of blood-borne viruse transmission with different types of needles and timing to take PEP regimen following HIV contaminated NSI were depicted in Figure 2, 3 respectively.

Figure 2: Bar diagram depicting knowledge about type of needle with maximum transmission risk of blood borne viruses (N=138)

Figure3: Bar diagram knowledge about timing to take post-exposure prophylaxis regimen following HIV contaminated Needle stick injury (N=138)

Assessment of practice: In practice, 76 (55.07 %) HCWs always recapped the needles after use and 20 (14.5%) HCWs sometimes recapped. Immediately after use, 102 (73.9%) respondents put the needle in designated white puncture proof container while others kept on medicines trolley (24; 17.4%) or near the bedside (3; 2.2%) or passed to others for disposal (9; 6.5%). To pass sharp instruments to others, kidney tray, forceps, double gloved hands and bare hands were preferred by 73 (52.9%), 41 (29.7%), 19 (13.8%) and 5 (3.6%), respondents respectively. Only 9 (6.5%) among all HCW never mutilated needles before segregation.

Among the participants with history of injury with needle, 46 (92%) HCWs washed the injured area under running water for 15mins, only one HCW (2%) put finger reflexly inside mouth and 4 (8%) HCWs did not follow the immediate care.

Assessment of knowledge after training: Total of 77 participants took part in the interactive training sessions on NSI management. After two weeks post training, 54 participants filled up the questionnaire to document their knowledge and practice after training. The comparison of correct/appropriate responses about knowledge and practice before and after training were depicted in table 1 and 2.

Table I: Assessment of Knowledge of HCWs before and after training on needle stick injury.

Questions about | Before training n=138 | After training n=54 | p value |

Number of participants giving correct response | Number of participants giving correct response | ||

Should antiseptic be applied following NSI? Correct response: No | 40 (28.98%) | 37 (68.51%) | <0.00001 |

Category of needles as per Bio-Medical Waste rules, 2016. Correct response: White | 98 (71%) | 46 (85.18%) | 0.043 |

Should the injured site be pressed to express blood in case of needle stick injury? Correct response: No | 69 (50%) | 43 (79.62%) | 0.0002 |

Type of needle with maximum transmission risk of blood borne viruses. Correct response: Hollow bore needle. | 59 (42.75%) | 31 (57.4%) | 0.0778 |

Timing of post exposure prophylaxis regimen to be taken following HIV contaminated needle stick injury. Correct response: As early as possible preferably <2 hours | 86 (62.31%) | 42 (77.77%) | 0.0429 |

Table 2: Assessment of practices regarding needle disposal before and after training on needle stick injury

Questions | Before training n=138 | After training n=54 | p value |

Number of participants giving appropriate response | Number of participants giving appropriate response | ||

Do you recap the needles after use? Appropriate response: Never | 42 (30.4) | 21 (38.9) | 0.3058 |

Where do you put the needle immediately after use? Appropriate response: White sharp container | 102 (73.9) | 47 (87.03) | 0.049 |

How do you transfer any sharp objects to others? Appropriate response: In a kidney tray | 73 (52.8) | 29 (53.7) | 1 |

Do you mutilate the needles before disposal? Appropriate response: Never | 31 (22.4)

| 3 (24.0) | 0.85 |

DISCUSSION

NSI is defined as injury caused by accidental penetration of skin by a needle6. A report published in 2015 mentioned that globally 35 million HCWs were at risk of having such accident at their workplaces7. This huge population of HCWs worldwide always bear the threat of acquisition of HIV infection and other viral infections (HCV and HBV) due to accidental exposure to needles contaminated with infected blood and body fluids8. Following NSI, the transmission risk ranges from 1.9% to >40% in HBV infections, 2.7% to 10% in HCV infections, and 0.2% to 0.44% in HIV infections9. Besides causing serious morbidity and fatality, these infections also have associated social and psychological issues, further aggravating the problems of the victim.

The incidence and prevalence data on NSI in Indian hospitals are scarce in the literature. Moreover, the incidents are markedly under-reported throughout the world10. Assumptions about the absence of blood-borne pathogens in the source patients, lack of knowledge to report and annoyance are the main factors that lead to under-reporting11. In the present study, only 27 of the total 50 cases (54%) of injury with a needle were reported to the infection control team.

Increased workloads, prolonged work shifts, needle recapping, lack of proper training and knowledge can be significantly associated with NSI12. A study by Kimaro et al reported that recapping contributed more to the occurrence NSI13. In the present study, needle recapping was practised by 69.5% participants, and among those participants with a hollow bore NSI (n=44), 86.36% practiced recapping. In a similar recent study conducted in Nepal by Singh et al, needle recapping was also found as a common practice14.The same study also depicted a high prevalence of NSI (70.3%) among health workers with 47.9% responders to the questionnaire to assess knowledge experiencing >1 time injury in their career14, whereas in our study, 36.23% of responders had a history of injury with needle. Singh et al. reported that maximum injuries with needle occurred while passing the sharp in a tertiary care eye hospital15. Same study also mentioned that maximum number of NSI occurred in operating theatre (67%) followed by laboratory (12%) and patient wards (10%)15. We observed that maximum number of NSI occurred in different wards (59.09%) of the hospital and improper transfer of sharps (i.e. by direct hands, forceps) was a common practice among our participants (47%).

A study conducted in four tertiary hospitals in Lao People’s Democratic Republic documented that attendance to educational or refresher courses on safety regarding NSI was one of the key protective factors against this occupational menace16. Although we have observed that significant improvement has occurred in knowledge after training regarding need of antiseptic use (p<0.00001), pressing of injured site to express blood (p=0.0002), colour coding category of needles as per Biomedical waste (BMW) rules (p=0.043) and timing to take PEP regimen following HIV contaminated NSI (p=0.0429), there were no significant improvement in terms of different practices except disposal of needles in appropriate white container (p= 0.049). Although the major improvement could not be assessed in terms of practice because of the shorter time span of the study, a perceptible improvement in knowledge was observed after the training sessions. This may be due to the fact that safe needle practices, as a behavioural modification, usually take time to show improvement. The major limitations of the present study are that it was questionnaire-based assessment of knowledge only after two weeks training sessions and no skill-based assessment was made during the study period. Neither sustained improvement in knowledge and preventive practice nor improvement in management of NSI could be judged from the findings.

CONCLUSION

The present study was the first of its kind conducted in a tertiary care centre of the region to highlight the importance of assessing knowledge and practice to improve ways of management of NSI. While recapping of needles, improper way of transfer of needles, lack of knowledge about use of antiseptics, and timing to take PEP regimen were major lacunae among HCWs, interactive training could result in improvement, mostly in knowledge and a few practices on NSI management. Continued training and assessment are required for long-term improvement and sustainability of knowledge and practice about NSI.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

NA

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

None

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

HLK: Conceptualization; Training of HCWs; Literature review; Data curation; Drafting of manuscript

AD: Develop questionnaire; Methodology; Training of HCWs; Analysis; Review & editing.

RG: Develop questionnaire; Methodology; Training of HCWs; Analysis, Review & editing.

RS: Develop questionnaire; Methodology; Analysis.

PP: Training of HCWs; Supervision, Validation, Review & editing

DECLARATION FOR THE USE OF GENERATIVE ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI) IN SCIENTIFIC WRITING: There is no use of generative Artificial Intelligence (AI) in scientific writing

REFERENCES

Malhotra S, Sharma S, Bhatia NJ, Hans C. Needle-stick injury among health care workers and its response in a tertiary care hospital. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2016 Apr 1;34(2).

Wilburn SQ, Eijkemans G. Preventing needlestick injuries among healthcare workers: a WHO-ICN collaboration. International journal of occupational and environmental health. 2004 Oct 1;10(4):451-6.

Goodnough CP. Risks to health care workers in developing countries. The New England journal of medicine. 2001 Dec 1;345(26):1916.

Ananthachari KR, Divya CV. A cross sectional study to evaluate needle stick injuries among health care workers in Malabar medical college, Calicut, Kerala, India. International Journal Of Community Medicine and Public Health. 2016;3(12):3340-4.

Government of India, Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change. Bio-Medical Waste (Management and Handling) Rules, 1998. Published in: The Gazette of India: Extraordinary, Part II, Section 3, Sub-section (ii). New Delhi: Government of India; 2016 Mar 28 [cited 2025 September 5]. Available from: https://moef.gov.in/

Akeem BO, Abimbola A, Idowu AC. Needle stick injury pattern among health workers in primary health care facilities in Ilorin, Nigeria. Academic Research International. 2011 Nov 1;1(3):419.

Gopar-Nieto R, Juárez-Pérez CA, Cabello-López A, Haro-García LC, Aguilar-Madrid G. Overview of sharps injuries among health-care workers. Revista Médica del Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. 2015 May 18;53(3):356-61.

Doig C. Education of medical students and house staff to prevent hazardous occupational exposure. CMAJ. 2000 Feb 8;162(3):344-5.

Dilie A, Amare D, Gualu T. Occupational exposure to needle stick and sharp injuries and associated factors among health care workers in Awi Zone, Amhara Regional State, Northwest Ethiopia, 2016. Journal of environmental and public health. 2017;2017(1):2438713.

Kim OS, Jeong JS, Kim KM, Choi JS, Jeong IS, Park ES, Yoon SW, Jung SY, Jin HY, Chung YK, Lim KC. Underreporting rate and related factors after needlestick injuries among healthcare workers in small-or medium-sized hospitals. Korean Journal of Nosocomial Infection Control. 2011:29-36.

Memish ZA, Assiri AM, Eldalatony MM, Hathout HM, Alzoman H, Undaya M. Risk analysis of needle stick and sharp object injuries among health care workers in a tertiary care hospital (Saudi Arabia). Journal of epidemiology and global health. 2013 Jan;3(3):123-9.

Kaweti G, Abegaz T. Prevalence of percutaneous injuries and associated factors among health care workers in Hawassa referral and adare District hospitals, Hawassa, Ethiopia, January 2014. BMC public health. 2015 Dec;16(1):8.

Kimaro L, Adinan J, Damian DJ, Njau B. Prevalence of occupational injuries and knowledge of availability and utilization of post exposure prophylaxis among health care workers in Singida District Council, Singida Region, Tanzania. PLoS One. 2018 Oct 25;13(10):e0201695.

Singh B, Paudel B, Kc S. Knowledge and practice of health care workers regarding needle stick injuries in a tertiary care center of Nepal. Kathmandu University Medical Journal. 2015;13(3):230-3.

Rishi E, Shantha B, Dhami A, Rishi P, Rajapriya HC. Needle stick injuries in a tertiary eye-care hospital: Incidence, management, outcomes, and recommendations. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2017 Oct 1;65(10):999-1003.

Matsubara C, Sakisaka K, Sychareun V, Phensavanh A, Ali M. Prevalence and risk factors of needle stick and sharp injury among tertiary hospital workers, Vientiane, Lao PDR. Journal of occupational health. 2017 Nov;59(6):581-5.

Submit a Manuscript:

Copyright © Author(s) 2025. JASPI- Journal of Antimicrobial Stewardship Practices and Infectious Diseases.