Outpatient Antimicrobial Parenteral Therapy (OPAT) in Indian Setting - An Update

JASPI December 2024/ Volume 2/Issue 4

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Panda PK, Mathur A. Outpatient Antimicrobial Parenteral Therapy (OPAT) in Indian Setting – An Update. JASPI.2024;2(4):1-4 DOI: 10.62541/jaspi058

INTRODUCTION

Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT), often delivered via hospital in-home services, is the management of infections outside the hospital setting in the community or at home by administration of more than one dose of parenteral antimicrobials on different days.1 The first documented OPAT practice was in 1974 for the treatment of chronic bronchopulmonary infection in a paediatric population.2 A year later, it expanded into the adult population, including self-administration of parenteral antimicrobials.3 In recent years, OPAT has seen considerable growth in middle-to high-income countries due to its significant benefit to the healthcare system and patients.4,5 OPAT is considered part of regular care in many countries across Europe, Asia, North America, and Oceania. It is a safe, effective, and cost-saving practice.6 Although each small clinic regularly practises it in India, structured OPAT is rarely practised. Hence, it is difficult to say whether it is efficacious in our set-up, including its safety.

OPAT is routinely employed for patients requiring intravenous antimicrobial therapy for a variety of infective conditions, including endocarditis, osteomyelitis, and prosthetic joint infection, enabling early hospital discharge. For some conditions (such as cellulitis), initiating OPAT in the outpatient or emergency department setting may allow hospitalisation to be avoided entirely.7

As part of broader antimicrobial stewardship efforts, OPAT enables the rational use of antimicrobials, thus significantly combating antimicrobial resistance (AMR), especially by reducing hospital-acquired infections (HAIs), a growing global health concern.8 However, despite its benefits, the widespread adoption of OPAT faces several barriers, while various facilitators exist that can enhance its practice. Risks of ОРΑΤ include catheter-related complications, unwitnessed adverse drug events, reduced frequency of clinical oversight in comparison to hospitalisation, and dangers posed by the provision of care by patients and caregivers who may have no formal medical training. While OPAT carries inherent risks, these can be mitigated through a systematic approach that adheres to established guidelines and best practices. There is a need for robust microbiology infrastructure and support for pathogen identification and antimicrobial susceptibility determination, which is generally lacking in most places in India.

CLINICAL UTILITY OF OPAT

A recent pilot longitudinal study conducted at AIIMS Rishikesh by Mathur A. et al. has demonstrated that OPAT is a 100% safe and effective alternative to traditional hospitalisation.9

The pilot study, involving 20 patients treated with OPAT, has reaffirmed the potential of this modality to effectively manage a range of infections, from complicated urinary tract infections to acute pyogenic meningitis. The results are promising: 19 out of 20 patients achieved clinical improvement, with many demonstrating resolution of symptoms within two weeks. This aligns with global findings that support OPAT’s efficacy, as seen in other studies where high success rates and low readmission rates were reported. Despite a single case of thrombophlebitis and one readmission due to logistical issues, the overall safety profile of OPAT was favourable. The comprehensive, structured monitoring system used in this study allowed for the early detection and management of complications, underscoring OPAT’s potential as a safe alternative to inpatient care. Telemedicine and support systems are essential for managing OPAT in remote patients, enabling efficient monitoring and timely intervention while reducing the need for frequent in-person visits.

One of the most significant findings from this study is the reduction in hospitalisation duration. Transitioning patients to OPAT cut the average hospital stay by two weeks. This reduction not only translates to cost savings but also optim ises the use of hospital resources, freeing up beds for more critical cases and mitigating the risk of nosocomial infections. In resource-limited settings, such as India, where hospital beds are often in high demand, the ability to provide effective treatment outside of the hospital setting can make a substantial difference. The study’s findings highlight how OPAT can alleviate pressures on healthcare systems by enabling patients to continue treatment in the comfort of their homes.

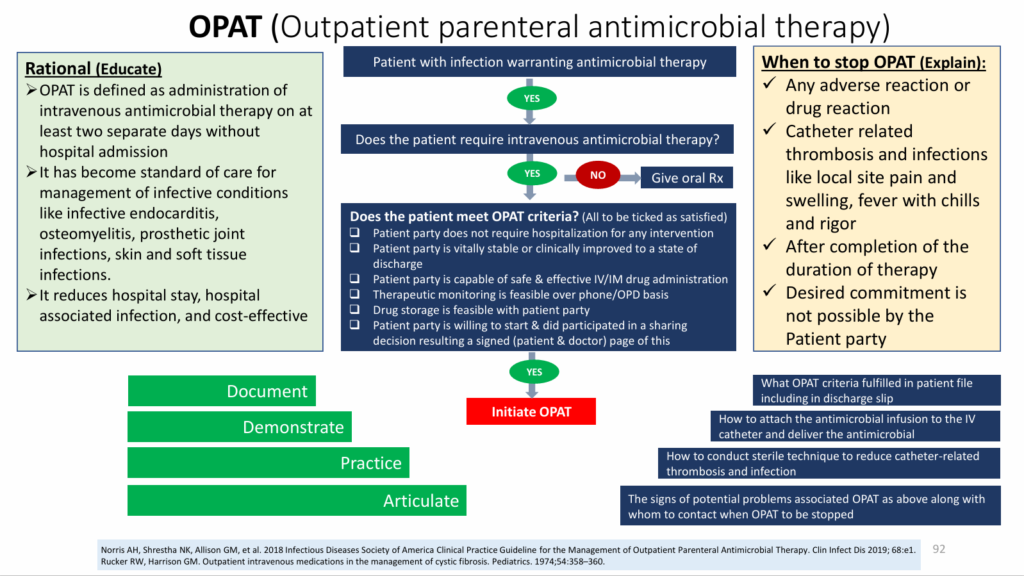

Figure 1: OPAT blueprint, designed to ensure smooth implementation while minimising complications.

OPAT’s alignment with patient-centred care principles is another key advantage. Patients receiving OPAT could continue their treatment in familiar surroundings, providing a more positive healthcare experience. This approach improves patient satisfaction and enhances adherence to treatment regimens.

While the study highlights OPAT’s potential, it also identifies several challenges. Approximately half of the patients did not receive pre-discharge education, which could impact the effectiveness of the therapy. Additionally, the study’s small sample size and single-centre design limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research involving larger, multi-centre studies must validate these results and explore OPAT’s broader applicability.

Addressing the logistical challenges, such as ensuring the availability of medication and trained caregivers, is crucial for implementing OPAT successfully. Adequate funding and dedicated healthcare teams are necessary to overcome these barriers and optimise OPAT delivery. Especially in India, where cost was out of pocket the majority of times before the Ayushman Bharat Scheme era, it would have been cheaper to go for OPAT rather than hospitalisation. However, this scheme doesn’t help in the rate of HAIs; instead, it will increase the rate by shadowing the absolute need for hospitalisation. The government should focus on extending these injectables in the home under OPAT through this scheme to have balanced approaches.

OPAT SKILL

All admitted patients requiring prolonged parenteral antimicrobial therapy should be evaluated for OPAT eligibility using a standardised checklist [Figure 1].

After the need for IV antimicrobial therapy has been verified, candidates for home-based ОPAΤ must be evaluated to ensure they are medically stable, able, and willing to self-administer intravenous antimicrobial treatment (or have a caregiver who can do so). Administering antibiotics by trained healthcare providers is often not feasible in all cases. Still, home healthcare services can administer antibiotics with daily telephonic monitoring by treating physicians. In general, ОРAΤ is not possible for homeless patients; in such cases, ОРΑΤ in a medical respite setting may be feasible.10 Insert the vascular device and demonstrate comprehensively to the patient/caregiver how to administer antibiotic infusions under aseptic conditions. This includes guidance on proper vascular device care, such as daily dressing, keeping the device covered with a sterile cap, and cleaning the surrounding area with Betadine-soaked cotton three times daily. Ensure they understand the importance of replacing the vascular device every third day or immediately if fever, pain, redness, or pus discharge develops at the cannula site. Counsel and motivate the patient to adhere strictly to OPAT, maintain daily communication with the treating physician, and report immediately to the nearest hospital in case of any serious adverse effects. The consequences of using high-end antimicrobials in community settings also carry the risk of AMR, as disposal of used antibiotic vials cannot be supervised. To mitigate it, strict protocols for the safe disposal of used antibiotic vials should be implemented, alongside patient education on proper usage and disposal practices.

Upon discharging the patient with OPAT instructions, daily telephonic follow-ups by the treating physician are essential. These calls should monitor the patient’s progress, identify any complications related to the drug or vascular device, determine the appropriate time for transitioning from parenteral to oral therapy, and decide when to discontinue OPAT and schedule follow-ups.

CONCLUSION

OPAT has proven to be a highly effective and valuable alternative to traditional inpatient care in India, as per this pilot study, offering substantial benefits regarding patient safety, cost-efficiency, and antimicrobial stewardship. Despite its potential, the widespread adoption of OPAT in India faces several challenges, including insufficient healthcare worker training, communication gaps, and inadequate infrastructure. Overcoming these barriers through comprehensive training, standardised protocols, and robust monitoring systems is crucial for implementing OPAT successfully. At least, each medical college that caters to the most serious admitted patients and those in recovery can quickly implement this OPAT Blueprint. Furthermore, ensuring patient adherence through consistent follow-ups and providing adequate support for self-administration are essential to optimising its impact. With careful planning and execution, OPAT has the potential to transform Indian infection management or in any resource-constrained settings to reduce the strain on healthcare facilities and play a significant role in combating AMR, ultimately improving the quality of care for patients.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

None

REFERENCES

-

Norris AH, Shrestha NK, Allison GM, et al. 2018 Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(1):e1-e35.

-

Rucker RW, Harrison GM. Outpatient intravenous medications in the management of cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 1974;54(3):358-60.

-

Antoniskis A, Anderson BC, Van Volkinburg EJ, Jackson JM, Gilbert DN. Feasibility of outpatient self-administration of parenteral antibiotics. West J Med. 1978;128(3):203-6.

-

Emilie C, de Nocker P, Saïdani N, et al. Survey of delivery of parenteral antimicrobials in non-inpatient settings across Europe. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2022;59(4):106559.

-

Chapman AL, Seaton RA, Cooper MA, et al. Good practice recommendations for outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) in adults in the UK: a consensus statement. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67(5):1053-62.

-

Wijnakker R, Visser LE, Schippers EF, Visser LG, van Burgel ND, van Nieuwkoop C. The impact of an infectious disease expert team on outpatient parenteral antimicrobial treatment in the Netherlands. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41(1):49-55.

-

Yadav K, Suh KN, Eagles D, Thiruganasambandamoorthy V, Wells GA, Stiell IG. Evaluation of an emergency department to outpatient parenteral antibiotic therapy program for cellulitis. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(11):2008-14.

-

Barr DA, Seaton RA. Outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) and the general physician. Clin Med (Lond). 2013;13(5):495-9.

-

Mathur A, Panda PK, Kant R, et al. A Pilot Longitudinal Study to Evaluate the Efficacy, Safety, and Feasibility of Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy and to Identify Real-World Barriers and Facilitators in a Resource-Limited Setting. medRxiv 2024.08.19.24312236. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.08.19.24312236

-

Beieler AM, Dellit TH, Chan JD, et al. Successful implementation of outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy at a medical respite facility for homeless patients. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(8):531-5.

Submit a Manuscript:

Copyright © Author(s) 2024. JASPI- Journal of Antimicrobial Stewardship Practices and Infectious Diseases.