Integrated Antimicrobial Stewardship in India: Consensus on Best Practices, Current Baseline, and Identified Barriers

JASPI December 2024/ Volume 2/Issue 4

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Singh H, Panda PK, Patro S, et al.Integrated Antimicrobial Stewardship in India: Consensus on Best Practices, Current Baseline, and Identified Barriers. JASPI. 2024;2(4):32-45 DOI: 10.62541/jaspi054

ABSTRACT

Background: India faces unique challenges in tackling antimicrobial resistance (AMR) due to the high prevalence of infections, irrational antibiotic use, and varied healthcare infrastructure. Integrated stewardship practices are key to combating AMR. This study uses a questionnaire to assess the prevalence and barriers to integrated antimicrobial stewardship across tertiary healthcare settings, proposing actionable strategies for improvement.

Methods: This cross-sectional Delphi survey under the Society of Antimicrobial Stewardship PractIces (SASPI) Consortium assessed integrated antimicrobial stewardship (IAS) practices across 31 Indian tertiary care institutions. Using a validated 42-item questionnaire, it evaluated stewardship programs, accountability, prescriber education, laboratory protocols, and infection control. Data were analysed using SPSS. Practices were analysed as subcategories- administrative, antimicrobial, diagnostic, and infection prevention stewardships.

Results: 44 responses from 31 tertiary care institutions in India, including 67.7% of institutes of national importance (INI), were analysed. 61.4% of the respondents were members of their hospital’s infection control committee (HICC) or antimicrobial stewardship program (AMSP). The validation of 42 practice statements showed that 41 received over 75% agreement, with adjustments to Practice Statement 6 (72.4%). Key findings revealed poor compliance in a few areas: 29% for assigning pharmacists the antimicrobial utilisation responsibility, 13% for OPAT policies, and 29% for having policies dealing with local infectious diseases. INIs reported lower compliance with integrated stewardship practices than non-INIs, possibly due to the involvement of experts who were not HICC/AMSP members in non-INIs. Key barriers were limited resources, inadequate diagnostic facilities, and a workforce in 42% of the institutes.

Conclusion: The study highlights the need for awareness and implementation of IAS practices in tertiary healthcare institutes in India. Addressing this requires the implementation of these practice statements, regular monitoring, resource allocation, training, and collaboration. SASPI can lead to collaboration. Policymakers and institutions must work together to integrate IAS fully, reducing AMR and improving patient outcomes across India.

KEYWORDS: Antimicrobial resistance; Stewardship, Delphi survey; Diagnostic stewardship; Infection prevention stewardship; SASPI

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a critical global health challenge, threatening the efficacy of life-saving treatments and increasing morbidity and mortality due to infections.1 India, one of the world’s most populous nations, faces unique challenges in tackling AMR, exacerbated by the high prevalence of infectious diseases, varied healthcare infrastructure, and widespread antimicrobial use in human, plant, and animal healthcare sectors. The irrational use of antimicrobials, over-the-counter availability, lack of regulation, and improper prescription practices contribute significantly to the alarming rise of AMR in India. In response, antimicrobial stewardship programs (ASPs) have been increasingly recognised as a key public health strategy to promote the responsible use of antimicrobials.

Antimicrobial stewardship aims to optimise antimicrobial selection, dosage, and duration of therapy to balance effective infection control with minimising the risk of resistance development. However, effective antimicrobial stewardship relies on proper infection prevention stewardship (ISP) and diagnostic stewardship (DSP) practices, as ASP alone will not solve the global AMR issue. Thus, an integrated stewardship practice (ISP, DSP, ASP) is necessary for a comprehensive approach to healthcare structures.2 Globally, ASPs have shown promise in reducing antimicrobial misuse, decreasing the incidence of resistant infections, and improving patient outcomes. However, in India, the implementation of such programs, including ISP and DSP, has been uneven across regions and healthcare facilities, mainly due to high antibiotic use, lack of awareness, inadequate infrastructure, inadequate funding, disparity between public and private sectors, limited surveillance capabilities and cultural beliefs.3-5

Assessing the prevalence of ASP or integrated stewardship practices provides a critical understanding of how frequently and effectively these practices are employed in various healthcare settings.3 Given the diversity of India’s healthcare system—comprising public and private providers, urban and rural facilities, and variable levels of access—comprehensive analyses of stewardship practices can offer valuable insights into the efficacy of current interventions and help identify gaps that require attention.

This study seeks to provide a detailed overview of the prevalence of integrated antimicrobial stewardship (IAS) practices in India by utilising a Delphi questionnaire-based survey under the Society of Antimicrobial Stewardship PractIces (SASPI) Consortium across tertiary-level healthcare settings in institutes of national importance (INIs) and few non-INIs. SASPI is an organisation dedicated to achieving the goal of “One Health”, which emphasises the interconnected well-being of humans, animals and the environment through integrated antimicrobial stewardship. The Delphi method, known for gathering expert consensus in complex, uncertain scenarios, is well-suited for exploring IAS practices in India’s varied healthcare settings, where expert insight is critical for establishing evidence-based guidelines.6

The study aims to find the agreement on IAS practice statements, baseline compliance to the existing IAS practices, and finally extract reasons why practices are not followed so that practice statement guidelines can be made for real-world settings. This analysis will contribute to a deeper understanding of strengthening these practices nationwide and propose actionable strategies for healthcare policymakers, hospital administrators, and clinicians.

METHODOLOGY

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study utilised a Delphi survey to assess the prevalence and status of institutional IAS practices across selected tertiary care institutes in India (Figure 1). The Delphi method involved one round of expert validations and two rounds of consensus-building using structured questionnaires. The study surveyed experts from tertiary care institutes selected based on their prominence in healthcare, including INIs and non-INIs who are SASPI members’ affiliated institutes. A panel of experts from various disciplines was invited to participate in the Delphi survey. The study was conducted under the supervision of the SASPI in India.

Participants and inclusion or exclusion criteria

Institutions eligible to participate had to have an active integrated stewardship program (ISP, DSP, or ASP) in full or partial form. Each institution was required to have at least one representative from the following: a physician, a surgeon, a microbiologist, a pharmacologist, a practising infection control nurse (where available), and a community physician (where available). Institutions that declined consent or were outside the tertiary care category, such as secondary hospitals or individual clinics, were excluded.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Institutional Ethics Committee of AIIMS, Rishikesh (Approval No. AIIMS/IEC23/322, dated 26/09/2023). Data collection began following the approval, and all research procedures adhered to ethical standards for human participant involvement. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent before completing the survey. Confidentiality was maintained throughout the data collection process, and no personal or institutional identifiers were included in the final analysis.

Data collection process

This involved three phases of the Delphi survey.

Phase 1 included preparing a structured questionnaire of 42 practice statements by three experts (Infectious disease specialists, pharmacologists, and microbiologists) using the Delphi method through multiple online meetings to evaluate various aspects of IAS implementation in the Indian tertiary care health system. The questionnaire was divided into four sections:

General administrative framework – 5 statements

Bedside practices of antimicrobial use – 11 statements

Practices of the clinical microbiology laboratory – 14 statements

Infection control practices – 12 statements

Figure 1: India map showing the participation of 31 institutes with pan-India representations.

The questionnaire assessed active stewardship programs, accountability mechanisms, prescriber education, antimicrobial use policies, laboratory protocols, clinical microbiology support, and infection control measures. Additionally, it examined whether institutions followed international guidelines for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (e.g., Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST)), maintained a digital AMR database (e.g., WHONET), and conducted regular audits for hand hygiene, biomedical waste segregation, and infection surveillance.

After preparation in phase 1, the questionnaire was administered online to validate them, and responses were collected from 31 institutions’ SASPI members, including 21 INIs as another set of experts. Each institution’s designated participant was an expert responsible for observing/practising daily IAS practices, providing a holistic view of stewardship practices at the institutional level. These respondents were from active SASPI member lists; all data were collected confidentially. The relevance and clarity of each practice statement were assessed and scored from 0 to 3. A score of ≥2 was considered relevant or clear. This constituted Phase 2 of the study. Following validation, each expert stated whether the specific practices were being followed in their institute to determine the random prevalences of these practices. The barriers to the practice statements were also collected as open-ended questions.

Phase 3 of the survey included sending the questionnaire back to phase 1 experts to modify and finalise, according to the experts’ feedback in the second validation, for revalidation. Once finalised, this questionnaire was re-confirmed to reach a consensus with all experts of these 3 phases in another online meeting.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered into a standardised database and analysed using SPSS (version 26). Descriptive statistics, including measures of central tendency (mean, median) and dispersion (standard deviation, range), were calculated to summarise the prevalence of IAS practices.

For each question, consensus was defined as a 75% agreement among participants, a threshold commonly used in Delphi studies to ensure a robust level of expert agreement on complex topics.

RESULTS

A total of 44 responses were received from 31 tertiary care institutions in India. 67.7% (21) of the institutes were Institutes of National Importance (INIs), and the rest were non-INIs (10). The institutes that participated in the study are listed in Table 1. The duration of work experience in the experts’ current institutes ranged from 1 year to 25 years, with the mean work duration being 5.73 years. Out of 44 responses, 27 experts (61.4%) were members of their hospital’s infection control committee (HICC) or antimicrobial stewardship program (AMSP) members. 58.1% of the institutes that responded had at least one expert as a member of the HICC/AMSP.

INIs |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bathinda |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bibinagar |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bilaspur |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhopal |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Deoghar |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Gorakhpur |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Guwahati |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Kalyani |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Madurai |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Mangalagiri |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Nagpur |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Patna |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raebareli |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur |

All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh |

Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, Puducherry |

North Eastern Indira Gandhi Regional Institute of Health and Medical Sciences |

Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh |

Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow |

Non-INIs |

Believers Church and Medical College Hospital, Kerala |

Bharati Vidyapeeth (DTU) Medical College, Pune |

Institute of Medical Sciences & SUM Hospital, Bhubaneshwar |

JSS Hospital, Mysore |

Medical College, Baroda |

Nizams Institute of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad |

Pondicherry Institute of Medical Sciences, Puducherry |

Rajarajeswari Medical College and Hospital, Bengaluru |

Sree Gokulam Medical College and Research Foundation, Kerala |

Sri Guru Ram Das Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Amritsar |

Note: INI – Institute of National Importance.

Forty-four experts from 31 institutions validated the practice statements. As seen in Table 2, most respondents agree with the practice statements provided in the questionnaire. As 41 items received validation by more than 70% of respondents, these practice statements were considered validated. Practice statements were modified as per comments received to make them 100% relevant and clear.

Table 2: Expert validation of IAS practice statements through the Delphi process (Pan-India representations) | |||

1 | The institution should have an actively running IAS program, either in whole or in fragments of ISP, DSP, and ASP but with the intention of integration. | 83.3% | 85.7% |

2 | The institution should have set accountability levels for various activities of the stewardship committee. | 90.0% | 82.1% |

3 | The clinical department should have defined accountability for rational antimicrobial use. | 85.7% | 86.7% |

4 | The institute should provide education regularly to prescribers and other relevant staff including patients/public on IAS Practices and institute outcomes for the same | 88.0% | 80.8% |

5 | The institute should set various levels of accountability and responsibility on the pharmacologist or pharmacist for ensuring rational antimicrobial use | 77.8% | 80.8% |

6 | The institute stewardship committee should review prescriptions of the whole hospital regularly | 86.2% | 72.4% |

7 | The institute should perform prospective audits and retrospective feedback for specific antimicrobial agents regularly | 89.3% | 81.5% |

8 | The institute should preauthorize the use of specific antimicrobial agents for specific infections | 82.8% | 80.0% |

9 | The institute should have practicing documents on PK/PD of specific antimicrobial agents | 89.3% | 82.1% |

10 | The institute should have dynamic facility-specific ID treatment recommendations, based on national guidelines and local antibiogram | 92.3% | 83.3% |

11 | The institute should have a policy that requires prescribers to document in the medical record or during order entry a dose, delivery, duration and indication for all antimicrobial prescriptions | 92.3% | 96.0% |

12 | The institute should have a policy that specifies IV to oral switch practices | 92.9% | 88.0% |

13 | The institute should have a policy that specifies Antimicrobials timeout practices | 85.7% | 85.2% |

14 | The institute should have a policy that specifies Antimicrobials ADR/SAE reporting’ practices | 95.8% | 95.7% |

15 | The institute should have a policy that specifies OPAT practices | 88.9% | 76.9% |

16 | The institute should track, record, review and report on antimicrobial use on a regular basis and if required report to national or state authorities | 88.5% | 83.3% |

17 | The Clinical Microbiology Diagnostic Laboratory must be in the close vicinity or preferably in the same hospital premises to reduce Specimen transportation time | 95.8% | 95.8% |

18 | The institute should have a fully functional 24×7 Clinical Microbiology Diagnostic Laboratory with competent manpower and signatory authority with Sunday and Holiday reporting | 91.7% | 92.0% |

19 | The institute should have guidance procedures for the right investigation, right patient and right time and must ensure the right report interpretation, right antimicrobial and right time | 91.3% | 91.7% |

20 | Clinical Microbiology Diagnostic Lab shall ensure that Lab Critical Alerts have been made and a Notification is sent each time any critical result is observed by the lab. | 96.0% | 95.8% |

21 | The Clinical Microbiology Laboratory should ensure that all proper protocols of Antimicrobial Susceptibility resting are being followed as per CLSI and or EUCAST. | 100% | 95.5% |

22 | Clinical Microbiology Diagnostic Lab should ensure The AMR Data Digitalization on WHONET | 91.7% | 95.8% |

23 | The institution should have documented Specimen Collection, Storage, Transportation and Processing Protocols and mandatory Culture Collection Protocol as the first specimen to be collected from the patient before the commencement of antimicrobials. | 91.7% | 95.7% |

24 | Even though Diagnostic Stewardship can be practised in the absence of Automation, However, the Institute must ensure that at least Automated Culture, Identification and Susceptibility equipment are present that provide MIC values | 95.5% | 95.5% |

25 | The institute should Ensure proper supply chain management is maintained so that there is no break in the Diagnostic Services. | 100% | 95.7% |

26 | The Lab must have a documented policy to communicate Preliminary Grams stain findings and reports and Test Interpretation must be communicated as early as possible | 95.7% | 95.5% |

27 | The laboratory must ensure that Clinical footnotes, interpretation, and knowledge dissemination on Intrinsic resistance are communicated in the report. | 90.9% | 95.5% |

28 | Wherever possible the lab should ensure that Personalized AST Reporting, Breakpoint to MIC Quotient based reporting is being performed especially in critically ill patients. | 91.3% | 90.9% |

29 | The institute should Ensure a Compulsory Induction Program for Post Graduate Residents, Interns on Diagnostic Stewardship regularly | 100% | 100% |

30 | The Clinical Microbiology Diagnostic lab should employ rapid diagnostic tests (RDT’s) molecular or phenotypic, for detecting resistance mechanisms so as to provide directed treatment | 100% | 95.7% |

31 | The institute should have a functional hospital infection control committee, with full-time appointed infection control officers and infection control nurses. | 100% | 100% |

32 | The institute should have a hospital infection control policy document | 100% | 100% |

33 | The institute should conduct HICC meetings regularly (e.g. monthly) | 100% | 95.5% |

34 | The institute should conduct a hand hygiene audit on a monthly basis at least in all critical areas. | 95.7% | 100% |

35 | The institute should conduct a biomedical waste segregation audit regularly. | 95.5% | 100% |

36 | The institute should conduct care bundle audits on a monthly basis at least in all critical areas. | 95.7% | 100% |

37 | The institute should conduct HAI surveillance on a monthly basis at least in all critical areas. | 95.7% | 100% |

38 | The institute should have a needle-stick injury prevention and management program through NSI surveillance. | 95.7% | 91.3% |

39 | The institute should have a policy that specifies adhering to adult vaccination by HCWs. | 95.7% | 91.3% |

40 | The institute should provide hepatitis B vaccine to all HCWs including the temporary staff and students and check anti-HB titers subsequently | 95.7% | 96.0% |

41 | The institute should perform environmental disinfection according to standard CDC/Kayakalp guidelines regularly | 95.5% | 95.2% |

42 | The institute should have a dynamic policy that specifies dealing with locally transmitted infections including MDRs. | 100% | 100% |

*Colour code for Practice Statements: Administrative- White, ASP- Green, DSP- Yellow, ISP- Orange.

Note: IAS – Integrated Antimicrobial Stewardship, HIC – Hospital Infection Control, ISP – Infection Stewardship Program, AMSP – Antimicrobial Stewardship Program, ASP – Antimicrobial Stewardship Program, DSP – Diagnostic Stewardship Program, MIC – Minimum Inhibitory Concentration, CLSI – Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, EUCAST – European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, AMR – Antimicrobial Resistance, WHONET – World Health Organization Network, SOP – Standard Operating Procedure, AST – Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing, CRE – Carbapenem-Resistant Enterobacterales, MRSA – Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus, ESBL – Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase, HAI – Healthcare-Associated Infection, NSI – Needle Stick Injury, HCWs – Healthcare Workers, HB – Hepatitis B, CDC – Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, NABH – National Accreditation Board for Hospitals, MDRs – Multidrug-Resistant Organisms, PK/PD – Pharmacokinetics/Pharmacodynamics, ID – Infectious Disease, DOT – Days of Therapy, AWaRe – Access, Watch, and Reserve (WHO classification of antibiotics), IV – Intravenous, OPAT – Outpatient Parenteral Antimicrobial Therapy, ADR/SAE – Adverse Drug Reaction/Serious Adverse Event

Following validation, each expert stated whether the specific practices were being followed in their institute. An average of their responses was taken if more than one expert belonged to the same institute. However, if several experts who agreed and disagreed were the same, it was considered a mixed response. Table 3 depicts the practices of various practice statements in the 31 institutes that participated in the study. It showed a varied response in different institutes. It was considered poor practice if <40% of the institutes practised a particular statement. One statement assessing the administrative practices stated that the institute should set accountability and responsibility on the pharmacologist/pharmacist to ensure rational antimicrobial use had poor practice compliance, with only 29.0% of the institutes practising this. The practices for statements assessing ASP ranged from 12.9% to 58.1%, with only four (12.9%) institutes having policies specifying outpatient parenteral antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) practices, which refers to the practice of administering intravenous antimicrobials to patients in an outpatient setting. DSP practices in these institutes ranged from 38.7% to 71.0%, with only 1 out of 14 statements having poor practices. This statement mentioned that the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory should ensure the digitalisation of AMR data on WHONET. The last 12 statements assessed ISPs, and their responses varied from 29.0% to 83.9%. Statement 42 stated that a dynamic policy that specifies dealing with locally transmitted infections should be put in place had poor compliance, with only 29.0%of institutes practising this. Practice Statement 31, which states that an institute should have a functional hospital infection control committee with full-time appointed infection control officers, had the most positive response, with 26 (83.9%) out of 31 institutes practising. One institute in Kerala was found to have the best practices, with 41 out of the 42 practice statements being followed

Table 3: Practices of various points in each institute | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Institute Code | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 32 | 33 | 34 | 35 | 36 | 37 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 42 | |

INST1 | P | M | N | M | M | N | M | N | P | M | N | N | N | P | N | N | M | N | M | M | P | N | M | P | M | N | P | M | N | M | P | P | M | P | P | N | P | M | M | M | P | N | |

INST2 | N | N | N | M | N | N | N | N | M | N | N | N | N | M | N | N | M | M | N | P | N | P | N | P | P | P | P | M | N | M | P | P | M | P | M | N | P | P | N | N | M | M | |

INST3 | N | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

INST4 | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | P | N | P | N | P | N | P | P | P | N | P | N | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | N | P | N | |

INST5 | N | N | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | N | N | N | P | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | P | P | N | N | P | N | N | P | N | P | N | P | |

INST6 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

INST7 | M | M | M | P | M | M | N | M | N | M | P | P | P | P | N | N | P | N | N | N | P | P | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | P | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | N | M | P | M | |

INST8 | P | P | P | P | M | P | P | P | P | P | M | P | – | P | M | M | P | M | M | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | M | P | P | M | P | P | M | P | P | P | |

INST9 | N | N | N | P | N | N | N | N | N | N | M | N | N | M | N | N | N | M | M | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | M | P | P | P | M | N | P | M | N | P | N | N | P | N | |

INST10 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

INST11 | P | P | N | P | N | N | N | N | P | N | N | N | N | P | N | N | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | N | N | P | P | N | N | P | N | |

INST12 | P | P | M | P | P | M | P | M | N | P | P | M | M | M | M | P | P | P | P | P | P | M | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | |

INST13 | P | – | P | – | N | N | N | – | – | P | N | P | P | P | N | P | P | P | N | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | |

INST14 | P | M | M | M | M | N | P | N | N | M | N | P | N | P | N | N | P | P | P | M | M | N | P | M | P | P | M | M | M | P | P | M | P | P | P | M | P | P | P | P | M | M | |

INST15 | N | N | N | P | N | N | N | N | N | – | P | P | N | P | – | – | P | – | – | P | P | N | P | – | P | N | P | – | – | P | P | P | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | P | – | – | |

INST16 | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | M | N | M | M | P | N | P | N | M | M | M | N | M | M | P | M | M | M | M | P | N | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | M | |

INST17 | P | P | P | P | M | M | P | N | N | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | N | N | P | – | N | N | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | P | P | – | P | – | – | – | P | – | P | – | – | |

INST18 | P | M | P | P | P | N | N | M | N | M | M | M | N | M | N | N | M | M | M | M | P | N | P | M | P | P | M | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | M | M | M | P | P | P | P | N | |

INST19 | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | N | N | P | P | P | P | N | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | N | N | N | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | N | P | N | |

INST20 | P | M | M | P | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | N | M | M | N | N | P | M | P | P | P | N | P | M | N | P | P | P | M | M | P | P | M | P | P | P | P | M | N | M | P | N | |

INST21 | P | P | P | P | N | N | N | N | N | P | P | P | P | N | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | N | |

INST22 | P | N | P | N | P | P | P | N | P | P | P | N | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | |

INST23 | P | P | P | – | N | P | P | N | N | P | P | N | N | N | N | P | P | P | N | P | P | N | N | P | P | P | N | N | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | |

INST24 | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | |

INST25 | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | N | P | P | N | N | P | N | N | P | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | |

INST26 | P | N | P | N | N | N | N | N | – | N | N | N | N | P | N | N | P | P | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | N | P | – | – | – | – | – | |

INST27 | P | P | N | P | N | P | P | N | N | P | P | P | N | P | N | P | P | P | N | P | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | N | P | P | N | P | N | P | N | |

INST28 | N | N | P | N | N | N | P | N | N | P | P | P | N | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | N | P | |

INST29 | P | P | P | P | N | P | – | P | P | – | P | P | P | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | |

INST30 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | – | P | N | N | P | N | N | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | N | P | N | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | N | |

INST31 | P | P | P | N | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | P | |

TOTAL | P | 20 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 5 | 7 | 13 | 15 | 14 | 9 | 18 | 4 | 10 | 21 | 15 | 13 | 19 | 22 | 12 | 18 | 17 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 26 | 23 | 17 | 22 | 20 | 14 | 22 | 22 | 13 | 17 | 20 | 9 |

N | 8 | 8 | 8 | 5 | 13 | 12 | 10 | 17 | 17 | 7 | 8 | 12 | 15 | 5 | 21 | 15 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 13 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 6 | 2 | 11 | |

M | 1 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 4 | |

– | 2 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 7 | |

Institutes which practice (in %) | 64.5 | 45.2 | 51.6 | 58.1 | 29.0 | 38.7 | 48.4 | 16.1 | 22.6 | 41.9 | 48.4 | 45.2 | 29.0 | 58.1 | 12.9 | 32.3 | 67.7 | 48.4 | 41.9 | 61.3 | 71.0 | 38.7 | 58.1 | 54.8 | 64.5 | 61.3 | 61.3 | 45.2 | 48.4 | 48.4 | 83.9 | 74.2 | 54.8 | 71.0 | 64.5 | 45.2 | 71.0 | 71.0 | 41.9 | 54.8 | 64.5 | 29.0 | |

Note: P=Practiced, N=Not Practiced, -=No response, M=Mixed results

Experts who say it is practised are equal to the experts saying it is not practised.

*Colour code for Practice Statements: Administrative- White, ASP- Green, DSP- Yellow, ISP- Orange.

*Practice points were (*Refer to Table 2 for detailed practice statements).

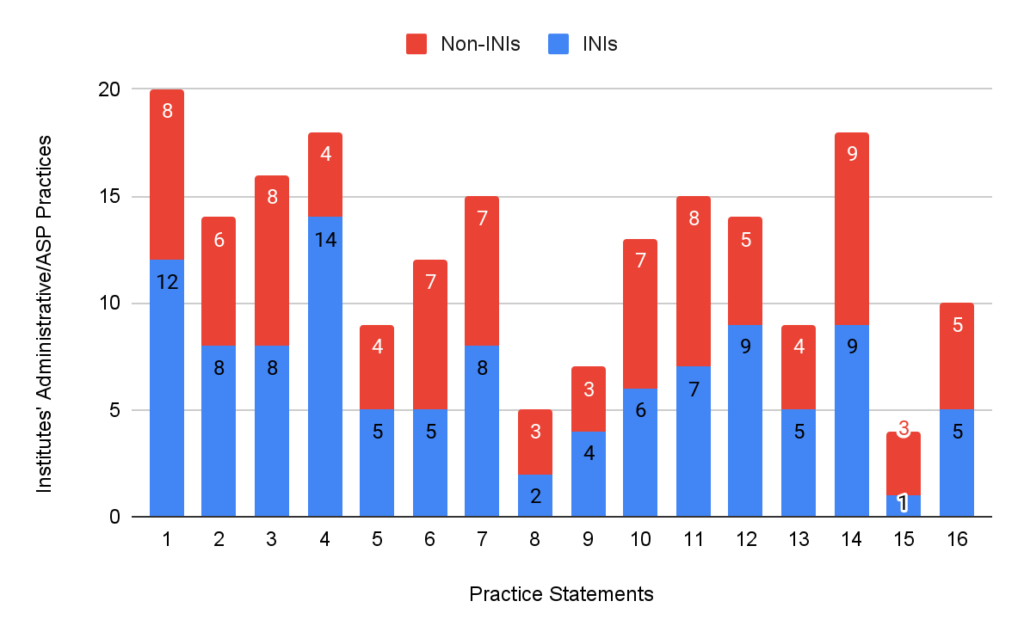

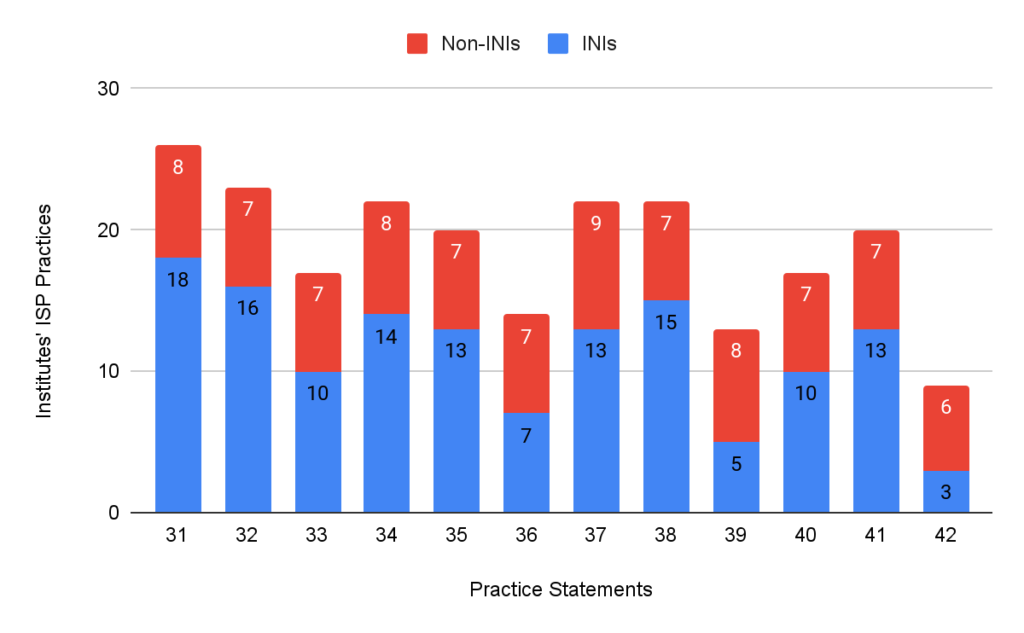

The differences in the practices of INIs and non-INIs have been shown in Figures 2, 3 and 4 for administrative/ASP, DSP, and ISP, respectively.

Only 44.8% of the INIs followed the administrative practices compared to 60% of the non-INIs. 26.4% of INIs and 55.5% of the non-INIs had ASP in place. 45.9% of the INIs and 74.3% of the non-INIs followed DSP. ISPs were in place in 54.3% of the INIs and 73.3% of non-INIs.

Figure 2: Practices followed by institutes’ administrative/ASP section.

*Practice points were (*Refer to Table 2 for detailed practice statements).

Figure 3: Practices followed by institutes’ DSP section.

Figure 4: Practices followed by institutes’ ISP section.

*Practice points were (*Refer to Table 2 for detailed practice statements).

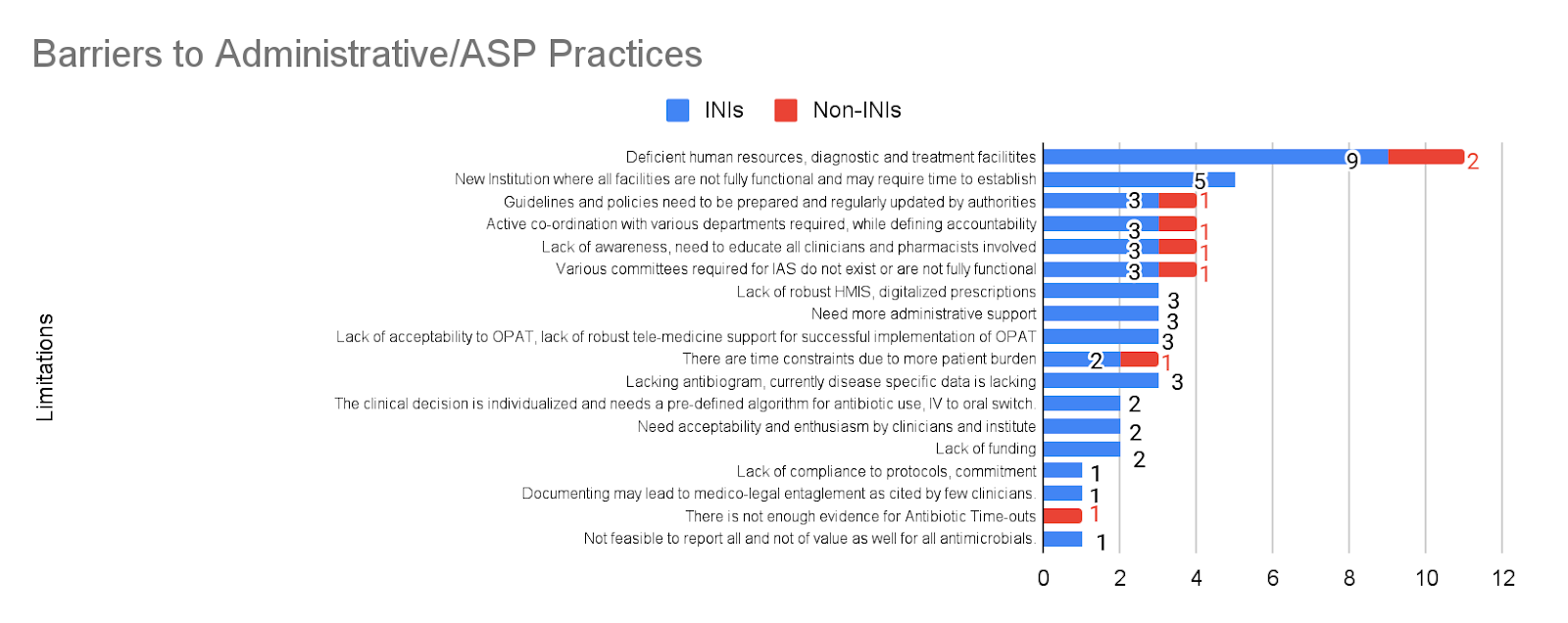

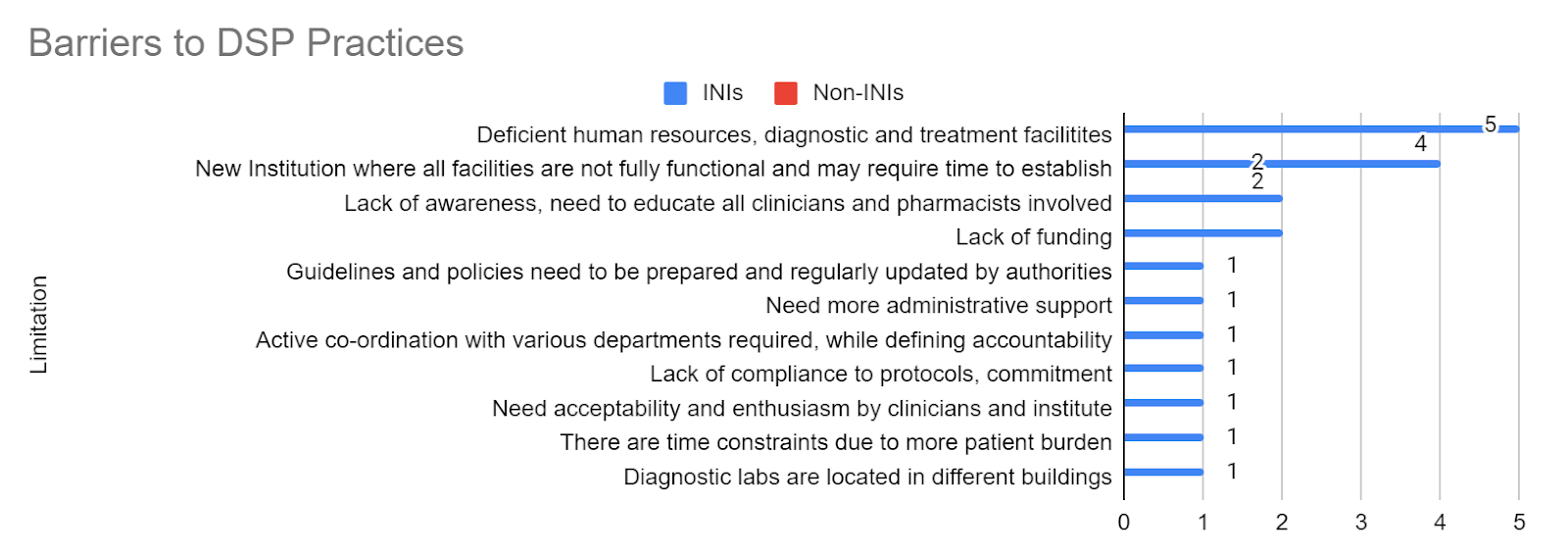

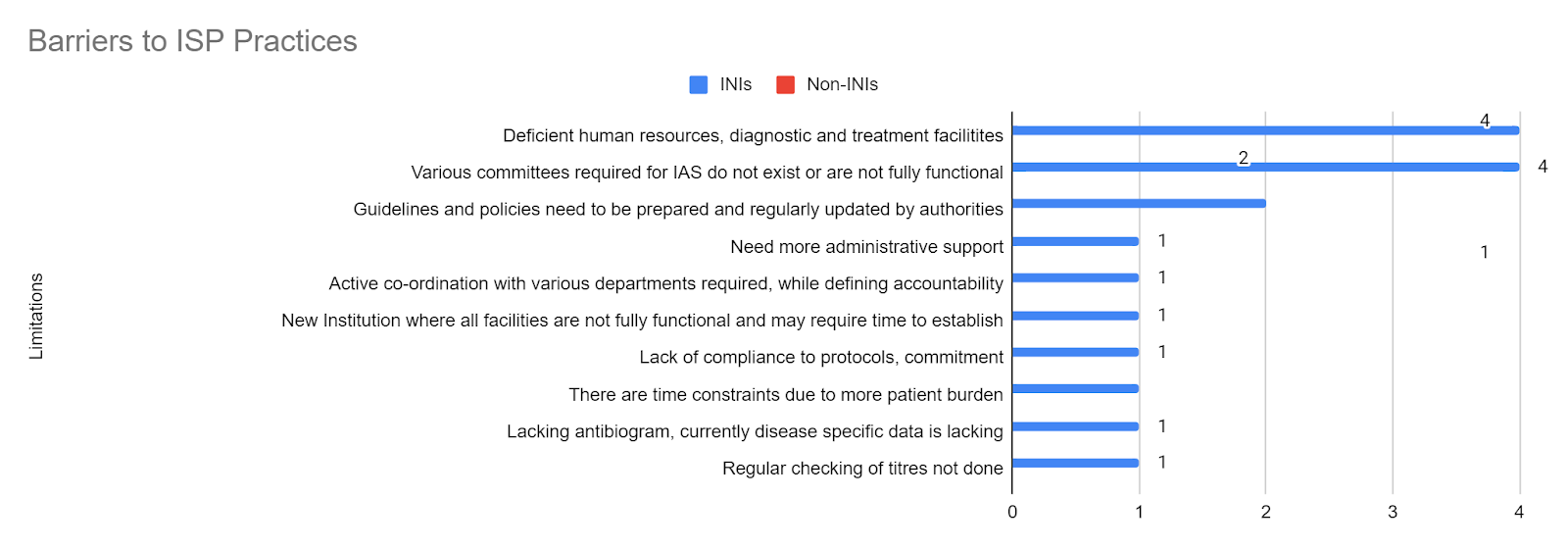

There were many barriers faced by the institutes’ IAS practising members (Figure 5). As stated by 13 institutes (41.9%), the most common limitation was a limited workforce and resources with a deficiency in the diagnostic and treatment facilities. This barrier stays consistent in all three categories of practices – administrative/ASP (35.5%), DSP (16.1%), and ISP (12.9%). This was followed by the issue that some of the institutes are new, where most facilities are not yet fully functional and may require time to establish full functionality. Details for the detailed limitations for administrative/ASP (Figure 6), DSP (Figure 7), and ISP (Figure 8) can be seen in the respective figures. Limitations have also been divided into barriers in INIs and non-INIs. The participants from non-INIs chose not to respond to obstacles related to DSP and ISP, which may be due to participation by non-HICC/AMSP members in these institutes. Some institutes believe that the practices of IAS require administrative support and extensive coordination with all the institute’s departments. Other limitations included a lack of acceptability of IAS practices among different departments, no available antibiogram areas, and a lack of time due to a significant patient burden.

Post-hoc analysis by phase 3 experts expanded questionnaire ‘The institute should Ensure a Compulsory Induction Program for Post Graduate Residents, Interns on Diagnostic Stewardship regularly’ to ‘The hospital should ensure a Compulsory Induction Program on diagnostic stewardship, good IPC & AMS practices for newly recruited Post Graduates, Interns, Junior Residents, Nurses, and other HCWs’ to advocate policy makers for IAS practices.

Figure 5: Various limitations, according to, experts in implementing IAS practices in Pan-India.

Figure 6: Various limitations, according to experts, to implementing IAS practices pan-India- Administrative/ASP Practices.

Figure 7: Various limitations according to experts to implementing IAS practices pan-India- DSP Practices.

Figure 8: Various limitations according to experts to implementing IAS practices pan-India- ISP Practices.

DISCUSSION

This Delphi-based study highlights IAS prevalence, implementation and gaps in Indian tertiary healthcare institutes, aiding efforts to combat AMR. Among the 44 responses from 31 healthcare institutes, 67.7% were INIs, with 61.4% of the respondents being members of their institutes’ HICC/AMSP members. INIs are autonomous, government-funded higher education institutes. Most experts agreed on the IAS practices for the Indian tertiary healthcare system, though substantial variations of practices exist across institutes. A lack of workforce and resources was the most notable limitation in following these practices. The consensus on the clarity and relevance of the practice statements indicates a shared understanding of the importance of antimicrobial stewardship, infection prevention, and diagnostic stewardship among healthcare professionals. However, the data also reveal significant discrepancies between awareness and implementation. This disparity suggests that while the theoretical framework for IAS is well-recognized, institutional constraints and logistical challenges impede its consistent application.

The experts’ experience ranged from 1 to 25 years, reflecting diverse awareness of institutional practices and inconsistencies in stewardship practices across institutes as less experienced professionals possibly encountered more challenges while implementing IAS practices. While 2/3rd of respondents were HICC/AMSP members, only 58.1% of participating institutes had such experts, which raises concerns about the remaining institutions, which may lack the necessary expertise policies to drive effective stewardship programs. This points to a potential gap in institutional capacity and underscores the need for more widespread involvement of trained personnel in stewardship initiatives.

One of the most striking findings is that less than two-thirds (64.5%) of institutions surveyed do not have an active IAS program. This lack of implementation is despite widespread acknowledgement of the necessity of stewardship in curbing antimicrobial misuse. The barriers to implementation, including insufficient infrastructure, lack of trained personnel, and the absence of regulatory frameworks, reflect broader systemic issues within the Indian healthcare system, particularly in newly established institutions that require additional time for setup and administrative organisation.

With over half the institutes lacking formal mechanisms to ensure compliance with IAS protocols, establishing effective IAS programs remains challenging despite 90% agreement on its importance. This finding suggests that while awareness of stewardship is relatively high, operationalising these programs remains a significant hurdle. Many institutions struggle to maintain momentum in addressing AMR without clear leadership and designated roles for overseeing stewardship efforts.7

Despite 88% of respondents recognising the importance of education, only 58.1% of institutes have active stewardship programs, highlighting the need for robust educational infrastructure to support prescribers, staff, and patients in understanding the impact of inappropriate antimicrobial use. By focusing on interactive learning, community engagement, integration into medical training, and continuous professional development, India can strengthen its response to AMR and foster a culture of responsible antibiotic use across all levels of healthcare.8-10 Given that newer institutions often lack the workforce and resources to develop and sustain educational initiatives, there is a pressing need for national policies that promote standardised training in antimicrobial stewardship across all healthcare settings. By ensuring consistent education, implementing evidence-based guidelines, fostering multidisciplinary collaboration, and raising public awareness, these policies can significantly improve the effectiveness of AMS efforts across all healthcare settings, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes and enhanced public health safety.11-12

Prescription review and audit systems were also identified as key gaps in stewardship practices, with only 48.4% of institutions conducting regular audits, despite most respondents’ acknowledgement of their importance. This finding is particularly concerning, as prescription audits ensure adherence to evidence-based guidelines and identify inappropriate antimicrobial use. These audits are essential in combating antimicrobial resistance by systematically evaluating prescribing practices, providing feedback, identifying training needs, and promoting continuous improvement.13,14 Many institutions’ lack of such systems may contribute to antibiotic overuse, further driving resistance.

A notable area for improvement is the implementation of pre-authorization and documentation practices for antimicrobial agents. Only 16.1% of institutions reported having pre-authorization systems, despite 82.8% supporting the practice. Similarly, PK/PD documentation, essential for optimising antibiotic dosing and minimising toxicity, is underutilised, with only 22.6% of institutions following this protocol. Resource constraints, administrative delays, and the need for formal stewardship guidelines likely contribute to these gaps.

When it comes to IV-to-oral switch practices, which are known to reduce hospital stays and associated healthcare costs, only 45.2% of institutions have adopted this strategy. The reluctance to implement this practice may be due to perceptions about antibiotic efficacy, operational challenges, hierarchical dynamics, patient-specific considerations, concerns about clinical stability, historical practices, and variability in clinical judgment.15,16

The study also highlights deficiencies in microbiology laboratory support for stewardship. Despite 71.0% of the institutions following international guidelines (CLSI or EUCAST) for antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST), less than 40% have adopted digitalisation tools such as WHONET to track AMR. Laboratories are critical in supporting stewardship programs by providing timely and accurate data on pathogen identification and resistance patterns, conducting susceptibility testing, facilitating rapid diagnostics, collaborating with antimicrobial stewardship teams, and guiding clinical decision-making.17-18 The underutilisation of these resources reflects broader challenges related to workforce shortages and outdated infrastructure.

Infection control measures, such as establishing HICC and regular audits of hand hygiene and biomedical waste management, are essential for preventing the spread of resistant organisms. While most institutions (95-100%) recognise the importance of these practices, regular audits and compliance remain suboptimal, with significant room for improvement in areas such as having policies specifically dealing with locally transmitted infections, adherence to adult vaccinations by HCWs, and conducting care bundle audits. Moreover, while certain practices, such as maintaining a functional HICC (83.4%), are more commonly implemented, other practices—like OPAT (12.9%)—are not prioritised in many institutions. This imbalance indicates the need for a more comprehensive approach to stewardship that ensures consistent implementation of all practices across settings. As seen in Figures 2, 3, and 4, practices were better in non-INIs compared to the INIs enrolled in the study. This could be because most INIs are relatively new institutes where the infrastructure and facilities are not fully developed yet, and there is a lack of exact reports from non-INIs due to non-HICC/AMSP experts.

The most frequently cited barriers to IAS implementation were resource limitations, including insufficient personnel, diagnostic capabilities, and treatment facilities, with over 40% of the institutes facing this issue. These findings are consistent with the broader challenges faced by healthcare systems in India, particularly in resource-constrained settings where infrastructure varies significantly between public and private sectors and urban and rural areas. Most of the experts from non-INIs were not members of their institutes’ AMSP/HICC committees, so they may not have complete knowledge of the barriers in their institutes, therefore opting not to answer the question. This could be the reason for the more significant obstacles to IAS practices in INIs, as shown in our study.

The study underscores the critical role of institutional leadership and administrative support in the success of IAS programs. Some experts emphasised the necessity of coordinated efforts across multiple departments, highlighting that stewardship practices cannot be the responsibility of an isolated team or department. A whole-system approach involving administration, clinicians, infection control teams, and diagnostics is essential for successfully integrating IAS practices. The variation in practice adoption across institutions suggests that IAS initiatives often suffer from fragmented implementation efforts, where only specific departments or personnel are fully engaged. One notable strength of this study is the involvement of multiple experts from institutions at various locations all over India, providing a comprehensive perspective on the state of IAS in India. However, the variability in responses across institutes also underscores the necessity for tailored strategies to address the specific challenges faced by different types of healthcare facilities. For instance, the successful practices observed at one of the institutes in Kerala suggest that models can be scaled and adapted to other institutions with similar challenges, albeit with appropriate adjustments to local resource availability and institutional constraints.

The study’s findings indicate that a top-down approach, wherein national or regional health bodies provide structured guidelines and a bottom-up commitment from institutional leadership, will be essential for adopting IAS practices. Policymakers must create robust frameworks for stewardship and provide the necessary resources and training to ensure effective implementation of these practices. The Delphi survey’s results serve as a reminder that IAS programs will only succeed when paired with adequate infrastructure, trained personnel, and administrative support.

Furthermore, the results of this study can serve as a foundation for future policy and practice improvements. SASPI body, comprising pan-India tertiary care affiliated institutes, is taking the lead in assessing time-to-time actual implementations of these 42 IAS practices. At the annual meeting (ASPICON) of SASPI, each representative institute member is asked to present their IAS practice data since 2018. SASPI aims to establish these practices in India but occasionally needs the government’s support and direction. There is an urgent need for a national-level strategy integrating stewardship practices into the broader healthcare ecosystem through the government of India and state governments. This should encompass creating a standardised national guideline for IAS, incentivising institutions to adopt these practices, and ensuring that resources are allocated to overcome the identified barriers. By implementing these measures, India can strengthen its response to the growing threat of AMR, which poses a significant public health risk.

This study has a few limitations that should be acknowledged. First, relying on a Delphi-based survey may introduce response bias, as institutions with more established stewardship practices may have been more likely to participate, and those with less developed practices may have been less likely to respond. However, taking pan-India institutes effectively balances these biases. Additionally, the study mainly focused on INIs, which may not fully represent all tertiary care institutions in India. Furthermore, the study’s cross-sectional nature only provides a snapshot of the current state of stewardship but does not capture trends over time. Furthermore, the study’s cross-sectional nature only provides a snapshot of the current state of stewardship but does not capture trends over time.

CONCLUSION

While this study demonstrates substantial agreement on the importance of IAS practices, we found a great need for awareness and action in many institutions in India. These 42 practice statements should be followed in all Indian tertiary care health systems. Each institute should track and monitor them regularly for improvisation of the observed lacunae. Overcoming these challenges will require sustained efforts from policymakers and healthcare institutions, focusing on resource allocation, training, and interdisciplinary collaboration through organisations like SASPI. With concerted action in a structured manner, using short-term, medium-term, and long-term strategies for addressing the barriers to IAS implementation, it can become an integral component of India’s healthcare system, thereby reducing the burden of AMR and improving patient outcomes nationwide.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

None

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The authors thank Ms Vinita Saini, SASPI office staff, for coordinating all SASPI-associated tertiary care hospitals to collaborate on the Delphi process.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

HS: Investigation; Methodology; Writing the draft

PKP: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Review

SP: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Review

SR: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Review

ASS: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Review

BS: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Review

AB: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Review

VT: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Review

IT: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Resources; Review

SASPI Consortium: Data collection; Analysis; Writing the draft

REFERENCES

WHO. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. Geneva: World Health Organization. Accessed December 25, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241564748

Knobloch MJ, McKinley L, Keating J, Safdar N. Integrating antibiotic stewardship and infection prevention and control programs using a team science approach. Am J Infect Control. 2021;49(8):1072-4.

Sharma A, Thakur N, Thakur A, Chauhan A, Babrah H. The Challenge of Antimicrobial Resistance in the Indian Healthcare System. Cureus. 2023;15(7):e42231.

Chauhan J, Chakraverty R, Pathan S. Antimicrobial stewardship program activities in India: an appraisal. International Journal of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 2022;11(6), 676–9.

Walia K, Ohri VC, Madhumathi J, Ramasubramanian V. Policy document on antimicrobial stewardship practices in India. Indian J Med Res. 2019;149(2):180-4.

Nasa P, Jain R, Juneja D. Delphi methodology in healthcare research: How to decide its appropriateness. World J Methodol. 2021;11(4):116-29.

ICMR. Antimicrobial stewardship program (AMSP) guidelines. New Delhi: Indian Council of Medical Research. Accessed December 25, 2024. https://main.icmr.nic.in/sites/default/files/guidelines/AMSP_0.pdf

Calò F, Onorato L, Macera M, et al. Impact of an Education-Based Antimicrobial Stewardship Program on the Appropriateness of Antibiotic Prescribing: Results of a Multicenter Observational Study. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(3):314.

Tahoon MA, Khalil MM, Hammad E, Morad WS, Awad SM, Ezzat S. The effect of educational intervention on healthcare providers’ knowledge, attitude, & practice towards antimicrobial stewardship program at, National Liver Institute, Egypt. Egypt Liver Journal. 2020;10:5.

Cisneros JM, Cobo J, San Juan R, Montejo M, Fariñas MC. Education on antibiotic use. Education systems and activities that work. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2013;31 Suppl 4:31-7.

Meher BR, Srinivasan A, Vighnesh CS, Padhy BM, Mohanty RR. Factors most influencing antibiotic stewardship program and comparison of prefinal- and final-year undergraduate medical students. Perspect Clin Res. 2020;11(1):18-23.

Silverberg SL, Zannella VE, Countryman D, et al. A review of antimicrobial stewardship training in medical education. Int J Med Educ. 2017;8:353-74.

MoHFW. Prescription audit guidelines. New Delhi: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Accessed December 25, 2024. https://nhsrcindia.org/sites/default/files/2021-07/1534_Prescription%20Audit%20Guidelines16042021.pdf

Singh T, Banerjee B, Garg S, Sharma S. A prescription audit using the World Health Organization-recommended core drug use indicators in a rural hospital of Delhi. J Educ Health Promot. 2019;8:37.

Ramirez JA, Vargas S, Ritter GW, et al. Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics and early hospital discharge: a prospective observational study of 200 consecutive patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(20):2449-54.

Ashiru-Oredope D, Attwood H, Cullum R, et al. Switching patients from IV to oral antimicrobials. Pharm J. 2023; 310(7972).

Luther VP The Essential Role of Clinical Microbiology Laboratories in Antimicrobial Stewardship. Washington DC: Associations for Diagnostics and Laboratory Medicine.Accessed December 25, 2024. https://www.myadlm.org/cln/articles/2015/august/stewardship

Chandra R. Facilitating antibiotic stewardship in the laboratory. Med Lab Observer Newsletter. 2024. Accessed December 25, 2024. https://www.mlo-online.com/disease/antibiotic-resistance/article/55131124/facilitating-antibiotic-stewardship-in-the-laboratory

*SASPI Consortium:

Meena Mishra1, Rahul Garg1, Deepjyoti Kalita2, Md Jamil2, Apurba Shastry3, Venkateswaran R3, Dineshbabu S3, Chinmoy Sahu4, Ujjwala Gaikwad5, Vinay R Pandit5, Binod Pati6, Prathyusha K6, Pramod Kumar Manjhi6, Puneet Kumar Gupta7, Harshita8, Prasan Kumar Panda8, Bhupinder Sholanky8, Deepa Kumari8, Maneesh Sharma8, Puneet Dhamija8, Manisha Bisht8, Rachna Rohilla9, Sivanantham Krishnamoorthi9, Deepak Kumar10, Vibhor Tak10, Sarita Mohapatra11, Sumit Rai12, Debabrata Dash12, Shyam Kishor Kumar13, Arkapal Bandyopdhyay14, Ujjala Ghoshal14, Arghya Das15, Iadarilang Tiewsoh16, Rahul Narang17, Ayush Gupta18, Sagar Khadanga18, Vivek Hada19, Shefali Gupta20, Sourabh Patro21, Ashish Behera21, Naveen M21, Moby Saira Luke22, Reena Anie Jose23, Neetu Mehrotra24, Poonam Sharma25, Lakshminarayana Sa26, Sandhya Bhat K27, Deepashree R28, Roopali Somani29, Pragnya Paramita Jena30, Niyati Trivedi31

Affiliations:

|

|

|

Submit a Manuscript:

Copyright © Author(s) 2024. JASPI- Journal of Antimicrobial Stewardship Practices and Infectious Diseases.