A Rare Case of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Pyomyositis in a Patient with Chronic Granulomatous Disease

JASPI December 2025 / Volume 3 /Issue 4

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Sikdar S, Priyadarshi M, Aggarwal K, et al.A Rare Case of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Pyomyositis in a Patient with Chronic Granulomatous Disease. JASPI. 2025;3(4)26-30 DOI: 10.62541/jaspi100

ABSTRACT

A 40-year-old male with uncontrolled diabetes presented with anterior chest wall and right thigh swelling. CT imaging revealed a superficial abscess in the chest wall and a multiloculated pus collection in the subcutaneous and intermuscular planes of the right gluteus and quadriceps, consistent with pyomyositis. Pus cultures grew MRSA. Immunological workup identified chronic granulomatous disease, indicating defective NADPH oxidase function in leukocytes. The patient was treated with targeted antibiotics and surgical incision and drainage. Following six weeks of antibiotic therapy, he was discharged in stable condition with appropriate prophylaxis to prevent recurrence.

KEYWORDS: Pyomyositis; Methicillin resistant; Chronic granulomatous disease; Abscess

INTRODUCTION

Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD) is a primary immunodeficiency disorder characterised by recurrent bacterial or fungal abscesses in macrophage-rich organs like lymph nodes, liver, lung, or recurrent skin infections. CGD is rare, with an incidence of 1 in 250,000 births in the United States. It arises due to mutations resulting in defective nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, leading to impaired production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the phagolysosome membrane, which in turn results in the impaired killing of microorganisms by neutrophils and macrophages.1

Pyomyositis is predominantly a disease of the tropical areas; it goes by many names around the world, such as tropical pyomyositis, myositis tropicans, but of late, it is being reported from temperate regions of the world as well. It is seen more commonly in children and in young adults with a male: female ratio of 1.5:12 Pyomyositis is a rare presentation of CGD, and there are only 2 reported cases of pyomyositis complicating CGD3,4. We report such an unusual case of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) pyomyositis in an immunosuppressed male who was later diagnosed to have underlying CGD.

CASE PRESENTATION

A 40-year-old gentleman presented to the emergency department with pain and swelling in the anterior chest wall and right hip and thigh for the past 6 months. He was a known case of type 1 diabetes mellitus for the last 10 years, on insulin therapy. The history was significant for multiple emergency visits due to recurring superficial abscesses requiring drainage in the last 4years. For his multiple emergency visits, the surgeon would drain the pus and discharge him on oral antibiotics. The patient could not furnish any reports of cultures sent or antibiotics given. He did not complain of fever or any other systemic symptoms. There was no family history of recurrent infections or immunodeficiency. Physical examination on admission revealed a temperature of 37.5°C, pulse rate of 109 beats/minute, blood pressure of 112/84mm Hg, respiratory rate of 18 breaths/minute, and oxygen saturation of 98% (room air). On ultrasound, a subcutaneous collection was present in the chest, suggestive of a superficial abscess, which was subsequently drained.

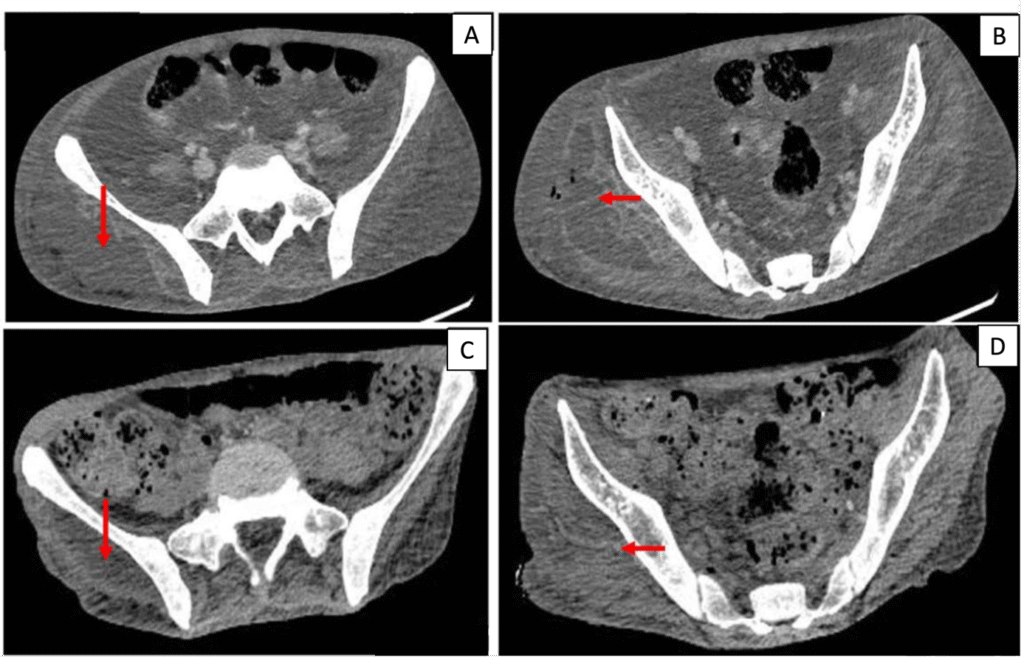

Blood investigations showed a hemoglobin of 9.4g/dl and mild leukocytosis with a total leukocyte count of 11.5 x10^9/uL. Renal and hepatic functions were within normal limits. Inflammatory markers were not available. Blood sugar was uncontrolled with an HbA1C of 11.2%. He was started on insulin infusion, which was later converted to a subcutaneous basal bolus regimen and titrated according to blood sugar monitoring. 2 sets of blood cultures were sent on admission before starting of antibiotics. Contrast-enhanced computer tomography (CECT) of the abdomen and lower limbs showed a multiloculated fluid collection in the subcutaneous plane and inter-muscular plane of the gluteus and quadriceps muscles with erosions in the femoral head and acetabular, suggestive of pyomyositis, although there was no evidence of osteomyelitis. (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Contrast-enhanced CT (CECT) axial images at presentation (A, B) and during follow-up after treatment (C, D). (A, B) Multiloculated hypodense collections in the subcutaneous and intermuscular planes of the right gluteal and proximal thigh musculature (arrows), consistent with pyomyositis, with adjacent soft-tissue inflammation. (C, D) Interval reduction in the size and extent of the collections following surgical drainage and targeted antimicrobial therapy.

Incision and drainage of pus from the right thigh were performed, and culture of the pus yielded methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Antimicrobial susceptibility testing by the Kirby–Bauer disc diffusion method, interpreted according to CLSI disc diameter cutoffs.5 demonstrated susceptibility to trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX), clindamycin, linezolid, teicoplanin, vancomycin, and rifampicin. The same organism was also isolated from the blood cultures.. The patient was started on linezolid 600mg BD. The duration of the antibiotic was increased to 6 weeks in view of dissemination of infection. Regular wound dressing and pus drainage were done. Given the history of recurrent abscesses, the patient was evaluated for primary immunodeficiency disorders (PID). Tests for hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and antibodies against HIV-1/2 and HCV were negative.

Primary immunodeficiency (PID) workup showed a reduced CD4:CD8 ratio and decreased NADPH oxidase activity was determined by nitro-blue tetrazolium testing. , suggestive of chronic granulomatous disease (CGD). Other PID workup like evaluation for T-cell defects (Interferon-γ, Interleukin-12 levels), B-cell defects (X- Linked agammaglobulinemia, Common Variable Immunodeficiency, Selective IgA Deficiency), phagocytic defects (Leucocyte Adhesion Defects), complement (early and late complement defects) and combined immunodeficiencies (Wiscott-Aldrich Syndrome, Adenosine deaminase (ADA) deficiency, Ataxia telangiectasia, DiGeorge Syndrome) were negative.

In accordance with the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommendations for the management of Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD), the patient was discharged on lifelong prophylaxis with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole and itraconazole, and received immunizations against influenza, pneumococcus, and hepatitis B prior to discharge.

DISCUSSION

Pyomyositis, a primary suppurative infection of skeletal muscles, traditionally prevalent in tropical areas, is now emerging in temperate regions due to heightened awareness and improved diagnostic methods6. Trauma has been reported in approximately 20–50% of pyomyositis cases and is thought to predispose to infection by facilitating bacterial invasion into deep muscle tissue. However, in a substantial proportion of patients, no evident portal of entry is identified, suggesting that occult bacteremia may play a role in pathogenesis.7

Predisposing factors of pyomyositis are immunosuppression, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, chronic lung or kidney diseases, immunosuppressive drugs, intravenous drug abuse, and HIV infection8.

Clinically, such patients typically present with muscle pain, fever, local swelling and redness, and back pain. There are 3 distinct stages of presentation of the disease, namely stage 1, the invasive stage, stage 2, the suppurative stage, and stage 3, the late disseminated stage9. Pyomyositis is often detected late in its course because of unawareness of this condition and non-specific clinical presentation, leading to increased mortality in patients.

CGD usually manifests as inflammation the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, eyes, and urogenital tract10. It was previously known as “a fatal granulomatous disease of childhood,” but with advances in early diagnosis, imaging modalities, and antimicrobial prophylaxis and treatment, there has been a marked decline in mortality11. CGD results from a defect in the nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase enzyme complex of phagocytes, impairing their ability to generate a respiratory burst and produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anion (O₂⁻), hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), hypochlorite (HOCl), and hydroxyl radical (OH⁻), which are essential for intracellular killing of pathogens12.

The NADPH oxidase complex consists of five major subunits: the membrane-bound components gp91phox and p22phox, encoded by the CYBB and CYBA genes respectively, and three cytosolic factors—p47phox, p67phox, and p40phox—encoded by NCF1, NCF2, and NCF46. Mutations in CYBB (located on chromosome Xp21.1) lead to the X-linked recessive form of CGD, whereas defects in the autosomal genes result in autosomal recessive variants of the disease13. These genetic abnormalities compromise oxidative killing by neutrophils and macrophages, predisposing affected individuals to recurrent and often severe bacterial and fungal infections. Staphylococcus aureus is the most frequently isolated pathogen, while gram-negative organisms such as Klebsiella, Salmonella, Serratia, and Aerobacter species are also commonly implicated. In addition, infections caused by Burkholderia and Nocardia species have been reported, and Aspergillus remains one of the predominant causes of invasive fungal disease in patients with CGD14.

Diagnostic evaluation of CGD is based on assays assessing neutrophil oxidative burst, including direct superoxide measurement, cytochrome-c reduction, chemiluminescence, nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) reduction, and dihydrorhodamine (DHR) 123 flow cytometry. A low CD4:CD8 ratio is not diagnostic of CGD — it is a nonspecific finding that can occur due to chronic/recurrent infections and immune activation. The true diagnostic hallmark of CGD remains demonstration of impaired oxidative burst (via DHR assay or NBT test) and genetic confirmation of NADPH oxidase complex mutations.

The standard management of Chronic Granulomatous Disease (CGD) involves both prophylactic and therapeutic use of antibacterial and antifungal agents to prevent life-threatening infections. Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole remains the first-line antibacterial prophylactic agent and has been shown to markedly reduce infection rates. For patients with sulphonamide allergy, alternatives such as dicloxacillin or ciprofloxacin may be considered. Antifungal prophylaxis with itraconazole is generally well tolerated and effective in preventing invasive fungal infections, particularly due to Aspergillus species. Additional therapeutic options include adjunctive interferon-γ, which enhances phagocyte microbicidal activity, and curative approaches such as hematopoietic stem cell transplantation and emerging gene therapy modalities15, 11.

Immunization is a critical preventive measure, as CGD patients can mount adequate humoral and cellular immune responses. The IDSA and CDC recommend annual inactivated influenza vaccination, pneumococcal vaccination (PCV13 followed by PPSV23), and hepatitis B vaccination before discharge or during follow-up to ensure optimal protection against secondary infections16, 17.

Management of MRSA bacteremia demands immediate source control and initiation of targeted antimicrobial therapy. Vancomycin remains the first-line antibiotic of choice for MRSA bacteremia and endocarditis when the isolate exhibits a vancomycin MIC≤2 g/mL. Daptomycin, ceftaroline, linezolid and combination therapy are alternative options in cases of persistent MRSA bacteremia or bacteremia caused by vancomycin intermediate Staphylococcus aureus (VISA) or vancomycin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (VRSA)13.

Pyomyositis is a rare presentation of CGD, with very few cases reported in the literature. To date, only two cases of CGD presenting with pyomyositis have been documented. The first involved a known CGD patient who developed Enterobacter cloacae pyomyositis of the quadriceps, as described by Goussef et al4. The second case, reported by Camanni et al., described Aspergillus myofasciitis in a child with CGD who was not receiving itraconazole prophylaxis3. In the present case, the diagnosis of CGD was established incidentally at a later age, prompted by clinical suspicion following a protracted and atypical presentation. This underscores the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for primary immunodeficiencies, including CGD, in patients presenting with recurrent or unusual infections, as early recognition is key to appropriate management and improved outcomes.

The increasing recognition of pyomyositis in diverse climates stresses the significance of timely diagnosis and intervention for this potentially severe condition, where understanding its epidemiology is crucial for effective management and prevention in both tropical and temperate zones.

Learning point for clinicians:

Pyomyositis can be a rare presentation of chronic granulomatous disease (CGD).

It is important to screen for CGD and other immunodeficiency disorders in patients presenting with unprovoked deep tissue abscesses.

Early diagnosis of primary immunodeficiency disorder helps in the timely initiation of appropriate prophylactic therapy to prevent recurrence of infection.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the personnel of our outpatient clinic, including nurses, doctors, and residents. No funding was received for this research paper.

DECLARATIONS

ETHICAL APPROVAL

A written informed consent was obtained from the patient. (It has been attached with the supplementary material). This is a case report and no approval from the AIIMS research ethics committee was required.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of manuscript. The authors have no financial and non-financial interests to disclose.

DISCLOSURE

There are no competing interests related to the authors of this manuscript.

FUNDING

No funding was received to assist with the preparation of the manuscript. The authors have no financial and non-financial interests to disclose.

REFERENCES

Justiz-Vaillant AA, Williams-Persad AFA, Arozarena-Fundora R, Gopaul D, Soodeen S, Asin-Milan O, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease (CGD): commonly associated pathogens, diagnosis and treatment. Microorganisms. 2023 Sep 5;11(9):2233.

DermNet New Zealand. Tropical pyomyositis [Internet]. Auckland: DermNet NZ; 2023 [cited 2025 Oct 18]. Available from: https://dermnetnz.org/topics/tropical-pyomyositis

Camanni G, Sgrelli A, Ferraro L. Aspergillus myofasciitis in a chronic granulomatous disease patient: first case report. Infez Med. 2017 Sep;25(3):270–3.

Gousseff M, Lanternier F, Ferroni A, Chandesris O, Mahlaoui N, Hermine O, et al. Enterobacter cloacae pyomyositis complicating chronic granulomatous disease and review of gram-negative bacilli pyomyositis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013 Jun;32(6):729–34.

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) [Internet]. Wayne (PA): CLSI; [cited 2025 Aug 30]. Available from: https://clsi.org/

Agarwal V, Chauhan S, Gupta RK. Pyomyositis. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2011 Nov;21(4):975–83.

Crum NF. Bacterial pyomyositis in the United States. Am J Med. 2004 Sep 15;117(6):420–8.

Tanabe A, Kaneto H, Kamei S, Hirata Y, Hisano Y, Sanada J, et al. Case of disseminated pyomyositis in poorly controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus with diabetic ketoacidosis. J Diabetes Investig. 2016 Jul;7(4):637–40.

Scharschmidt TJ, Weiner SD, Myers JP. Bacterial pyomyositis. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2004 Oct;6(5):393–6.

Marciano BE, Spalding C, Fitzgerald A, Mann D, Brown T, Osgood S, et al. Common severe infections in chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2015 Apr 15;60(8):1176–83.

Winkelstein JA, Marino MC, Johnston RB Jr, Boyle J, Curnutte J, Gallin JI, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease: report on a national registry of 368 patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000 May;79(3):155–69.

Dinauer MC. Chronic granulomatous disease and other disorders of phagocyte function. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2005:89–95.

Roos D, de Boer M. Molecular diagnosis of chronic granulomatous disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 2014 Feb;175(2):139–49.

Segal BH, Leto TL, Gallin JI, Malech HL, Holland SM. Genetic, biochemical, and clinical features of chronic granulomatous disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2000 May;79(3):170–200.

Holland SM. Chronic granulomatous disease. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2013 Feb;27(1):89–99.

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) [Internet]. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2025 [cited 2025 Jan 21]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/index.html

Marciano BE, Rosenzweig SD, Kleiner DE, Anderson VL, Darnell DN, Anaya-O’Brien S, et al. Gastrointestinal involvement in chronic granulomatous disease. Pediatrics. 2004 Aug;114(2):462–8.

Submit a Manuscript:

Copyright © Author(s) 2025. JASPI- Journal of Antimicrobial Stewardship Practices and Infectious Diseases.