Cutaneous Diphtheria: An Overlooked Skin and Soft Tissue Infection – A Case Series from India

JASPI December 2025 / Volume 3 /Issue 4

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Vadivoo N S, Usha B, Sudh K.Cutaneous Diphtheria: An Overlooked Skin and Soft Tissue Infection – A Case Series from India.JASPI. 2025;3(4)19-25

DOI: 10.62541/jaspi107

ABSTRACT

Cutaneous diphtheria is an under-recognised manifestation of an infection which is caused by Corynebacterium diphtheria (C. diphtheriae) and particularly in endemic regions. Usually it presents as a chronic non-healing ulcer and is frequently polymicrobial origin, which may lead to misidentification as contamination. In this article, we have reported four cases of cutaneous diphtheria, including one toxigenic strain with severe clinical progression and three non-toxigenic strains associated with diabetic foot ulcers. Diagnosis of this condition was established through careful Gram stain examination, culture reports, and confirmatory testing using MALDI-TOF or PCR with Elek’s test. Recognising the condition at an early stage is important for appropriate antimicrobial therapy, infection control, and prevention of transmission. In this case series, we have highlighted the continued relevance of cutaneous diphtheria in India, where underreporting remains a concern.

KEYWORDS: Cutaneous diphtheria, Corynebacterium diphtheriae; Chronic ulcers; Polymicrobial infection

INTRODUCTION

Cutaneous diphtheria has been recognized worldwide as a rare infectious disease, and it was documented since 1759 1, 2. Both toxic 3, 4, 5 and non-toxic 6, 7 strains of Corynebacterium diphtheria cause skin manifestation which can lead to cutaneous diphtheria. Clinically, it is characterised by progressive non-healing necrotic, persistent ulcer that commonly affect the limbs. Overcrowding 1, 2, low socioeconomic status 4, travel to endemic locations 8, 19, 11, 12, skin trauma 8, 9, pre-existing skin lesions, immunocompromised status, and contact with livestock and pets13 are some of the various risk factors that were linked to the disease. In many cases an immunocompromised state can be due to a long-term diabetes mellitus 7, 11 and that is a major risk factor for infection by opportunistic pathogens such as C. diphtheriae.

Symptomatic infections with non-toxigenic strains of C. diphtheriae are rare but, when identified, need appropriate treatment. Due to contagious nature and prolonged shedding from chronic skin lesions it is very important to control the infection, otherwise it may contaminate the environment and spread to susceptible individuals 7-8, 12, 25. Few case reports have been published in India 3-7 and a considerable number of publications from other developing countries and reports following travel to endemic areas from developed countries 1, 2, 9, 12, 15, 17, 18, 20-25. This lower number of reports from India may be due to various factors, including neglect of this pathogen as a skin commensal or growth masked by polymicrobial infection.

In this article we have reported four cases of Cutaneous Diphtheria among which one case is due to toxigenic strain with bad prognosis. Other three strains are isolated from diabetic patients with chronic non-healing foot ulcer.

CASE SERIES

CASE 1

Demographics and comorbidities:

A 55-year-old male presented to the surgery outpatient department with a history of a chronic non-healing ulcer over the left leg for 10 years. He was a known case of chronic kidney disease for 5 years and was hemodynamically stable.

Cutaneous Lesion characteristics:

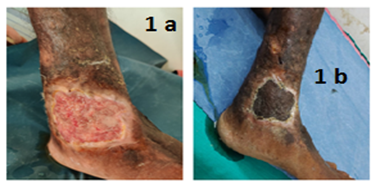

The ulcer measured 6 × 5 × 2 cm and was located over the left medial malleolus, with membranous slough (Figure 1a).

Microbiological findings:

Culture of exudate obtained from the depth of the ulcer showed polymicrobial growth of Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Morganella morganii. C. diphtheriae was presumptively identified based on colony morphology on blood agar, Gram stain, and Albert’s stain (Table 1).

Antimicrobial susceptibility (AST) of Diphtheria isolate shown in Table 2 was performed as per EUCAST Standardized disc diffusion method & zone Break points interpreted as per EUCAST 2019 v.9.0 guideline. Morganella morganii (AST was performed as per CLSI guideline ) susceptible to amikacin, cefepime, ciprofloxacin, and cotrimoxazole based on zone size Interpretation as per CLSI 2022 guideline. Throat swab culture showed no evidence of pharyngeal carriage of C. diphtheriae.

Confirmation of Corynebacterium diphtheriae : The isolate was confirmed as a non-toxigenic strain of C. diphtheriae by MALDI-TOF at a reference laboratory (Coimbatore).

Treatment and outcome:

The patient was treated with intravenous ciprofloxacin and cefepime for two weeks along with daily wound care and then he underwent split-skin grafting, and a significant wound healing was observed on follow-up (Figure 1b).

Figure: 1a &1b Chronic leg ulcer of case-1 (Before & after SSG)

CASE 2

Demographics and comorbidities:

A 40-year-old male presented with swelling over the left eye and forehead for four days and swelling of the right eye for one day. He had sustained a traumatic injury to the left eye eight days earlier. He had no history of diabetes mellitus or tuberculosis and was hemodynamically stable.

Cutaneous Lesion characteristics:

Examination revealed diffuse periorbital swelling, sloughing of the left eyelid with purulent discharge, facial skin excoriation, conjunctival chemosis, and palpable left submandibular lymph nodes (Figure 1 c).

Fig-1 c: Fulminant orbital & frontal cellulitis (Case-2)

Microbiological findings:

Culture of pus from the affected site showed polymicrobial growth of Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Streptococcus pyogenes. C.diphtheriae was presumptively identified by colony morphology, Gram stain, and Albert’s stain (Table 1). Antimicrobial susceptibility is detailed in Table 2. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Diphtheria isolate shown in Table 2 was performed as per EUCAST Standardized disc diffusion method & zone Break points interpreted as per EUCAST 2019 v.9.0 guideline. S. pyogenes (AST performed as per CLSI guideline) was susceptible to Penicillin, Ampicillin, and Clindamycin based on zone size Interpretation as per CLSI 2022 guidelines.

Confirmation of Corynebacterium diphtheriae : The isolate was confirmed as a toxigenic strain of C. diphtheriae by PCR and Elek’s test at Christian Medical College, Vellore.

Treatment and outcome:

The patient received intravenous cefoperazone–sulbactam for seven days, ciprofloxacin for six days, and topical mupirocin. Due to fulminant clinical progression, he was referred to a higher ophthalmic center before confirmatory results were received. Follow-up could not be obtained.

CASE 3

Demographics and comorbidities: A 70-year-old female presented with a left leg ulcer of 15 days’ duration. She was a newly diagnosed case of diabetes mellitus and had no history of tuberculosis. Vital signs were stable.

Cutaneous Lesion characteristics: The ulcer measured 6 × 3 × 2 cm and was located on the anterior aspect of the middle third of the leg. The ulcer was foul-smelling, covered with slough, and infested with maggots (Figure 1 d).There was no radiological evidence of osteomyelitis.

Fig-1 d : Leg ulcer (Case-3)

Microbiological findings: Culture report shows polymicrobial growth of C. diphtheriae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Proteus mirabilis. C. diphtheriae was presumptively identified by standard staining and culture characteristics (Table 1).Antimicrobial susceptibility is shown in Table 2 was performed as per CLSI guideline for broth dilution and zone Break points interpreted as per CLSI 2023 MIC Breakpoint. The accompanying Gram-negative isolates were susceptible to cefepime, piperacillin–tazobactam, gentamicin, and carbapenems based on zone size Interpretation as per CLSI 2023 guidelines

Confirmation of Corynebacterium diphtheria : The isolate was confirmed as a non-toxigenic strain of C. diphtheriae at Christian Medical College, Vellore.

Treatment and outcome: The patient was treated with intravenous cefotaxime for two days and discharged on request with advice for wound care and oral antibiotics.

CASE 4

Demographics and comorbidities: A 65-year-old male with hypertension and poorly controlled diabetes mellitus presented with right leg ulcers of 10 days’ duration following minor trauma.

Cutaneous Lesion characteristics: Two ulcers were present: one measuring 4 × 3 × 2 cm over the right medial malleolus and another measuring 3 × 3 × 2 cm over the anterior aspect of the right foot. Both ulcers had serous discharge, warmth, tenderness, and maggot infestation (Figure 1 e).

Fig-1 e: Chronic leg ulcer of Case-4(Before Wound debridement)

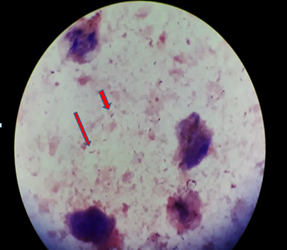

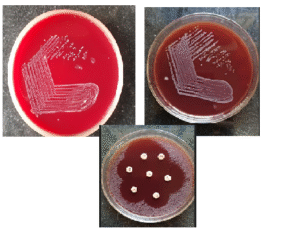

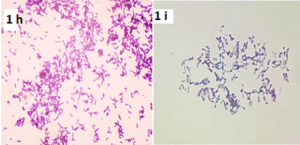

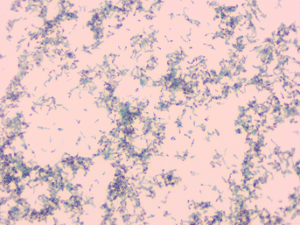

Microbiological findings: Tissue bit samples from both ulcers showed pure growth of Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Presumptive identification was based on Gram stain, Albert’s stain, and colony morphology (Table 1; Figures 1 f-j). Antimicrobial susceptibility is detailed in Table 2 was performed as per CLSI guideline for broth dilution & interpreted as per CLSI 2023 MIC Breakpoint.

Figure-1 f –Direct Gram stain –Case 1

Figure-1 g: Colony growth on Blood agar and AST on Blood Agar

Figure 1 h & i: Colony Gram staining

Figure-1 j: Colony Alberts stain

Confirmation of Corynebacterium diphtheriae : The isolate was confirmed as a non-toxigenic strain of C. diphtheriae at Christian Medical College, Vellore.

Treatment and outcome: The patient received intravenous ceftriaxone for five days along with surgical debridement and regular wound care. Marked wound healing was observed on follow-up (Figure 1 k).

Figure-1 k : Chronic leg ulcer of Case-4(after Wound debridement)

Table-1: Results of Microbiological Investigation

Case | Direct Gram stain Findings | Culture Characteristics | Microscopic / Special Stain findings | Culture Confirmation (Method and Lab) |

Case 1 | Many pus cells, Moderate epithelial cells, Few Gram-Positive bacilli and Gram-negative bacilli | Small greyish -white, non-haemolytic colonies on blood agar1 | Gram stain: Gram positive bacilli with clubbed ends arranged in V and L forms 2 Albert Stain: Green bacilli with bluish-purple metachromatic granules arranged in V and L forms 3 | Non toxigenic diphtheriae confirmed by MALDI-TOF. Reference laboratory, Coimbatore |

Case 2 | Many pus cells, Few epithelial cells, Moderate Gram-Positive bacilli and Gram-positive cocci in chains | Growth resistant with C. Diphtheriae on blood agar | Gram stain and Albert stain consistent with C.Diphtheriae morphology | Toxigenic C.Diphtheriae confirmed by PCR AND Elek’s test. Department of Microbiology, CMC Vellore |

Case 3 | Many pus cells, few epithelial cells, few Gram positive bacilli and moderate Gram-negative bacilli | Polymicrobial growth including C.Diphtheriae | Gram stain and Albert stain consistent with C.Diphtheriae | Non-Toxigenic C.Diphtheriae confirmed by PCR AND Elek’s test. Department of Microbiology, CMC Vellore |

Case 4 | Many pus cells, no epithelial cells, few Gram positive bacilli and Occasional Gram positive cocci in pairs | Pure growth of C.Diphtheriae | Gram stain and Albert stain consistent with C.Diphtheriae | Non-Toxigenic C.Diphtheriae confirmed by PCR AND Elek’s test. Department of Microbiology, CMC Vellore |

Footnotes

Figure 1 g: Colony morphology on blood agar

Figures 1 h & 1i: Gram stain showing club-shaped bacilli in V and L arrangement

Figure 1 J: Albert stain showing metachromatic granules

Note:

*PCR : Polymerase chain reaction

**CMC : Christian Medical college-Vellore

TABLE-2: Antibiotic susceptibility of Diphtheria isolates (EUCAST 2019 zone Break points * and CLSI 2023 MIC Breakpoint **)

R-Resistant, S-Susceptible

Diphtheria isolate | Penicillin | Erythromycin | Clindamycin | Tetracycline | Ciprofloxacin | Linezolid | Vancomycin |

Isolate-1* (Cse-1) | R | S | T | S | S | S | S |

Isolate 2* (Case 2) | R | S | S | S | S | S | S |

Isolate 3** (Case 3) | R | S | S | R | S | S | S |

Isolate 4** (Case 4) | S | S | S | S | S | S | S |

Infection Control Measures: Following presumptive identification of C. diphtheriae, all patients were isolated, and appropriate droplet precautions were implemented to prevent transmission.

DISCUSSION

Diphtheria is a re-emerged public health concern in several regions, including resource-rich settings, with a notable rise in both respiratory and cutaneous forms over the past decade1, 2, 13, 23, 25. Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Corynebacterium ulcerans are the commonest reported causative agents of cutaneous Diphtheria. Respiratory diphtheria is the commonest and severe clinical form. The recent increasing reports of cutaneous diphtheria highlight its significance epidemiologically6,7,10–25. Cutaneous diphtheria usually presents as non-specific, chronic ulcers, commonly involving in the extremities and frequently developing at sites of prior skin trauma, as observed in Cases 2 and 4 of the present series 8,9,13.

Multiple risk factors can cause the development of cutaneous diphtheria, which includes diabetes mellitus, skin trauma, poor wound hygiene, overcrowding, and compromised socioeconomic conditions. In our case series, diabetes mellitus was the commonest predisposing factor. This highlights the role of diabetes mellitus in impairing host defenses and facilitating opportunistic infection. Microbiologically it was reported that cutaneous diphtheria is often polymicrobial, with C. diphtheriae isolated alongside other bacterial pathogens. Streptococcus pyogenes and Staphylococcus aureus are commonly reported co-pathogens, but in our case series we have observed a predominant Gram-negative co-infection, and this highlights the regional and clinical variability 4,10–14,18–20,22,24,25. Particularly, one case in this series yielded a pure isolate of C. diphtheriae, highlighting that monomicrobial infection can occur and should not be overlooked.

Both toxigenic and non-toxigenic strains of C. diphtheriae are capable of causing cutaneous infection. Although systemic complications are uncommon with cutaneous disease, toxigenic strains may be associated with severe local disease and poor outcomes, as illustrated by the fulminant clinical course in one patient in this series. Importantly, non-toxigenic strains are not clinically benign; they can cause persistent infection, delay wound healing, and serve as reservoirs for prolonged bacterial shedding, thereby posing infection-control challenges. Factors such as migration, poverty, overcrowding, and geopolitical conflicts particularly in settings with poor hygiene—continue to facilitate the persistence and re-emergence of cutaneous diphtheria worldwide 1,2,4,10,19.

CONCLUSIONS

Among patients with chronic non-healing ulcers, particularly in those with diabetes or a history of trauma Cutaneous diphtheria should be considered. A thorough microbiological evaluation should be done for Gram-positive bacilli instead of dismissing them as contaminants. Early diagnoses, appropriate antimicrobial therapy, along with strict infection-control measures are essential to prevent transmission and complications.

IEC APPROVAL

This study got IEC approval & Number is AMCH/IEC/Proc.No.56/2024 Dated 17-4-24.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We are immensely grateful to the faculty of the concerned clinical departments for referring clinical samples for microbiological investigations and for sharing relevant clinical details. We also sincerely thank our colleagues and technical staff of the Department of Microbiology for their invaluable support.

I extend my heartfelt gratitude to our retired Senior Professor, Dr. Suhasini Chawda, who sensitized us to the possibility of Corynebacterium diphtheriae infection in superficial wounds and chronic non-healing ulcers.

We also thank the Department of Microbiology, Christian Medical College (CMC), Vellore, for their assistance in the confirmation and toxigenicity testing of the Corynebacterium diphtheriae isolates.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Authors declare no conflict of interests

SOURCE OF FUNDING

None

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

NS V: Conceptualization, Supervision and Guidance, Review and editing , Data collection and sorting, Analysis, Writing draft

BU: Conceptualization, Review and editing

KS: Conceptualization, Review and editing , Data collection

REFERENCES

Livingood CS, Perry DJ, Forrester JS. Cutaneous diphtheria: a report of 140 cases. J Invest Dermatol. 1946 Dec;7(6):341-364. doi:10.1038/jid.1946.42.

Koopman JS, Campbell J. The role of cutaneous diphtheria infections in a diphtheria epidemic. J Infect Dis. 1975 Mar;131(3):239-244. doi:10.1093/infdis/131.3.239

Chaturvedi VN, Lulay SN, Kaitkey SK. Nasal and cutaneous diphtheria. Indian J Otolaryngol. 1977;29:34-35. doi:10.1007/BF03047877.

Pandit N, Yeshwanth M. Cutaneous diphtheria in a child. Int J Dermatol. 1999 Apr;38(4):298-299. doi:10.1046/j.1365-4362.1999.00658.x.

Shenoy S, Prashanth HV, Wilson G. A case of cutaneous and pharyngeal diphtheria. Indian Pediatr. 2002 Mar;39(3):311-312.

Govindaswamy A, Trikha V, Gupta A, Mathur P, Mittal S. An unusual case of post-trauma polymicrobial cutaneous diphtheria. Infection. 2019 Dec;47(6):1055-1057. doi:10.1007/s15010-019-01300-x.

Singla P, Mane P, Singh P. Cutaneous diphtheria by nontoxigenic Corynebacterium diphtheriae in a diabetic patient: a case report. J Clin Diagn Res. 2021 Apr;15(4):DD01-DD03.

Berih A. Cutaneous Corynebacterium diphtheriae: a traveller’s disease? Can J Infect Dis. 1995 May;6(3):150-152. doi:10.1155/1995/646325.

Cassir N, Bagnères D, Fournier PE, Berbis P, Brouqui P, Rossi PM. Cutaneous diphtheria: easy to be overlooked. Int J Infect Dis. 2015 Apr;33:104-105. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2015.01.008.

FitzGerald RP, Rosser AJ, Perera DN. Non-toxigenic penicillin-resistant cutaneous Corynebacterium diphtheriae infection: a case report and review of the literature. J Infect Public Health. 2015 Jan-Feb;8(1):98-100. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2014.05.006.

Batista Araújo MR, Bernardes Sousa MÂ, Seabra LF, Caldeira LA, Faria CD, Bokermann S, et al. Cutaneous infection by non-diphtheria-toxin producing and penicillin-resistant Corynebacterium diphtheriae strain in a patient with diabetes mellitus. Access Microbiol. 2021 Nov;3(11):000284. doi:10.1099/acmi.0.000284.

Abdul Rahim NR, Koehler AP, Shaw DD, Graham CR. Toxigenic cutaneous diphtheria in a returned traveller. Commun Dis Intell Q Rep. 2014 Dec;38(4):E298-E300.

Levi LI, Barbut F, Chopin D, Rondeau P, Lalande V, Jolivet S, et al. Cutaneous diphtheria: three case reports to discuss determinants of re-emergence in resource-rich settings. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2021 Dec;10(1):2300-2302. doi:10.1080/22221751.2021.2008774.

Rappold LC, Vogelgsang L, Klein S, Bode K, Enk AH, Haenssle HA. Primary cutaneous diphtheria: management, diagnostic workup, and treatment exemplified by a rare case report. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016 Jul;14(7):734-736. doi:10.1111/ddg.12722.

Alberto C, Osdoit S, Villani AP, Bellec L, Belmonte O, Schrenzel J, et al. Cutaneous ulcers revealing diphtheria: a re-emerging disease imported from Indian Ocean countries? Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2021 Mar;148(1):34-39. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2020.04.024.

Wollina U, Bitel A, Neubert F, Koch A. Localized cutaneous non-toxic diphtheria (case report). Georgian Med News. 2019 Apr;(289):114-116.

Menier L, Bourgea E, Otto MP, Dutasta F, Morand JJ, Janvier F. Cutaneous diphtheria in a patient just returned from Tahiti. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022 Dec;28(12):1591-1593. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2022.01.018.

Griffith J, Bozio CH, Poel AJ, Fitzpatrick K, DeBolt CA, Cassiday P, et al. Imported toxin-producing cutaneous diphtheria—Minnesota, Washington, and New Mexico, 2015–2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019 Mar;68(12):281-284. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6812a2.

Kolios AGA, Cozzio A, Zinkernagel AS, French LE, Kündig TM. Cutaneous Corynebacterium infection presenting with disseminated skin nodules and ulceration. Case Rep Dermatol. 2017 May;9(2):8-12. doi:10.1159/000476054.

Morgado-Carrasco D, Riquelme-McLoughlin C, Fustá-Novell X, Fernández-Pittol MJ, Bosch J, Mascaró JM Jr. Cutaneous diphtheria mimicking pyoderma gangrenosum. JAMA Dermatol. 2018 Feb;154(2):227-228. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2017.4786.

Nelson TG, Mitchell CD, Sega-Hall GM, Porter RJ. Cutaneous ulcers in a returning traveller: a rare case of imported diphtheria in the UK. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2016 Jan;41(1):57-59. doi:10.1111/ced.12763.

Placke JM, Chapot V, Sondermann W. Primary cutaneous diphtheria as a rare cause of infectious ulceration. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020 Dec;117(51-52):888. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2020.0888b.

Marshall NC, Baxi M, MacDonald C, Jacobs A, Sikora CA, Tyrrell GJ. Ten years of diphtheria toxin testing and toxigenic cutaneous diphtheria investigations in Alberta, Canada: a highly vaccinated population. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022 Jan;9(1):ofab414. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofab414.

Trubin M, Eichinger SE, Abraham A, et al. A rare case of locally contracted cutaneous Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Cureus. 2023 Jun;15(6):e40854. doi:10.7759/cureus.40854.

Lowe CF, Bernard KA, Romney MG. Cutaneous diphtheria in the urban poor population of Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: a 10-year review. J Clin Microbiol. 2011 Jul;49(7):2664-2666. doi:10.1128/JCM.00272-11.

Submit a Manuscript:

Copyright © Author(s) 2025. JASPI- Journal of Antimicrobial Stewardship Practices and Infectious Diseases.