Prevalence and Risk Factors of Clostridioides difficle Infection over a Period of Two Years in a Tertiary Care Hospital - a Retrospective Study

JASPI December 2025 / Volume 3 /Issue 4

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Muthiah V, Jayapalan A, Murugesa M.Prevalence and Risk Factors of Clostridioides difficle Infection over a Period of Two Years in a Tertiary Care Hospital – a Retrospective Study. JASPI. 2025;3Page No

DOI: 10.62541/jaspi099

ABSTRACT

Background: Clostridioides difficile is a spore-forming Gram-positive anaerobic bacillus and an important cause of healthcare-associated diarrhea. It ranges in severity from mild diarrhea to pseudomembranous colitis, toxic megacolon, and sepsis. Although CDI has been widely studied in developed countries, limited data are available from South India, particularly Tamil Nadu.

Objectives: This study aimed to (i) estimate the prevalence of CDI among symptomatic patients, (ii) assess associated risk factors, and (iii) evaluate the relationship between broad-spectrum antibiotic use and CDI.

Methods: A retrospective observational study was conducted at a tertiary care hospital in Madurai between January 2021 and December 2022. All liquid stool samples submitted for CDI testing were included, excluding duplicates. Samples were screened using a qualitative immunochromatographic assay for glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) and toxins A/B. Data were analyzed using SPSS; categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, while continuous variables were reported as mean ± SD.

Results: Out of 330 stool samples tested, 55 (16.6%) were positive for CDI. Males comprised 56.4% of cases. The majority of them belong to the pediatric age group (25.5%) between 2 and 12 years. Most patients were admitted under Hemato-oncology (58.2%) and ICUs (25.4%). Prior proton pump inhibitor use was reported in 92.7%. 78.2% had malignancy or were receiving immunosuppressive therapy. The mean hospital stay was 19.73 ± 13.24 days. Meropenem (61.8%) and third-generation cephalosporins (34.5%) were the most frequently used antibiotics, with meropenem significantly associated with CDI (p=0.001). Nearly half (49.1%) developed CDI within one week of antibiotic initiation. Clinical outcomes showed 76.4% discharged in good condition, while 7.3% mortality occurred predominantly among patients with hematological malignancy. Treatment most commonly involved oral vancomycin plus metronidazole (56.3%), followed by metronidazole monotherapy (30.9%).

Conclusion: The prevalence of CDI in our center was 16.6% in 2021-22. Major risk factors included antibiotic exposure, PPI use, malignancy, and immunosuppression. Meropenem was most strongly associated with CDI. While combination therapy was frequently prescribed, vancomycin monotherapy remains the standard of care. These findings highlight the burden of CDI in one of the Southern India healthcare facilities.

KEYWORDS: Clostridioides difficile; Meropenem; Malignancy; Oral vancomycin

INTRODUCTION

Clostridioides difficile is a spore-forming Gram-positive anaerobic bacillus which is ubiquitous in nature. It exists as normal flora of the gut in around 2% of healthy individuals(1). The risk factors leading to Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) are antibiotic usage, immunocompromised state, age, severe comorbidities, prolonged hospitalization, usage of PPIs, those with altered gut flora due to surgeries or chemotherapy. CDI has markedly increased following the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics in general clinical practice(2). Ampicillin, Amoxicillin, Cephalosporins, Clindamycin and Tetracycline are commonly involved in Antibiotic-associated CDI worldwide(6).

The CDC definition of CDI is defined by the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms with either a stool test positive for toxigenic C. difficile or a histopathological or colonoscopic evidence of pseudomembranous colitis(3). It presents with a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations ranging from mild-to-moderate diarrhea to the more severe pseudomembranous colitis, toxic megacolon and sepsis. It is also notorious for causing large outbreaks in health-care facilities and severe epidemics contributed by the hypervirulent strains(2). The pathogenicity of C. difficile is mediated by two endotoxins: toxin A (TcdA) and toxin B (TcdB).

CDI is a serious healthcare-associated infection (HAI) now being increasingly reported from hospitals across India. Although CDI has been well studied in developed countries, there is a paucity of data regarding C. difficle-associated diarrhea in South India, especially in South Tamil Nadu where there are no studies to our knowledge. Hence, this study aims to estimate the prevalence of CDI and identify risk factors associated with it among symptomatic diarrheal patients attending a tertiary care hospital.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This was a retrospective observational study conducted at a tertiary care hospital in Madurai from January 2021 to December 2022. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC E-059, dated 12.06.2023). Clinical suspicion of CDI arises in patients with recent antibiotic use, hospitalization, or other risk factors, who present with symptoms such as diarrhea (≥3 unformed stools per day), abdominal pain, and fever. All stool samples tested for suspected CDI during the study period were included for data analysis. Duplicate samples were excluded from the study.

The toxigenic culture (TC) is considered the gold standard technique to determine Clostridioides difficile infection. This method involves the culture and isolation of C. difficile from fecal samples, followed by toxin testing of the isolate.

All liquid stool samples are screened for C. difficile glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) and Toxin A & B using Qualitative Immunochromatographic assay. CerTest (BIOTEC) Clostridioides difficile GDH+Toxin A+B one step combo card test is a coloured chromatographic, lateral flow immunoassay for the simultaneous qualitative detection of Clostridioides difficile Glutamate Dehydrogenase (GDH), Toxin A and Toxin B in stool samples. Stool collection tube with the specimen is shaken well and three drops of it is dispersed in each circular window marked as A (GDH), B(Toxin A) and C (Toxin B). Results read at 10 minutes and interpreted according to manufacturer’s instructions(16) provided in the kit insert. The control lines (green band) are internal controls, which confirm sufficient specimen volume and correct procedural technique. The test lines appear as the red coloured bands if positive and no band appears if negative. Total absence of any control green coloured line regardless the appearance or not of the test lines are considered invalid.

CDI is defined as cases in which patients tested positive for both GDH and toxins A or B. Sepsis markers such as CRP, Procalcitonin, and LDH were tested in patients following the development of symptoms such as fever or loose stools, and the corresponding data were collected from clinical case sheets.

The collected data were entered into Microsoft Excel, and frequency distributions were calculated. The point prevalence of CDI among the samples tested during the study period was estimated. Data entry and analysis were performed using SPSS software. Continuous variables were presented as means and standard deviations (SD), whereas categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

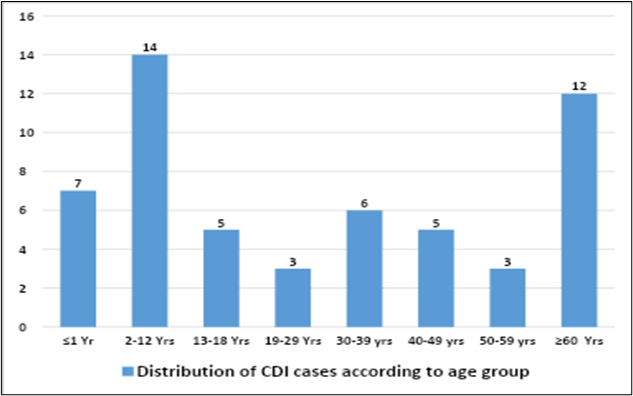

A total of 330 stool samples were screened for Clostridioides difficile. Out of 330 samples, 55 (16.6%) were positive for CDI. There were 31 (56.4%) male and 24 (43.6%) female patients. Approximately 25.5% of CDI patients belonged to the pediatric age group (2–12 years), while 21.8% were 60 years or older (Figure-1). Among the total CDI cases, 32 patients (58.2%) were admitted to the Haemato-Oncology Department, and 14 patients (25.4%) were admitted to the Intensive Care Units (ICUs).

Figure-1: Age wise distribution of CDI

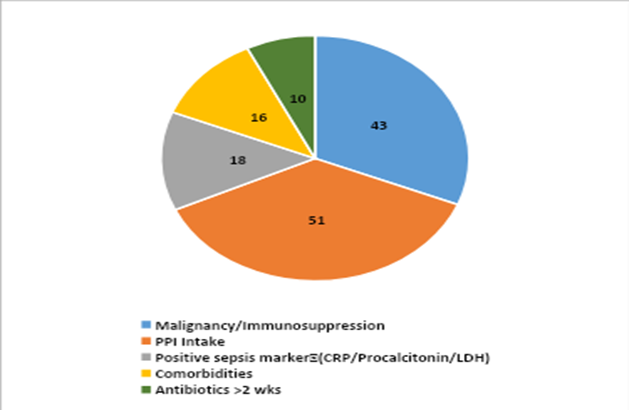

Most patients (92.7%) had used proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) prior to the development of infection, and 78.2% had malignancy or were on immunosuppressive therapy. Positive sepsis markers such as CRP, Procalcitonin, and LDH were seen in 32.7% of patients. The mean hospital stay was 19.73 ± 13.24 days. Meropenem (61.8%) was the most frequently used antibiotic, followed by third-generation cephalosporins (34.5%) in patients with CDI (p = 0.001).

Figure-2: Risk factors associated with CDI

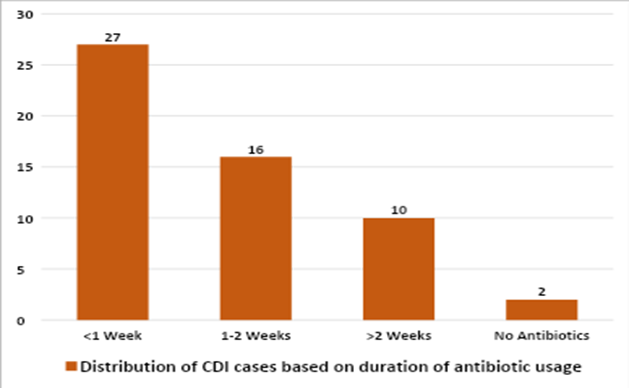

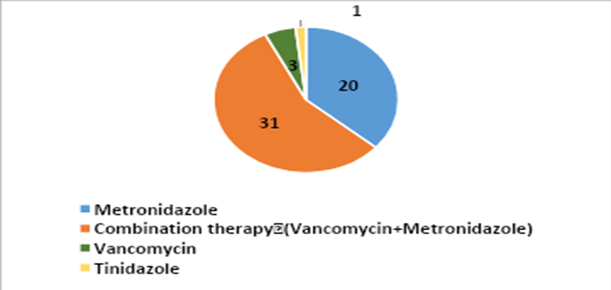

Nearly 27 patients (49.1%) developed CDI within one week of starting antibiotic therapy (Table-1), and 16 patients (29.1%) developed CDI within 1–2 weeks of antibiotic therapy (Figure-3). Out of 55 patients, 42 (76.4%) were discharged in good condition, while 4 patients (7.3%) expired during treatment. Among the four patients who died, three were diagnosed with hematological malignancy, and one was undergoing treatment for deep thermal burns with sepsis and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS). Regarding treatment for CDI, combination therapy (oral vancomycin 10 mg/kg every 6 hours + oral metronidazole 7.5 mg/kg every 8 hours) was used in 31 patients (56.3%), followed by metronidazole monotherapy in 20 patients (36.3%). The duration of treatment varied between 7–10 days, depending on the clinical resolution of symptoms.

Figure-3: Distribution of patients based on duration of antibiotic usage prior to onset of CDI

Figure 4: Treatment of CDI

ANTBIOTICS | No. of patients | PERCENTAGE |

MEROPENEM | 34 | 61.80% |

FLUOROQUINOLONES | 9 | 16.30% |

CEPHALOSPORINS(3RD GEN) | 19 | 34.50% |

PIPERACILLIN-TAZOBACTAM | 12 | 21.80% |

CEFOPERAZONE-SULBACTUM | 4 | 7.00% |

AMOXICILLIN CLAVULANATE | 1 | 1.80% |

CEFTAZIDIME AVIBACTAM | 2 | 4.00% |

CLINDAMYCIN | 2 | 4.00% |

AZITHROMYCIN | 4 | 7.00% |

COLISTIN | 5 | 9% |

TIGECYCLINE | 11 | 20% |

TEICOPLANIN | 16 | 29% |

TRIMETHOPRIM-SULPHAMETHOXAZOLE | 12 | 21.80% |

Table-1: Frequency of antibiotic usage among CDI positive patients

DISCUSSION

Clostridioides difficile remains the most important healthcare-associated cause of diarrhea among adults in the United States. In developing countries like India, the prevalence of CDI is largely underestimated. The prevalence rate of CDI in our study was 16.6%, which is comparable to the findings of Kannabath et al (2) from South India, who reported prevalence of 18%. In contrast, a lower prevalence rate of 9.1% was observed in a study conducted in Saudi Arabia by Abdulhakeem et al.

CDI is commonly associated with the older age group (>60 years), mainly due to multiple comorbidities and more frequent hospital visits (9). In our study, the majority of CDI cases were seen in the pediatric age group of 2–12 years (25.5%), followed by the age group ≥60 years (21.8%). Most of the patients (58.2%) were admitted to the Hemato-oncology department, and 25.4% of patients were admitted to the ICU.

The C. difficile–infected patients comprised 56.4% males and 43.6% females, which is in concordance with many Indian studies that showed male predominance (7). Patients with a history of PPI intake (92.7%) and malignancy/immunosuppression (78.2%) were found to have a higher prevalence of CDI than those with other risk factors such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, systemic illness, and positive sepsis markers in our study. Acid suppressant use prior to the development of CDI was the major risk factor associated with CDI in a study by Abdulhakeem et al. (9), whereas in a study by Bhatawadekar et al., comorbidities were the most common associated risk factor (10). A potential explanation for the association between PPI usage and CDI could be that the vegetative forms of C. difficile, which are acid-sensitive, survive and bypass the stomach, playing a role in CDI pathogenesis (11). The United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has also issued a warning about the possible association between gastric acid suppression therapy with PPIs and CDI (12).

Antibiotic usage is a well-recognized risk factor for CDI, as prolonged use can disrupt the normal gastrointestinal flora, thereby reducing the body’s natural defense mechanisms against infection (10). In our study, 18.2% of patients had received antibiotics for more than two weeks before developing CDI, while the majority (78.2%) had received them for less than two weeks. These findings are comparable to those reported by Singhal et al. (1), where more than half of the study population with CDI had a history of antibiotic exposure for less than two weeks.

According to Table 1, among the broad-spectrum antibiotics used, Meropenem (61.8%) was most frequently associated with CDI development in our study (p = 0.001 in t-test, which is statistically significant), followed by third-generation cephalosporins (34.5%). In a study by Rafey et al. (13), the antibiotics most commonly associated with CDI were Piperacillin–Tazobactam, followed by Meropenem.

LIMITATION OF THE STUDY

The key limitation of the study is the diagnosis of CDI was based on a qualitative immunochromatographic assay for GDH and toxins A and B without confirmation by toxigenic culture or molecular methods such as PCR, which may have led to under or overestimation of the true prevalence. In addition, antimicrobial susceptibility testing was not performed and therefore antibiotic resistance patterns of C. difficile could not be evaluated.

COLCLUSIONS

Based on our study findings, the prevalence of CDI in our hospital was 16.6%. The major risk factors identified were antibiotic and proton pump inhibitor use, followed by malignancy and immunosuppression. Meropenem emerged as the antibiotic most significantly associated with CDI. Combination therapy with vancomycin and metronidazole was the most commonly used treatment, showing favorable clinical outcomes; however, drug resistance was not assessed in this study. Hence, there is a need to incorporate preventive measures in healthcare settings to prevent this HAI.

ETHICAL PERMISSION

Approved by Institutional ethical committee, Meenakshi mission hospital and research centre. Letter Number: E-059

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

None

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

Authors declare no conflict of interests

SOURCE OF FUNDING

None

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

VM: Conceptualization, Supervision and Guidance, Review and editing

AJ: Data collection and sorting, Analysis, Writing draft

MM: Data collection, Supervision and Guidance

REFERENCES

Singhal T, Shah S, Tejam R, Thakkar P. Incidence, epidemiology and control of Clostridium difficile infection in a tertiary care private hospital in India.IJMM.2018 Jul-Sep;36(3):381-384.

Kannambath R, Biswas R, Mandal J, Vinod KV, Dubashi B, Parameswaran N. Clostridioides difficile Diarrhea: An Emerging Problem in a South Indian Tertiary Care Hospital. JLP.2021 Jul 9;13(4):346-352.

Cohen S H, Gerding D N, Johnson S,Kelly C P,Loo V G, McDonald L C et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults:SHEA and IDSA .2010;31(05):431–455.

Eze P, Balsells E, Kyaw M H, Nair H. Risk factors for Clostridium difficile infections – an overview of the evidence base and challenges in data synthesis. JOGH.2017;7(01):10417.

Alalawi M, Aljahdali S, Alharbi B, Fagih L, Fatani R, Aljuhani O. Clostridium difficile infection in an academic medical center in Saudi Arabia: Prevalence and risk factors. ASM .2020;40:305–9.

Banawas SS. Clostridium difficile infections: a global overview of drug sensitivity and resistance mechanisms. BioMed Research International.2018;8414257.

Ghia CJ, Waghela S, Rambhad GS. Systematic Literature Review on Burden of Clostridioides difficile Infection in India. JCP.2021;14:2632010X211013816.

Abdulhakeem Althaqafi, Adeeb Munshi. The prevalence, risk factors, and complications of Clostridium difficile infection in a tertiary care center, western region, Saudi Arabia.JIPH.2022.1037–1042 .

Alzouby S, Baig K, Alrabiah F, Shibl A, Al-Nakhli D, Senok AC. Clostridioides difficile infection: Incidence and risk factors in a tertiary care facility in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.JIPH.2020;13(7):1012-1017.

Bhatawadekar SM, Yadav LS, Babu A, Modak MS. Antibiotic-Associated Clostridium difficile Diarrhoea in Tertiary Care Hospital – A Study from Western India. JPAM.2023;17(3):1471-1476.

Tleyjeh IM, Abdulhak AB, Riaz M,Garbati MA,Tannir MA,Alasmari FA et al. The association between histamine 2 receptor antagonist use and Clostridium difficile infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE.2013;8(3):e56498

Howell MD, Novack V, Grgurich P, Soulliard D, Novack L, Pencina M et al. Iatrogenic gastric acid suppression and the risk of nosocomial Clostridium difficile infection. Arch Intern Med. 2010 ,May 10;170(9):784-90.

Rafey A, Jahan S, Farooq U, Akhtar F, Irshad M, Nizamuddin S et al. Antibiotics Associated With Clostridium difficile Infection. Cureus. 2023, May 15;15(5):e39029.

McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Bakken JS, Carroll KC, Coffin SE et al. Clinical practice guidelines for Clostridium difficile infection in adults and children: 2017 update by the infectious diseases society of America (IDSA) and society for healthcare epidemiology of America (SHEA). CIDS.2018;66:e1-e48.

National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE).Clostridium difficile infection: risk with broad-spectrum antibiotics. Published: 17 March 2015.Available from www.nice.org.uk/guidance/esmpb1

Submit a Manuscript:

Copyright © Author(s) 2025. JASPI- Journal of Antimicrobial Stewardship Practices and Infectious Diseases.