MICs of Ciprofloxacin, Cefuroxime, and Amikacin among Escherichia coli. Urinary Isolates: An AMR Study

JASPI September 2025 / Volume 3 /Issue 3

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Vardhan H, Eerike M, S R, et al.MICs of Ciprofloxacin, Cefuroxime, and Amikacin among Escherichia coli Urinary Isolates: An AMR Study JASPI. 2025;3(3):9-14 DOI: 10.62541/jaspi081

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Escherichia coli (E. Coli) poses a mounting threat to public health. The efficacy of ciprofloxacin (a fluoroquinolone), cefuroxime (a cephalosporin), and amikacin (an aminoglycoside) is increasingly undermined by emerging resistance.The study was conductedto evaluate susceptibility patterns and minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) trends for ciprofloxacin, cefuroxime, and amikacin in E. Coli urinary isolates at a tertiary care centre over a four-month period.

Methods: This retrospective observational study analysed antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) reports from the Microbiology Department over the above time period. MIC values were determined via the VITEK® 2 Compact automated system (bioMérieux) and interpreted using Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) 2024 guidelines. Susceptibility profiles were expressed as percentages. MICs were expressed in proportions. Geometric means of MIC values were calculated monthly to analyse trends over time.

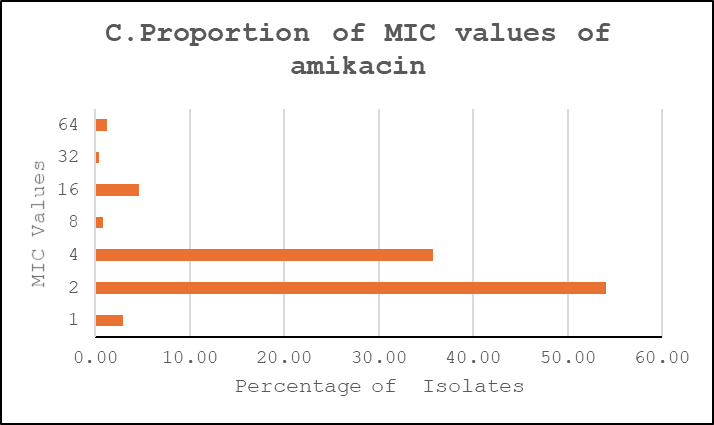

Results: Among 235 urinary E. coli isolates (85% OPD), resistance rates were high for ciprofloxacin (61.4%) and cefuroxime (66.4%), while amikacin remained largely active (92.7% susceptible). MIC distributions showed ciprofloxacin clustered at 4 µg/mL (≈59%), cefuroxime dominated by very high MICs (≈67% ≥64 µg/mL), and amikacin concentrated at low MICs (≈54% at 2 µg/mL).

Conclusion: High resistance to ciprofloxacin and cefuroxime was observed among urinary E. coli isolates, while amikacin remained highly active. These findings underscore the need for guideline-based empirical therapy guided by local antibiograms and strengthened antimicrobial stewardship. However, as results are based solely on laboratory data without clinical correlation, the observed resistance patterns should be interpreted with caution.

KEYWORDS: Aminoglycoside; Antimicrobial Resistance; Cephalosporin; Fluoroquinolone; Susceptibility Patterns

INTRODUCTION

Antimicrobials have transformed medicine, making previously fatal infections treatable and enabling procedures like chemotherapy and organ transplantation. Timely antimicrobial administration, especially in sepsis, reduces morbidity and saves lives1.

However, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has emerged as a major challenge in clinical practice, increasing both treatment complexity and financial burden on patients. In Intensive Care Units (ICU), rising Gram-negative resistance has led to heightened morbidity and mortality2. According to the landmark GRAM study, AMR caused over 1.2 million deaths globally in 20193. AMR is now considered a major threat to global health, food security, and development, largely driven by genetic mutations following prolonged antimicrobial exposure4.

India has seen a 65% rise in antimicrobial consumption, contributing to the development of resistant strains or “superbugs,” which complicate the treatment of common infections4. Understanding the impact of AMR and identifying key pathogen–drug resistance combinations is crucial for informed, local policy-making5.

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) is the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial that prevents visible bacterial growth. It is the gold standard for determining bacterial susceptibility in clinical microbiology6,7. E. Coli is a major Gram-negative pathogen in both hospital and community settings, particularly in urinary tract infections8. Resistance in E. Coli has risen sharply, with fluoroquinolone overuse—especially ciprofloxacin—leading to high resistance rates8. Many strains also produce β-lactamases that inactivate second-generation cephalosporins like cefuroxime9. Conversely, aminoglycosides such as amikacin remain effective against many resistant E. Coli strains9,10.

Because resistance patterns vary by region, local MIC surveillance is essential. Institutional antibiograms guide empirical therapy and support antimicrobial stewardship. Hence, this study at our tertiary care centre in Hyderabad analyzed MIC trends and susceptibility patterns of E. Coli isolates of urine to ciprofloxacin, cefuroxime, and amikacin.

METHODOLOGY

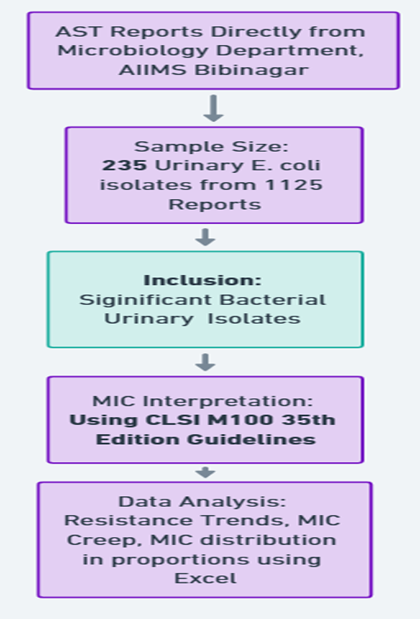

This retrospective observational study was conducted at a Tertiary care centre in Hyderabad from August to November 2024 after getting approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee. Antimicrobial susceptibility test reports with MICs of E. Coli isolates data was collected directly from microbiology laboratory records. Data was extracted from laboratory archives based on inclusion criteria of significant bacterial urinary isolates. (Figure1). Significant bacteriuria is defined as presence of ≥105 (100,000) colony-forming units (CFU) of bacteria per milliliter of urine in a properly collected midstream clean-catch urine sample or for catheterized/supra pubic samples, patient is on antibiotic lower threshold even 103 CFU/ml considered significant. Proper sample collection, transport, processing, and peporting was carried out as per the departmental SOP.

Figure 1: Study methodology flowchart

MIC values were determined using the VITEK® 2 Compact automated system (bioMérieux), which utilizes a standardized broth microdilution method, and all results were interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M100, 34th edition. The interpretive MIC breakpoints applied for Escherichia coli (Enterobacterales) in this study were as follows:14

-

Ciprofloxacin — Susceptible (S) ≤ 0.25 µg/ml; Intermediate (I) = 0.5 µg/ml; Resistant (R) ≥ 1 µg/ml.

-

Cefuroxime — Susceptible (S) ≤ 4 µg/ml; Intermediate (I) = 8–16 µg/ml; Resistant (R) ≥ 32 µg/mL.

-

Amikacin — Susceptible (S) ≤ 4 µg/ml; Intermediate (I) = 8 µg/ml; Resistant (R) ≥ 16 µg/ml.

These CLSI breakpoints were applied to the MIC dilutions reported by the VITEK® 2 Compact (bioMérieux) AST-GN cards to assign categorical interpretations (S/I/R). Any off-scale VITEK MICs were recorded in the highest/lowest reported bin and included in MIC50/MIC90 and frequency-distribution summaries. Quality control procedures were applied in each run by testing standard reference strains as recommended by CLSI to ensure accuracy and consistency of the results. Descriptive statistical analysis was performed. Ranges of MIC values are represented in the table, and percentages were used to summarise the distribution of various clinical settings and susceptibility patterns. MICs were expressed in proportions to characterise the MIC distributions given their relatively consistent pattern. Proportional analyses were used to compare the relative frequencies of urinary isolates in clinical settings.

RESULTS

A total of 1,125 clinical isolates were evaluated, of which 324 were confirmed as E. Coli. Among these isolates, 235 (72.8%) were from urine samples. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) data for these urinary E. Coli isolates—including ciprofloxacin, cefuroxime, and amikacin was analyzed. The majority of patients belonged to the 30–60 years age group, and predominately females. Details are shown in (Table -1).

Table 1: Demographic profile, clinical samples, and setting distribution of E. coli isolates data collected from tertiary care centre

|

SI no |

Section |

Parameter |

Category |

n (%) |

|

1. |

I.Demographics (Urinary isolates only, |

Age Group (Years) |

<18 |

19 (8.1%) |

|

18–30 |

50 (21.3%) |

|||

|

30–60 |

108 (45.9%) |

|||

|

>60 |

58 (24.7%) |

|||

|

Sex |

Female |

145 (61.7%) |

||

|

Male |

90 (38.3%) |

|||

|

2.. |

III. Clinical Setting (n = 235) |

Setting |

OPD |

211 (89.7%) |

|

IPD |

20(8.5%) |

|||

|

ICU |

4(1.7%) |

Antimicrobial susceptibility patterns

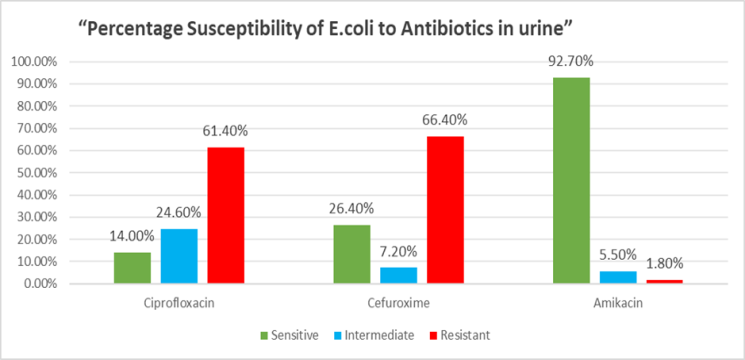

Figure 2 shows antimicrobial susceptibility testing results. Ciprofloxacin showed 14% susceptibility and 61.40% resistance 24.60% intermediate. The majority of urinary isolates were resistant to ciprofloxacin and cefuroxime, whereas amikacin remained effective against nearly all strains.

Figure 2: Percentage of susceptibility of E. Coli to Ciprofloxacin, cefuroxime and amikacin in urine samples

Proportions of MIC Values

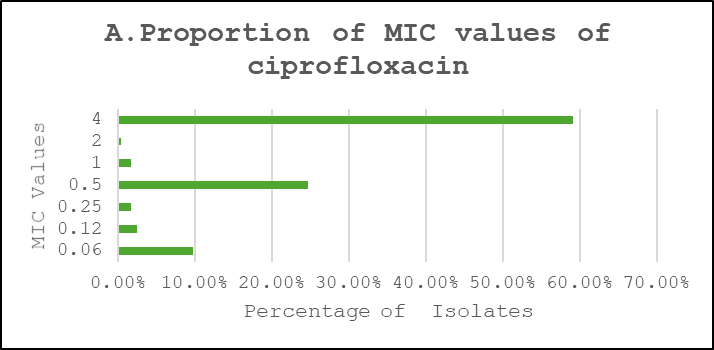

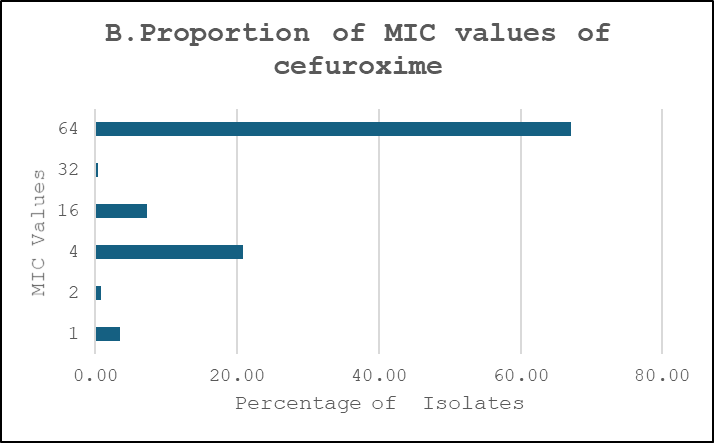

Ciprofloxacin showed a broader distribution concentrated around intermediate-to-high dilutions, cefuroxime exhibited a predominance of very high MICs consistent with high-level resistance, and amikacin retained lower MICs for the majority of isolates (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Proportions of MIC Values. A. Ciprofloxacin, B. Cefuroxime, C. Amikacin

DISCUSSION

In this four-month surveillance (August–November 2024) of 235 urine culture positive reports of Escherichia coli, high resistance was observed to ciprofloxacin (61.4%) and cefuroxime (66.4%), whereas amikacin retained excellent activity, with 97.8% of isolates susceptible. Urinary isolates dominated, reflecting the known role of E. Coli as the leading uropathogen in UTIs11 .These findings align with global trends, where Escherichia Coli accounts for ~75% of uncomplicated UTIs11, and resistance to ciprofloxacin reaches 49% in Colombia12 and 68% in Zambia13

A systematic review from the Asia-Pacific region included 24 studies from 11 of 41 countries. Reported resistance to commonly used antibiotics such as trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, and ceftriaxone ranged widely—from 33% to 90%—with the highest prevalence observed in Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia. 14

MIC distribution for ciprofloxacin showed that 54% of isolates had an MIC of 2 µg/ml, and 36% had 4 µg/ml—borderline or above the resistance threshold—indicating a shift toward resistance. Only 7% showed very high MICs (≥8 µg/ml), suggesting an evolving but not yet fully resistant population. Reported Ciprofloxacin resistance ranged between 6.3% and 79.6% in laboratory-based studies and between 12.9% and 90.1% in population-based studies. Another prospective study reported that the sensitivity to ciprofloxacin was 27%.15

Fluoroquinolone resistance may reflect historical overuse and clonal expansion of resistant strains, persisting despite reduced prescriptions16. Cefuroxime showed the highest resistance among the three drugs studied. MIC distribution revealed that 66% of isolates had mics ≥64 µg/ml, well beyond the susceptibility breakpoint, implying widespread ESBL production. Phenotypic data confirmed that 42.8% of E. Coli isolates were ESBL-positive. Amikacin remained largely effective, with negligible resistance, consistent with international data13. Its continued efficacy suggests limited prevalence of aminoglycoside-modifying enzymes or 16S RNA methyltransferases, though clinical use may be restricted due to nephrotoxicity.

In line with current national and international guidance, empirical therapy for uncomplicated lower urinary tract infection should be guided by local antibiograms and—where local susceptibility allows—prioritise agents such as nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin or trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole rather than fluoroquinolones or second-generation cephalosporins; fluoroquinolones and 2nd-generation cephalosporins should not be used routinely as first-line empirical therapy and should be reserved only when local data support their use 17-19. For severe or complicated infections (for example, urosepsis or suspected infection with multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales), a parenteral aminoglycoside such as amikacin may be considered if in-vitro susceptibility is confirmed; however, its use should be restricted to such indications, adjusted for renal function, and accompanied by therapeutic-drug monitoring and clinical surveillance because of the risk of nephrotoxicity and ototoxicity20,21. These recommendations reinforce the need for continuous, institution-level surveillance and antimicrobial stewardship so that empirical prescribing reflects current local susceptibility patterns.

Limitations of the study

These MICs/resistance findings must be interpreted with caution, as most available data are derived solely from laboratory-based culture and sensitivity reports, without adequate correlation to clinical details. Important factors such as confirmation of true urinary tract infection prior to sample collection, the extent of contamination during collection, transport, or laboratory processing, and the patient’s antimicrobial exposure history within the preceding 90 days were not consistently reported. Similarly, data regarding the presence of urinary catheters or foreign bodies (which may reflect colonization rather than infection) and immune status of the patients were often unavailable. Without accounting for these parameters, the true resistance profile of urinary pathogens cannot be accurately established.

CONCLUSION

This retrospective analysis of urinary Escherichia coli isolates collected at our tertiary care centre between August and November 2024 demonstrates concerning resistance patterns. High rates of resistance were observed to cefuroxime (66.3%) and ciprofloxacin (59.1%), substantially limiting their value as empirical choices for urinary E. coli infections in our setting. By contrast, amikacin retained excellent in-vitro activity, with 97.8% of isolates susceptibility. MIC distributions paralleled these findings: ciprofloxacin and cefuroxime MICs were shifted toward higher dilutions while amikacin MICs remained low. These results emphasise the need for ongoing, local antimicrobial surveillance and for empiric prescribing to be guided by up-to-date susceptibility data. However, the findings should be interpreted with caution, as they are based solely on laboratory culture results without correlation to patient-level clinical factors. Future studies integrating clinical and microbiological data are essential to provide a more accurate reflection of true resistance profiles and to inform rational antibiotic use

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

KRH: Conceptualisation; Data curation; Writing the draft, Methodology; Conceived and Designed the Analysis.

ME: Conceptualization; Investigation; Methodology; Supervision; writing the draft

RS: Validation; Resources, Data curation

NK: Review of manuscript

JCK: Review of manuscript

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Nil

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

None

DECLARATION FOR THE USE OF GENERATIVE ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI) IN SCIENTIFIC WRITING:No part of the manuscript was generated unethically using AI.

REFERENCES

-

Ibrahim H, Soliman S. Clinician’s knowledge and performance regarding antibiotics stewardship. Mansoura Nurs J. 2024;11(2):55–63.

-

Savanur SS, Gururaj H. Study of antibiotic sensitivity and resistance pattern of bacterial isolates in intensive care unit setup of a tertiary care hospital. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2019;23(12):547–55.

-

Kıratlı K, Aysin M, Ali MA, Ali AM, Zeybek H, Köse Ş. Evaluation of doctors’ knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, awareness and practices on rational antimicrobial stewardship in a training and research hospital in Mogadishu, Somalia. Infect Drug Resist. 2024;17:2759–71.

-

Patil JP, Baig MS, Kulkarni VA. Knowledge, attitude, and perception of prescribers about antimicrobial stewardship in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Res Med Sci. 2023;11(9):3357–64.

-

Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet. 2022;399(10325):629–55.

-

Mondal S, Mandal A, Saha S, Chakrabarty PS, Das D. Minimum inhibitory concentration creep in Enterobacterales – a rising concern. Asian J Med Sci. 2024;15(6):81–5.

-

Mandal J, Acharya NS, Buddhapriya D, Parija SC. Antibiotic resistance pattern among common bacterial uropathogens with a special reference to ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli. Indian J Med Res. 2012;136(5):842–9.

-

Niranjan V, Malini A. Antimicrobial resistance pattern in Escherichia coli causing urinary tract infection among inpatients. Indian J Med Res. 2014;139(6):945–8.

-

Cho SY, Choi SM, Park SH, et al. Amikacin therapy for urinary tract infections caused by extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli. Korean J Intern Med. 2016;31(1):156–61.

-

Zhou Y, Zhou Z, Zheng L, et al. Urinary tract infections caused by uropathogenic Escherichia coli: mechanisms of infection and treatment options. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(13):10537.

-

Villalobos EST, de la Ossa JAMD, Meza YP, Gulloso ACR. Nine-year trend in Escherichia coli resistance to ciprofloxacin: cross-sectional study in a hospital in Colombia. Cad Saude Publica. 2024;40(7):e00031723.

-

Kasanga M, Shempela DM, Daka V, et al. Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Escherichia coli isolated from clinical and environmental samples: findings and implications. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2024;6(2):dlae061.

-

Tchesnokova V, Larson L, Basova I, et al. Increase in the community circulation of ciprofloxacin-resistant Escherichia coli despite reduction in antibiotic prescriptions. Commun Med (Lond). 2023;3(1):110.

-

Sardar A, Basireddy SR, Navaz A, Singh M, Kabra V. Comparative evaluation of fosfomycin activity with other antimicrobial agents against E. coli isolates from urinary tract infections. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(2):DC26–DC29. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2017/23644.9440.

-

Sugianli AK, Ginting F, Parwati I, de Jong MD, van Leth F, Schultsz C. Antimicrobial resistance among uropathogens in the Asia-Pacific region: a systematic review. JAC Antimicrob Resist. 2021;3(1):dlab003. doi:10.1093/jacamr/dlab003.

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. 34th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Wayne (PA): CLSI; 2024.

-

Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, Wullt B, Colgan R, Miller LG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(5):e103–e120. doi:10.1093/cid/ciq257.

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). Urinary tract infection (lower): antimicrobial prescribing (NG109). London: NICE; 2018 [reviewed 2019]. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng109.

-

Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR). Treatment Guidelines for Antimicrobial Use in Common Syndromes. New Delhi: ICMR; 2019. Available from: https://www.icmr.gov.in/.

-

Jaiswal S, Agarwal A, Singh SP, Mohan P. Therapeutic drug monitoring of amikacin in hospitalized patients: a pilot study. Med J Armed Forces India. 2022;79(Suppl 1):S119–S124. doi:10.1016/j.mjafi.2022.02.006.

-

Jenkins A, Thomson AH, Brown NM, Semple Y, Sluman C, MacGowan A, et al. Amikacin use and therapeutic drug monitoring in adults: do dose regimens and drug exposures affect either outcome or adverse events? A systematic review. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71(10):2754–9. doi:10.1093/jac/dkw250.

Submit a Manuscript:

Copyright © Author(s) 2025. JASPI- Journal of Antimicrobial Stewardship Practices and Infectious Diseases.