Neurocysticercosis versus CNS Tuberculosis: A Diagnostic Dilemma in an Endemic Setting

JASPI September 2025 / Volume 3 /Issue 3

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Angural Y, Bairwa M, Kant R, et al.Neurocysticercosis versus CNS Tuberculosis: A Diagnostic Dilemma in an Endemic Setting. JASPI. 2025;3(3):32-36 DOI: 10.62541/jaspi096

ABSTRACT

KEYWORDS: Central Nervous System Tuberculosis; CBNAAT (Cartridge-Based Nucleic Acid Amplification Test); Ring-enhancing brain lesions; Neurocysticercosis; Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

INTRODUCTION

Multiple ring-enhancing lesions are commonly observed radiological abnormalities. They can be infectious, inflammatory, neoplastic, vascular.1 Out of infectious causes, neurocysticercosis (NCC) and central nervous system tuberculosis (CNS TB) are important causes as they are notable public health concerns in developing countries.2 NCC and CNS TB share overlapping clinical features, including headache, fever and altered mental status, which can lead to diagnostic uncertainty, particularly when relying solely on radiological findings.

The coexistence of these infectious conditions in a single individual is not well documented in the literature with relatively few data on incidence and prevalence, suggesting it is relatively uncommon. NCC, caused by larvae of Taenia solium, is one of the major causes of adult-onset seizures and focal neurological deficits in endemic areas.2 Whereas CNS TB, often presents with severe complications like meningitis, hydrocephalus and tuberculomas. Distinguishing between NCC and tuberculomas remains challenging due to similar radiological patterns, including multiple ring-enhancing lesions and perilesional edema. Misdiagnosis can lead to inappropriate therapy and clinical deterioration, including wrong antimicrobials and rise in antimicrobial resistance.

This case illustrates a diagnostic dilemma in which the initial radiological impression of NCC led to antiparasitic therapy, but subsequent clinical deterioration and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis revealed the diagnosis of CNS TB. It emphasises the importance of comprehensive evaluation, including cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification tests (CBNAAT), in accurately diagnosing CNS infections in endemic regions.

CASE PRESENTATION

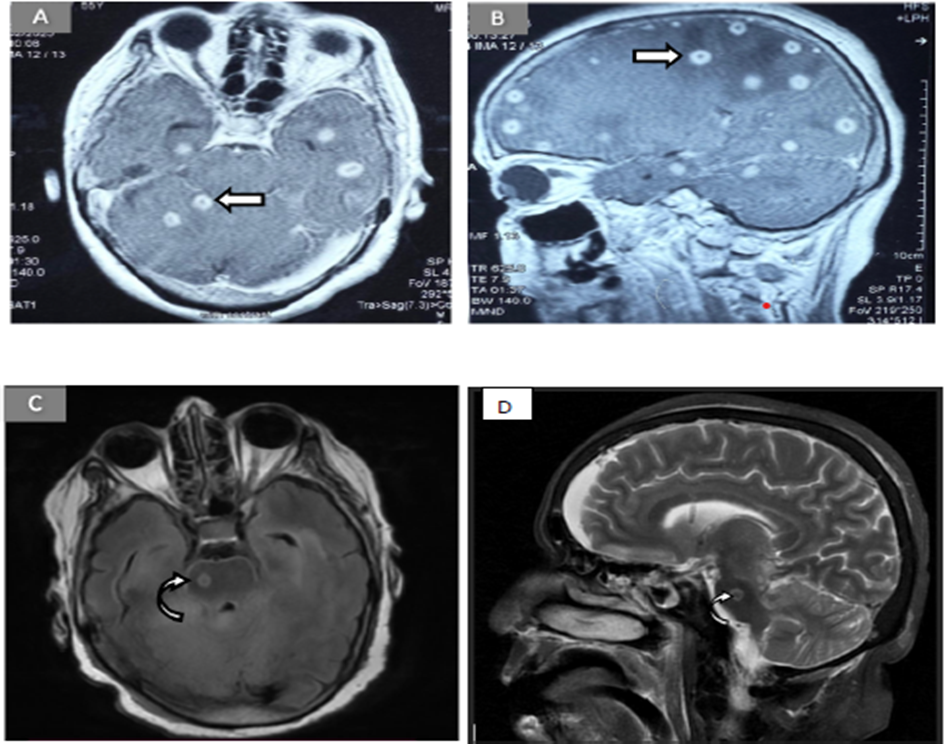

A 55-year-old lady from India, without prior comorbidities, presented during the summer with two months of intermittent low-grade fever and holocranial headache without focal neurological symptoms. A contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (CEMRI) brain showed multiple ring-enhancing lesions in bilateral cerebral, cerebellar hemispheres and pons with perilesional oedema and eccentric scolex, suggestive of NCC [Figure 1 (A-B)]. CSF revealed elevated cell counts (predominantly polymorphic), normal glucose, and elevated protein. No further investigations were done to rule out other causes, including TB and she was diagnosed with NCC, primarily on radiological evidence. She was then treated with albendazole for 21 days and corticosteroids, with partial symptom relief. Two months later, she presented with recurrent fever, headache, altered mental status, and a generalized tonic-clonic seizure, necessitating intubation. Examination revealed GCS of E1VtM5, sluggishly reactive pupils, neck rigidity, flaccid tone, and absent deep tendon reflexes in all 4 limbs. The lack of complete response to albendazole with clinical deterioration prompted reconsideration of the diagnosis.

Upon admission, initial laboratory investigations revealed anaemia of chronic disease, thrombocytopenia and neutrophilic leucocytosis (Table 1). Liver and renal biochemistry were within normal limits. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein were elevated. Repeat non-contrast computed tomography (NCCT) scan of head revealed hydrocephalus, for which external ventricular drain (EVD) insertion was done. CEMRI brain revealed multiple ring-enhancing lesions involving the brainstem with leptomeningeal enhancement. Multiple vasculitic infarcts were seen in both cerebral hemispheres and brainstem, with few basal exudates involving bilateral optic nerves [Figure 1(C-D)].

Figure 1: MRI brain imaging reveals multiple well-defined, rounded lesions in both axial and sagittal T2-weighted sections (Figures A and B). These lesions exhibit a characteristic pattern of peripheral hyper intensity with an eccentric hypointense nodule, often referred to as the “eccentric target sign” (arrow). Figure C- T2-weighted axial image, shows a solitary lesion in the brainstem region, appearing hyperintense peripherally with a hypointense center (curved arrow). Figure D, a T2-weighted sagittal image, reveals the corresponding lesion in the brainstem as hypointense with notable peripheral hyperintensity (curved arrow), consistent with the cystic or necrotic nature of the lesion.

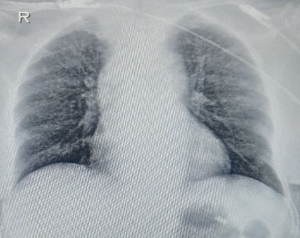

On magnetic resonance spectroscopy, lipid lactate peak was present. ELISA for IgG antibodies against cysticercosis was negative. Skiagrams of limbs and stool analysis showed no evidence of cysticercosis. Tuberculin skin test was positive. CSF analysis showed clear fluid with elevated monomorphic cells, hypoglycorrhachia and elevated protein. Adenosine deaminase (ADA) level was mildly raised. CBNAAT was positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis without rifampicin resistance. Diagnosis of CNS TB was made on a microbiological basis with supportive radiological evidence, and first-line antitubercular therapy (ATT) with corticosteroids was started as per national guidelines. Chest xray was suggestive of miliary pattern (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The chest X-ray (poster anterior view) reveals a diffuse, bilateral, fine nodular pattern throughout both lung fields.

Endotracheal aspirate CBNAAT was also positive for Mycobacterium tuberculosis without rifampicin resistance. Contrast-enhanced CT thorax and abdomen revealed tree-in-bud pattern with mediastinal and hilar lymphadenopathy suggestive of tuberculosis. Disseminated tuberculosis in the form of miliary TB, hydrocephalus, vasculitic infarcts and tuberculous meningitis was diagnosed based on microbiological and radiological evidence, and ATT was continued on the background of NCC (recovered granuloma).

Table 1: Basic and advanced investigations of the patient.

Investigation | SI unit | Reference Range | 1st presentation (outside) | 2nd presentation in our hospital (Day 4) | Day 25 |

Hb | g/dl | 13-17 | – | 11.9 | 10.3 |

MCV | (fL) | 78-98 | – | 86.4 | 88.8 |

TLC (x1000) | ×103 cells/mm3 | 4-11 | – | 16680 | 5780 |

DLC (N/L/M/E) | % | 40-70/20- 40/2-8/1-6 | – | 94.5/2.2/3/0.3 | 78.3/14.6/6.3/0.7 |

Platelet | ×1000 cells/mm3 | 150-400 | – | 73 | 155 |

Total Bilirubin | mg/dl | 0.3 – 1.2 | – | 0.75 | – |

Direct Bilirubin | mg/dl | 0 – 0.2 | – | 0.13 | – |

SGPT | U/L | 0-50 | – | 31 | – |

SGOT | U/L | 0-50 | – | 56 | – |

ALP | U/L | 30-120 | – | 74 | – |

GGT | U/L | 0-55 U/L | – | 116 | – |

Total protein | g/dl | 6.6-8.3 gm/gl | – | 5.6 | – |

Albumin | g/dl | 3.5-5.2 g/dl | – | 2.7 | – |

Globulin | g/dl | 2.5-3.2g/dl | – | 2.9 | – |

Urea | mg/dl | 17-43 | – | 121 | – |

Creatinine | mg/dl | 0.72-1.18 | – | 0.77 | – |

ESR | mm/hr | 0-20 | – | 43 | 20 |

CRP | mg/L | 0-1 | – | 114 | 32 |

CSF cell count | /mm3 | 0-5 | 840 cells, 91% polymorphs | 240 cells, 70% monomorphs | Acellular |

CSF sugar/ corresponding blood sugar | mg/dl | 40-80 | 145/ 163 | 65/188 | 73/ 145 |

CSF protein | mg/dl | 15-45 | 262 | 192 | 80 |

CSF ADA | U/L | 0-10 | 12.2 | 25 | 3.5 |

CSF microbiology | Culture-sterile | Culture- sterile, India ink and KOH staining- negative | Culture- sterile, India ink and KOH staining- negative | ||

CSF CBNAAT | – | POSITIVE | – |

Abbreviations: Hb – haemoglobin, MCV – mean corpuscular volume, TLC – total leukocyte count, DLC – differential leukocyte count, ALT – alanine transaminases, AST – aspartate transaminases, ALP – alkaline phosphatase, GGT – gamma-glutamyl transferase, ESR –erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP– C-reactive protein

DISCUSSION

A middle-old aged woman from a TB-endemic region initially diagnosed with neurocysticercosis (based on MRI) was treated with albendazole and corticosteroids. Clinical deterioration prompted repeat imaging, revealing hydrocephalus, leptomeningeal enhancement, basal exudates, and vasculitic infarcts suggestive of CNS tuberculosis. CSF analysis and CBNAAT confirmed Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, establishing CNS TB as the final diagnosis. NCC and CNS TB are common neurological infections in developing countries like India, and both can present with seizures, headache, and altered mental status, making clinical distinction challenging. Furthermore, both the diseases are frequently associated with ring-enhancing lesions on neuroimaging, thus posing a diagnostic dilemma in an endemic setting like ours.3

CNS TB accounts for 1% of all tuberculosis cases and has high mortality and morbidity. Patients often present with fever, headache, neck stiffness, altered sensorium, and focal deficits. About 1% present with tuberculomas, appearing as solitary or multiple ring-enhancing lesions, with possible seizures and signs of raised intracranial pressure like papilledema. CSF typically shows lymphocytic pleocytosis, elevated protein, and hypoglycorrhachia, but this is non-diagnostic. ADA levels can be raised but are also non- specific. Mantoux test is supportive but not diagnostic. CBNAAT allows rapid diagnosis and detection of rifampicin resistance, with Xpert/MTB RIF assay having 95% specificity.4,5 Microbiological testing by culture for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which however time consuming, remains the gold standard for diagnosis. It can additionally detect drug resistance. In this regard, yield of a liquid culture system (BACTEC Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube system) is much higher than a solid culture (Lowenstein-Jensen).6

Radiological differentiation – In tuberculous meningitis, the MRI triad includes basal meningeal enhancement with exudates, infarctions, and hydrocephalus. Tuberculomas appear hypointense on T2 with irregular ring enhancement; liquefied areas are hyperintense, and chronic lesions may show central calcification (target sign). Vesicular NCC shows ring-enhancing lesions with a central scolex without oedema, while colloidal and granular stages have thick-walled enhancing lesions with oedema, the latter having a thicker wall.7 Proton MRS shows high lipid peak and increased choline/creatine ratio in CNS TB, while elevated lactate, alanine, succinate, choline with reduced N-acetyl aspartate and creatine favour NCC.8,9

A comprehensive diagnostic approach beyond imaging is needed, especially when response is inadequate or atypical features emerge. Integration of molecular diagnostics like CBNAAT into first-line evaluation may reduce diagnostic delays and improve outcomes. Mis-or-partial diagnosis can lead to harmful consequences as treatment for both differs, and wrong treatment can flare the primary disease. Risks include immunosuppression from steroids exacerbating TB, or inappropriate ATT worsening NCC, while delayed TB treatment risks progression and poor outcomes. Hence, close follow-up is essential after empirical treatment of one such that diagnostic errors if they occur can be detected and corrected at the earliest.3,10

This case illustrates how diagnosing NCC and starting steroids without excluding TB can worsen undiagnosed TB. Empirical therapy without microbiological confirmation risks treatment failure, resistance, and AMR. Radiology alone cannot reliably distinguish NCC from CNS TB, as both can present with ring-enhancing lesions and similar clinical features. In high- burden settings, CNS TB should be suspected when there is no improvement on antiparasitic therapy or when complications like hydrocephalus occur. It should always be the first differential to be ruled out before putting patients on steroids.

CONCLUSIONS

In endemic areas, clinicians must exercise caution when diagnosing ring-enhancing CNS lesions. NCC and CNS TB are common neurological infections with overlapping clinical and radiological features, leading to diagnostic dilemma. Chest radiograph and Mantoux test should be mandatory before starting steroids in NCC. Systemic symptoms like fever should be evaluated for TB in a radiologically clear case of NCC where meningitis is suggested by CSF.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None

DECLARATION FOR THE USE OF GENERATIVE ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE (AI) IN SCIENTIFIC WRITING:

No

INFORMED CONSENT

Patient consent was duly obtained.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

SOURCE OF FUNDING

No funding was received for this research paper.

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

KC and YA : writing the draft, data collection

RK: supervision, approval

MB : conceptualization, review and editing, approve

REFERENCES

Garg RK, Sinha MK. Multiple ring-enhancing lesions of the brain. J Postgrad Med. 2011;57(4):307-16. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.70939

García HH, Nash TE, Del Brutto OH. Clinical symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment of neurocysticercosis. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(12):1202-15. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70094-8.

Bajracharya N, Lamichhane S, Lamichhane P, Bishowkarma D, Acharya A, Sharma S, Pandit P. Diagnostic Dilemma of Central Nervous System Tuberculosis with Neurocysticercosis and Neurosarcoidosis: A Case Report. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2023 Feb 1;61(258):188-191.

Rock RB, Olin M, Baker CA, Molitor TW, Peterson PK. Central nervous system tuberculosis: pathogenesis and clinical aspects. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2008;21(2):243. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00042-07

Boulware DR. Utility of the Xpert MTB/RIF Assay for Diagnosis of Tuberculous Meningitis. PLoS Med. 2013;10(10):e1001537. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001537.

Garg RK. Microbiological diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis: Phenotype to genotype. Indian J Med Res. 2019 Nov;150(5):448-57. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_1145_19.

Singh SK, Hasbun R. Neuroradiology of infectious diseases. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2021 Jun 1;34 (3):228-37. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000725.

Pretell EJ, Martinot C Jr, Garcia HH, Alvarado M, Bustos JA, Martinot C; Cysticercosis Working Group in Peru. Differential diagnosis between cerebral tuberculosis and neurocysticercosis by magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2005 Jan-Feb;29(1):112-4.

Pandit S; Lin A; Gahbauer H; et al. MR Spectroscopy in Neurocysticercosis. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001 Nov;25(6):950-2. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200111000-00019.

Chaoshuang L, Zhixin Z, Xiaohong W, Zhanlian H, Zhiliang G. Clinical analysis of 52 cases of neurocysticercosis. Tropical Doctor. 2008;38(3):192-4. doi: 10.1258/td.2007.070285.

Submit a Manuscript:

Copyright © Author(s) 2025. JASPI- Journal of Antimicrobial Stewardship Practices and Infectious Diseases.