This is a platform for sharing bedside or laboratory stories (text, image, video) on integrated antimicrobial stewardship activities in daily practices by both the general public and healthcare workers. These contributions aim to create better practice opportunities for everyone in infection prevention, accurate diagnosis, and responsible antimicrobial prescriptions—fostering a better world through a One-Health approach.

We invite anyone to share their own story, which will be published in each issue of JASPI following the editor’s review.

Kindly submit your stories using [Click Here].

Regards,

Editor-in-Chief

JASPI/Pearls/001/2024 |

Polymicrobial Infection in COPD exacerbation

Drupad Das, *Prasan Kumar Panda

Department of Medicine (ID Division), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, India

*Corresponding author: Dr. Prasan Kumar Panda, Department of Medicine (ID Division), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, 249203, Uttarakhand, India

Email: motherprasanna@rediffmail.com

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Vignette

A middle-aged, thinly built woman who smokes beedi and has a history of biomass exposure, has been suffering from COPD for the last 4 years. She has been taking inhaled betamethasone and tiotropium. Additionally, she had uncontrolled diabetes for a few months. She presented with fever, productive cough, shortness of breath, and chest pain for 5 days. Chest X-ray and CT confirmed pneumonia, cavities, and abscesses in both lungs. Repeated sputum and bronchoalveolar lavage confirmed Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Aspergillus fumigatus. Along with supportive therapy, she was treated with tablet levofloxacin and injection amikacin for 6 weeks based on culture sensitivity reports, and capsule itraconazole for 6 months. She recovered completely to her baseline COPD and diabetes status.

|

Ques. What is this polymicrobial diagnosis (figure) in this patient?

A) Polymicrobial – Synergy

B) Polymicrobial- Antagonism

C) Polymicrobial- Mutualism

D) Polymicrobial- Commensalism |

Answer: Kindly check answer in the supplementary issue (link/doi of that issue CLICK HERE!)

JASPI/Pearls/002/2024 |

Diagnostic Dilemma in Fever with Right Chest Pain

Shiv Narayan Sahu, Rajshekhar Lohar*

Department of Internal Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, India

*Corresponding author: Dr. Rajshekhar Lohar, Department of Internal Medicine (ID Division), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh- 249203, Uttarakhand, India

Email: dr.rajshekharlohar3@gmail.com Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Vignette

A young man in his late twenties, labourer, presented with a 20-day history of low-grade intermittent fever, accompanied by right lower chest pain radiating to the right shoulder and anorexia. The pain worsened with deep inspiration and coughing. Over the past 7 days, he had developed a productive cough with yellowish expectoration. He denied any recent travel or known exposure to tuberculosis but reports occasional alcohol consumption. Physical examination revealed tenderness over the right upper quadrant and reduced breath sounds at the right lung base. Initial laboratory tests showed leucocytosis. A chest X-ray (figure 1) revealed a right-sided pleural effusion.

Figure 1: Chest Xray PA view |

Ques. What is the next best investigation?

A) Pleural fluid aspiration B) Sputum examination

C) USG of chest and abdomen

D) CECT chest and abdomen |

JASPI/Pearls/003/2024 |

All Hemorrhagic Pleural Effusions are Not Infective

Amit Kumar Mathur*

Department of Internal Medicine (ID Division), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, India

*Corresponding author: Amit Kumar Mathur, Department of Internal Medicine (ID Division), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh-249203, Uttarakhand, India

Email: ak668659@gmail.com

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Vignette

A middle aged male, who has been suffering from Chronic kidney Diseases-5D, Chronic heart failure and hypertension non-compliant to medications and renal replacement therapy (RRT), presented with decreased urine output, anorexia, shortness of breath, bilateral pedal oedema, abdominal distention, productive cough and vomiting over the past 8-10 days. There was no history of chest trauma, significant weight loss, fever, or night sweats. Routine investigations revealed severe uraemia (Urea – 290 mg/dl) and a normal INR [1.07]. Chest X-ray suggested left pleural effusion and abdominal ultrasound revealed ascites, both atypical fluid collections were grossly haemorrhagic upon tapping. Empirically, the patient was treated with ceftriaxone and azithromycin for a suspected infective aetiology; however, there was no significant clinical improvement. Further evaluation, including a contrast-enhanced CT thorax, suggested malignancy as a cause of the hemorrhagic effusion. The patient received alternate day RRT and demonstrated clinical and vital improvements. Follow-up imaging, including X-ray and point-of-care ultrasound, revealed complete resolution of the pleural effusion and ascites.

|

Ques. Which of the following best reflects a key principle of stewardship in this case? A. Antibiotic therapy should be started empirically in patients with suspected infection, and stopped only after cultures confirm the absence of infection

B. Empirical use of antibiotics was appropriate due to the presence of respiratory symptoms and radiological findings, even without microbial confirmation

C. Before initiating antibiotic therapy, a thorough diagnostic workup, including pleural fluid analysis and uremic workup, should have been prioritized to avoid unnecessary antimicrobial use

D. Given the patient’s non-compliance and systemic symptoms, broad-spectrum antibiotics were necessary to cover potential multidrug-resistant organisms |

Chest X-ray -> Gross left-sided pleural effusion. | |

| |

Hemorrhagic pleural effusion |

Answer: Kindly check answer in the supplementary issue (link/doi of that issue CLICK HERE!)

JASPI/Pearls/004/2024 |

Can Skin Findings Suggest Disseminated Opportunistic Infection, Malignancy in HIV/ AIDS?

Krishna Chakravarty*, Rajshekhar Lohar

Department of Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, India

*Corresponding author: Krishna Chakravarty, Department of Internal Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh-249203, Uttarakhand, India

Email: chakravartykrishna99@gmail.com

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Vignette

A person living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLHIV) in his early thirties, an antiretroviral therapy (ART) defaulter, presented with a gradual onset holocranial, pulsatile headache for 10 days, which worsened on forward bending. The headache was followed by a few episodes of projectile vomiting. He also gave the history of anorexia, weight loss, and low-grade fever.

On examination, he was oriented and obeyed commands. He had pallor and multiple raised, skin-colored, umbilicated lesions over his face, scalp, and forearm, some with central ulceration (Images 1a and 1b). He was febrile, and neck stiffness was present. Examination of other systems was non-contributory.

| Ques.What is your clinical diagnosis? A. Kaposi’s Sarcoma

B. Molluscum contagiosum

C. Histoplasmosis

D. Cryptococcosis

E. MAC infection |

Image-1

Answer: Kindly check answer in the supplementary issue (link/doi of that issue CLICK HERE!)

JASPI/Pearls/005/2024 |

Can CBNAAT Positivity in Fluid Confirm Tuberculosis Disease?

Darshan B, Rajat Sharma*

Department of Internal Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, India

*Corresponding author: Rajat Sharma, Department of Internal Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, India

Email: surajdostpuriya@gmail.com

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Vignette

A young man in his early twenties, a chef from Delhi, presented with a 15-day history of low-grade fever in the evenings, associated with progressive painless bilateral pedal edema. Over the past 7 days, he had developed a gradual painless abdominal distension. In the last 2 days, he developed cough and worsening dyspnoea. He denied any recent travel, past history of tuberculosis, or known exposure to tuberculosis. No history of oral ulcers, sicca symptoms, photosensitivity, alopecia, or Raynaud’s phenomenon.

On examination, he was dyspneic with raised jugular venous pressure (JVP), and Ewart’s sign was noted on chest auscultation along with a pericardial rub on cardiac auscultation. Electrocardiography (ECG) showed electrical alternans, and the chest roentgenogram (Image 1) demonstrated an enlarged cardiac silhouette.

An emergency pericardiocentesis was performed using a pigtail drain. The complete hemogram, kidney function tests, serology, and procalcitonin levels were non-contributory. However, liver enzymes and total bilirubin were modestly elevated. His ESR was mildly elevated, and the Mantoux test was negative. However, pericardial fluid CBNAAT (Cartridge-based nucleic acid amplification test) came positive.

| Ques.Choose the most likely diagnosis: A. Takotsubo pericarditis

B. TB hypersensitivity pericarditis

C. Viral pericarditis

D. Tubercular pericarditis |

Answer: Kindly check answer in the supplementary issue (link/doi of that issue CLICK HERE!)

|

JASPI/Pearls/006/2025 |

Optimizing Vaccination in CKD: A Case-Based Approach

Darshan B, Prasan Kumar Panda*

Department of Medicine (ID Division), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, India

*Corresponding author: Dr. Prasan Kumar Panda, Department of Medicine (ID Division), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, 249203, Uttarakhand, India

Email: motherprasanna@rediffmail.com

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Vigette

Sourabh, a 31-year-old male farmer, presents with a history of Stage 5D Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) secondary to suspected chronic glomerulonephritis (CGN) and diabetic kidney disease (DKD). He is on maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) through a left AV fistula. His medical history includes systemic hypertension (diagnosed 1.5 years ago), poorly controlled diabetes mellitus with HbA1c of 14.1%, diabetic retinopathy (moderate NPDR), and anemia related to CKD and chronic disease. The patient was recently hospitalized for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) precipitated by community-acquired Pneumonia. During the hospital stay, he was treated with appropriate antibiotics, optimized blood sugars, and underwent two sessions of dialysis.

On follow-up, the patient reports significant improvement. He continues to receive twice-weekly dialysis. Considering his medical condition, he is at increased risk of recurrent infection due to impaired immunity from CKD, diabetes, and regular dialysis. His immunization history was reviewed and he received the Tdap vaccine in childhood.

|

Q. Choose the most appropriate vaccination regimen for this patient, according to CDC 2024 guidelines. A. Pneumococcal vaccine, Hepatitis B vaccine, Influenza vaccine, Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis (Tdap) vaccine, MMR, Varicella, COVID-19. B. Pneumococcal vaccine, Hepatitis B vaccine, Influenza vaccine, Hepatitis A, Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis (Tdap) vaccine, MMR, Varicella, COVID-19. C. Pneumococcal vaccine, Influenza vaccine, Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis (Tdap) vaccine, MMR, Varicella, COVID-19. D. Pneumococcal vaccine, Influenza vaccine, Tetanus-diphtheria-pertussis (Tdap) vaccine, MMR, Varicella, COVID-19. Haemophilus Influenza B, Meningococcal vaccine. |

ANSWER: Kindly check answer in the supplementary issue (link/doi of that issue CLICK HERE!)

JASPI/Pearls/007/2025 |

Krishna Chakravarty*, Rajshekhar Lohar

Department of Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, India

*Corresponding author: Dr. Krishna Chakravarty, Department of Medicine (ID Division), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, 249203, Uttarakhand, India

Email: chakravartykrishna99@gmail.com

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Vignette A 47-year-old woman from rural India presented to the emergency department with a 5-day history of high-grade fever, headache, and abdominal pain. The fever was associated with a dull aching pain in the epigastric region. 3 days into her illness, she developed a dry cough and progressive shortness of breath. Over the last 24 hours, she had become confused, disoriented, and unable to recognize her family members.

On examination, the patient appeared ill and was febrile with a temperature of 103°F, pulse rate of 112 beats per minute, and blood pressure reading of 80/66 mmHg. The respiratory rate was 32 breaths per minute, and the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) score was 8. The patient's airway was secured via endotracheal intubation, and she was placed on mechanical ventilation. Vasopressor support was provided for hypotension resistant to bolus fluid therapy. A small lesion with central necrosis surrounded by erythema (image 1) was noted on her left flank. An abdominal examination revealed hepatomegaly, while the rest of the findings were unremarkable. Blood investigations (table 1) showed neutrophilic leucocytosis with thrombocytopenia, mildly deranged liver enzymes, elevated c-reactive protein and troponin levels.

Table 1: Relevant investigations of the patient

Investigations | Reference range | Patient’s value |

Haemoglobin (g/dL) | 12.0 – 15 | 12.0 |

Total Leucocyte Count (×10³/µL) | 4.0 – 11.0 | 15.18 |

Neutrophils (%) | 40 – 75 | 66 |

Platelets (×10³/µL) | 150 – 450 | 25 |

Serum Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.6 – 1.2 | 0.92 |

SGPT (U/L) | 7 – 56 | 92 |

SGOT (U/L) | 8 – 48 | 621 |

Serum ALP (U/L) | 44 – 147 | 166 |

CRP (mg/L) | < 5 | 228.5 |

Troponin I (ng/L) | < 34.2 | 360.13 |

|

Ques. All of the following statements are true except? A. Eschar is absent in many cases, especially in endemic regions. B. Hidden locations like axilla, groin, and perineum require careful examination. C. Eschar does not indicate severity but aids early diagnosis. D. It can mimic other conditions like anthrax, spider bite, or necrotizing fasciitis. E. Serology is crucial in early diagnosis. |

ANSWER: Kindly check answer in the supplementary issue (link/doi of that issue CLICK HERE!)

JASPI/Pearls/008/2025 |

Krishna Chakravarty*, Rajshekhar Lohar

Department of Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, India

*Corresponding author: Dr. Rajshekhar Lohar, Department of Medicine (ID Division), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, 249203, Uttarakhand, India

Email: dr.rajshekharlohar@gmail.com

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Vignette A 55-year-old previously healthy woman was admitted with a 15-day history of fever, 5 days of jaundice, abdominal pain, vomiting, and 4 days of shortness of breath. She developed an altered sensorium for the last day. Her daughter denied dependences, and history of sudden cardiac death in family..

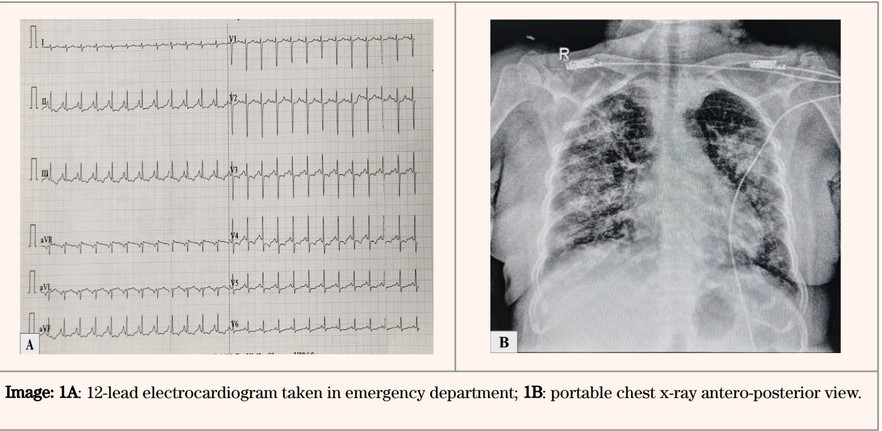

OOn examination, her Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was E3V3M5. She had a temperature of 102°F, a pulse rate of 149 bpm, blood pressure of 80/62 mm of Hg, and respiratory rate of 38/min and required oxygen support to maintain saturation. Bilateral pedal edema was observed, with decreased air entry and fine inspiratory crackles noted in the axillary region upon chest auscultation. Arterial blood gas analysis revealed respiratory acidosis and endotracheal intubation was done for airway protection and respiratory distress. Point-of-care ultrasonography revealed bilateral diffuse bilateral B lines and a non-collapsing inferior vena cava. The chest X-ray and 12-lead electrocardiogram are shown in the image 1a & 1b. Troponin I levels were measured at 59 ng/L (reference range: 10 – 23 ng/L), NT-pro BNP levels were noted at 6107 ng/L (reference range: 70 – 133 ng/L), and CRP levels were significantly elevated at 106.9 mg/L (reference range: 0 – 1 mg/L). The tropical fever workup was positive for scrub typhus, and she was started on intravenous doxycycline along with azithromycin.

|

Ques. Which of the following features does not point towards myocarditis?

|

ANSWER: Kindly check answer in the supplementary issue (link/doi of that issue CLICK HERE!

JASPI/Pearls/009/2025 |

Kashish, Prasan Kumar Panda*

Department of Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Uttarakhand, India

*Corresponding author: Dr. Prasan Kumar Panda, Department of Medicine (ID Division), All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, 249203, Uttarakhand, India

Email: prasan.med@aiimsrishikesh.edu.in

Copyright: © Author(s). This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Case Vignette A 51-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes and chronic HCV infection presented with a 3-month history of productive cough, fever, abdominal distension, and dyspnea. Evaluation revealed decompensated chronic liver disease (DCLD), Child-Pugh B (score 9) with high HCV viral load (7,12,000 IU/mL). Imaging showed bilateral pleural effusion and ascites, and sputum CBNAAT confirmed rifampicin-sensitive pulmonary tuberculosis.

Given her advanced liver dysfunction, initiating both anti-tubercular therapy (ATT) and direct-acting antivirals (DAA) posed a significant challenge. ATT (especially isoniazid and rifampicin) carries a high hepatotoxic risk, and the use of DAAs in decompensated cirrhosis also requires caution. Following stewardship principles, the team opted to initiate ATT first, with close monitoring of liver function, and defer DAA therapy until completion of the intensive TB phase or stabilization of hepatic parameters.

Ques. In a patient with decompensated chronic liver disease (Child-Pugh B) who has active TB and HCV co-infection, which of the following best describes the recommended approach to initiating therapy? A. Start ATT and DAA concurrently regardless of liver function. B. Initiate ATT first and delay DAA until liver function stabilizes (usually after the intensive phase of TB treatment). C. Begin DAA first to improve liver function before starting ATT. D. Defer both therapies until liver enzymes normalize completely. |

ANSWER: Kindly check answer in the supplementary issue (link/doi of that issue CLICK HERE!